The Second Amendment’s Irish Link

By William E. Devlin

Does the Second Amendment of the U.S. Constitution have an Irish connection?

The answer is a qualified yes.

The Second Amendment’s two clauses: “A well-regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the People to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed,” still spark intense debate about their meaning and extent.

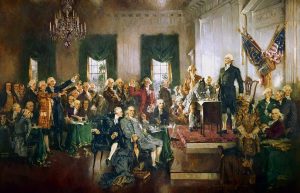

But like other parts of the Bill of Rights and the Constitution, the amendment owes its wording in part to an English antecedent. The Framers of the American Bill of Rights frequently turned for inspiration to a document they considered their birthright as Englishmen – the English Bill of Rights. That act was passed by Parliament in 1689 to prevent any future recurrence of what it saw as the tyrannical overreach of the Stuart kings.

The American Bill of Rights says, to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed 1689 English Bill of Rights states that subjects which are Protestants may have arms for their defence suitable to their conditions and as allowed by law

There is a right to bear arms in that document as well, but it’s stated differently: “That the subjects which are Protestants may have arms for their defence suitable to their conditions and as allowed by law.” A list of grievances that precedes it spells out its necessity: “By causing several good subjects being Protestants to be disarmed at the same time when papists were both armed and employed contrary to law;”

So how does this relate to Ireland?

James II and Richard Talbot, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

The guarantee of arms for Protestants can be traced to certain actions of the last two Stuart kings of England. The covertly pro-Catholic English King Charles II, who died in 1685, and the openly Catholic James II who succeeded him, had authority through the Militia Act of 1662 to disarm “persons dangerous to the peace of the kingdom.”

James II used it liberally to disarm potential enemies, particularly after a short-lived rebellion in the west of England greeted his new reign in 1685.

But James II also began to wield this authority to carry out his agenda of restoring Catholicism to his realm. He did this by disarming Protestants in the officer corps of militias throughout his realm and replacing them with Catholics. Nowhere was this initiative carried out more completely than in English-occupied Ireland, thanks to Richard Talbot, Earl of Tyrconnell.

The English Bill of Rights has its origins in the ‘Glorious Revolution, by which the Protestant William of Orange Overthrew the Catholic James II.

Talbot, born in the province of Leinster about 1630 into an old Anglo-Norman Catholic family and thus part of the “Old English” segment of landowning gentry in Ireland, led a colorful life. An ardent supporter of the Stuarts, he fought on their side as a young man in the civil wars of the 1640s and 50s.

Talbot fought as a cavalryman and was captured three times, first by Parliamentary commander Michael Jones at the Battle of Dungan’s Hill in 1647, then at Drogheda where the above-described incident took place, then in the subsequent ‘tory war’.[1] He escaped the besieged town of Drogheda just before Cromwell’s Parliamentary forces massacred its garrison. At one point Talbot was captured and interrogated by Oliver Cromwell himself before being ransomed.

“Old English” Catholic landowning families like his had lost whatever Irish lands they had during Cromwell’s and prior confiscations. Talbot’s ultimate aim was the restoration of his class and their lands. However, our understanding of him is colored by the fact that almost every account seems to have been written by someone who despised him. Even his secretary, Thomas Sheridan, described him as “a cunning dissembling courtier…turning with every wind to bring about his ambitious ends.” Like some U.S. politicians, he was tagged by his contemporaries with unflattering nicknames that included “Lying Dick,” “Mad Dick,” and “Fighting Dick.”

Talbot maneuvered behind the scenes at the Stuart courts for years, finally finding a willing patron in James II. In 1685 James made him Earl of Tyrconnell (the former O’Donnell territory in northwestern Ireland that makes up most of County Donegal). The following year James promoted him to Lord Lieutenant for Ireland, giving him control of the armed forces as well as political appointments.

The same year James authorized his lieutenants to search for guns held by persons hiding them “under pretense of shooting matches.” [2] Seizing the opportunity to re-establish the control once held by his class and with an eye to possibly create a semi-independent Irish state under a Catholic king, Talbot moved swiftly to re-shape the judiciary and the rest of officialdom, but zeroed in especially on the armed forces.

Disarming the Protestants of Ireland

James appointed the Catholic Richard Talbot Earl of Tyrconnell as his Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. He set about disarming Protestants and filled the army with Catholics.

Using as a justification the Argyle revolt in Scotland in 1685, he began an aggressive campaign of disbanding Protestant militia units and replacing them wholesale with Catholics. According to historian John Childs in his book “The Army, James II and the Glorious Revolution,” recruiters went to church festivals and fairs. In mid-1685, at the time of Talbot’s appointment, Ireland’s 8200-strong army had been virtually all-Protestant, especially the officer corps. By six months later, 1150 men had lost their places. 350 members of the Irish Foot Guards were disbanded in one day.

Talbot/Tyrconnell quickly used his authority to fill new officer commissions with sympathetic Catholics. By mid-1686 the Irish military force, the primary purpose of which was to protect the occupying English Protestant population and their property interests, was comprised of two-thirds Roman Catholics, along with almost a third of its commissioned officers. Most of the new officers were Old English Catholics, but the non-commissioned recruits were native Irish, or “O’s and Macs.” [3]

Being Irish history, of course there is a song about all this. “Lilliburlero” appeared around the time of the English Civil War of the 1640s but was re-written with new lyrics in Talbot’s time to parody him. Without its refrains, the song’s opening lines go:

Ho brother Teague, dost hear de decree?

Dat we shall have a new deputie,

Oh by my soul it is a Talbot

And he will cut every Englishman’s throat

Now Tyrconnell is come ashore

And we shall have commissions galore

And everyone that won’t go to Mass

He will be turned out to look like an ass

Now the heretics all go down

By Christ and St Patrick’s the nation’s our own

‘Teague’ is a corruption of the Irish first name ‘Tadgh’ representing a native Irishmen or, more generally, an Irish Catholic. The song expresses the fear that Catholics will use their commissions as officers to ‘cut every Englishman’s throat’ and to force Protestant to ‘go to Mass’.

There is no question that Talbot/Tyrconnell’s actions horrified the English. In parliamentary debates the Irish example was cited more than once as a nightmare scenario which could easily be duplicated in England under the authority of the Militia Act. Sergeant John Maynard declared that “…an act of Parliament was made to disarm all Englishmen, whom the (king’s) lieutenant should suspect…this was done in Ireland for the sake of putting arms into Irish hands.” Sir Richard Temple called it “the power to disarm all England – now done in Ireland.” [4]

The nineteenth century English historian Thomas Macaulay summed up the English view of this period, writing that “Although the country was infested by predatory bands, a Protestant gentleman could scarcely obtain permission to keep a brace of pistols.” [5]

Tyrconnell’s rebuilt army, stocked with newly-recruited Catholics in both the officer corps and the ranks, would become a critical factor in holding Ireland for James II when he was finally challenged by William of Orange, Parliament’s favorite to replace him in what became known as the Glorious Revolution.

War and ‘Glorious Revolution’

William landed in England with over 40,000 Dutch troops in October 1688, causing James to panic and to flee to France. William assumed the throne, with the approval of Parliament, claiming James had abdicated. William had taken power in England almost bloodlessly.

In Ireland, however war ensued. With the exception of the Battle of Newtownbutler and the siege of Derry, Tyrconnell’s forces inflicted defeat after defeat on Protestant Williamite forces early on in places like east Ulster and Cork until William began sending troops to Ireland, first under Schomberg in 1689, and then arriving himself in 1690 with a large Dutch and Danish force to enforce his succession.

Disarming of James’ Irish enemies did not stop the Irish Jacobites decisively losing the war with William of Orange.

With superior numbers and firepower, William was able to turn the tide against James’ Irish armies, comprised not only of Tyrconnell’s newly raised levies, but over 6,000 French regular troops contributed by French King Louis XIV. James’ forces now met defeat after defeat – notably at the battle of the Boyne, in 1690, after which James himself again sought refuge in France.

And, after successfully resisting in the first siege of Limerick in 1690, the Jacobites finally went down to defeat at the battle of Aughrim, and a second siege of Limerick in 1691. At the latter, Talbot/Tyrconnell himself died, possibly by poison, possibly of a burst ulcer, before the Jacobites’ final surrender.

William’s triumph quashed any dreams Catholic landowners had of recovering lost lands. The brutal Penal Laws imposed on the Catholic Irish in the wake of his victory turned the tables on Catholics, who now found themselves disarmed. Their homes could be broken into by magistrates to search for arms. Gunmakers were even forbidden to take on Catholic apprentices.[6]

The disarming of Catholics was aided by the mass exodus of Catholic Irish troops out of the country. When William of Orange first landed in Britain in 1688, three predominantly Catholic Irish regiments were sent to England to support James. But after James decided to flee to France and not to resist the Dutch expedition in England, these Irish regulars were left stranded there. They were disarmed and most ended up shipped to Austria to serve in the Habsburg Emperor’s army fighting the Turks. [7]

Furthermore, after the Jacobites surrendered at Limerick in 1691, over thirty thousand Catholic soldiers were transported to France under Patrick Sarsfield and drafted into French service, in an episode known as the ‘Flight of the Wild Geese.’

American Legacy

Eight decades later, when several of the rebellious American colonies began to draft new state Constitutions with Bills of Rights attached, and finally with the drafting of the Bill of Rights to the federal Constitution in 1791, the wording of the right to bear arms eliminated the reference to Protestants. Debates over wording and meaning at that time seemed rather to have revolved around militias as a backstop against the development of a powerful standing army, or about whether the right to bear arms was essentially an individual one.

The American constitution did not limit the right to bear arms to Protestants as Catholics were no threat there, but most blacks were excluded from citizenship and therefore from constitutional rights.

Those concerns, particularly the latter, have largely shaped the recent modern debates in the U.S. about gun control measures and the meaning of the Second Amendment. For the framers of the Constitution, the reference to a Protestant right to bear arms would have been redundant; all of the thirteen original colonies were overwhelmingly Protestant (although different denominations filled the role of established church in different regions), most had instituted requirements for militia service since their founding to defend against Indian, French and pirate attack; and the tiny number of Catholics, Jews and others among them posed no threat.

To them the potential threat of a large armed minority in their midst would have been the large number of African slaves and smaller number of free blacks, mostly in the Southern states, who in any case were excluded from citizenship and most other civil rights that went with it until passage of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1868, after the American Civil War. Until then, access to arms by blacks was restricted by laws and court decisions in different states. Thus there is a parallel here to the status of the Irish in Penal Law Ireland and that of slaves and free blacks in America.

This historical step on the road to the U.S. Second Amendment may be largely forgotten, but when one side of the gun control debate in America turns its rhetoric to “resisting tyranny” and “the government coming to take your guns,” it’s surely evoking the legacy if not the rhetoric of Protestant resistance to Richard Talbot and James II in seventeenth century Ireland.

References

[1] You can read some more details here for further info and listen to Padraig Lenihan discuss Talbot here.

[2] (2 Calendar of State Papers (Domestic), James II, No. 1212 at p. 314 (December, 1686), quoted in: Hardy, David, Historical Bases of the Right to Keep and Bear Arms. Originally published as Report of the Subcommittee on the Constitution of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, 97th Cong., 2d Sess., The Right to Keep and Bear Arms, 45-67 (1982) (“Other Views”). Reproduced in the 1982 Senate Report, pg. 45-67.]

[3] John Childs, The Army, James II and the Glorious Revolution,, p. 61

[4] 2 Philip, Earl of Hardwicke, Miscellaneous State Papers From 1501-1726, at 407-417 (London, 1778, quoted in Hardy, op cit.).

[5] (3 Thomas Macaulay, The History of England in the Accession of Charles II, 136-37 (London, 1856), quoted in Hardy, op. cit.)

[6] https://www.libraryireland.com/JoyceHistory/Penal.php

[7] Padraig Lenihan, Consolidating Conquest, Ireland1603-1727, p.175.