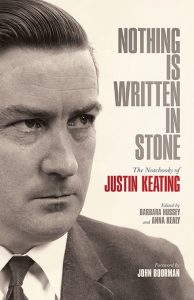

Book Review: Nothing is Written in Stone: The Notebooks of Justin Keating.

Edited by Barbara Hussey and Anna Kealy.

Edited by Barbara Hussey and Anna Kealy.

The Lilliput Press 2017.

Reviewer: Barry Sheppard

I think it is fair to say that to the casual reader of Irish history that Justin Keating is not a name which stands out as worthy of note in the plethora of twentieth century figures which shaped the nation. Indeed, his impact was not as dramatic as many who occupy the shelves of both general and specialist outlets in history.

He didn’t participate in war, he didn’t die young in the glory of battle or assassination, nor was he at the forefront of many major political battles which have defined so many in our history.

Keating’s book, not unlike a lot of memoirs of those in the public eye, are a chance to ‘set the record straight’, sometimes coming as this one does, posthumously. The problem this kind of tome poses for the historian therefore is how much historical value is it worth? Memoirs of political figures are invariably strongly biased towards their own political viewpoint, and the inaccuracy of personal memory is an ever-present problem. Indeed, Keating himself concedes at the outset that he was often described as an ‘opinionated little git’.

Justin Keating was a long time Labour Party politician and in his own words ‘an opinionated little git’

He freely acknowledges that he retained poor documentation of his life and that the book offers no new revelations. Further to this, Keating claims that the recital of his daily life would be of not much interest to anyone, even himself. It therefor begs the question, why then should the public want to read of his exploits?

Well, for this reviewer, it is the time period in question more-so than the author which held the attention when the assignment was offered. Keating was born into an Ireland still raw from the ravages of revolution and in a time when religiosity was ever-increasing and fusing with ideas of national identity. From his formative years in the early 1930s, through to his death on New Year’s Eve 2009, Keating witnessed a massive number of changes in Irish society. The chance to read the testimony of a life in public office which spanned these decades of change was something the reviewer could not pass up.

However, Keating’s opening statement that records related to his life were poorly kept, colours the experience and leaves the reader wondering what is the truth and what, if anything has been exaggerated to make a life seem more windswept and interesting when coming from the pen of a man nearing the end of his days.

There has been some academic input into the project, a number of archivists and academics have helped with primary material to bolster the manuscript, most notably from historian David Dickinson. Nevertheless, the work is a personal testimony rather than a work of historical record and the reader should not lose sight of this.

Early Life

Keating’s early home life and schooling reads like a novel. Descriptions of his rural Irish upbringing, with milking cows, mountains, poor quality land and frequent trips to the Arran Islands are strangely reminiscent of the memoirs of the post-Celtic Twilight islanders of Sayers, Ó Súilleabháin, and Ó Criomhthain, popular representations of a culture which Keating deromanticises as a decaying ‘dependency culture’ infected with ‘racist Celtic nationalism’.[1]

Keating is scathing about Irish ‘racist Celtic nationalism; and ‘dependency culture’.

Keating’s assessment of the cure for this Celtic dependency culture in Ireland has not aged well since he penned his memoirs in the mid 2000s. He stated: ‘I hate those gestures of pretended servitude, and I am very pleased to say that the Irish are coming of age and gaining some self-respect. Success is the best cure, the ‘Celtic Tiger (I hate that racist term) is healing us’.[2]

Keating’s description of an idyllic, if poor-ish life in 1930s Ireland is all too familiar to those with a knowledge of either twentieth century Irish history or contemporary Irish literature, and like so many recollections of the period the ‘shadow of the gunman’ isn’t too far away from the surface of a seemingly innocent and tranquil rural society. Arms dumps, and family connections to veterans of recent conflicts were daily reminders of political and territorial issues which weren’t quite settled.

The IRA murder of a neighbour, family friend, and local Detective Sergeant in Special Branch, Denis ‘Dinny’ O’Brien in 1942 had a profound impact on Keating and cemented his hatred of paramilitarism of all descriptions.

Keating’s hatred of political violence was not confined to Ireland’s troubles, however. He recounts on his honeymoon in 1953 that while in France, celebrating the anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July that he witnessed the killing of six Algerians by French police. This he said brought back troubled memories of O’Brien’s murder and cemented his detestation of physical force in the pursuit of political aims.[3] He did not, however comment on the irony of at the time taking part in the celebration of an act of revolution in which some ninety-nine people had lost their lives in political violence in one afternoon.

His political awakenings, influenced by his mother, in political and Bohemian Dublin circles are very interesting. His mother’s knowledge of iconic political figures such as Rosa Luxemburg, and closer to home, that of Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, not forgetting his parents stance on the Spanish Civil War provide an appealing insight on the ideological battles fought in Irish homes in the 1930s on the various viewpoints of the Spanish conflict.

The staunch support of the then powerful Irish Catholic hierarchy for the ‘upstart dictator’ Franco seemed to be Keating’s biggest awakening, both in terms of his political leanings and his distaste for religion and its influence in Irish public life.[4]

Catholic Church

A major theme of this work which stems from the stance of the Church on the Spanish Civil War, is the impact the Catholic Church had on Irish education, as well as healthcare and the control over generations of disadvantaged youths. Keating is scathing of the monumental abuse the Catholic Church oversaw, and the financial profiteering from ‘the ill-treatment of their unfortunate and mostly blameless charges’.

Aspects of the Catholic education system, especially the ‘reform schools’ ‘infuriated’ Keating.

The attack of a man well into his seventh decade at the time of writing is passionate and impossible not to side with. His anger at the cruelty, violence, and sexually-inspired beatings which he states have ‘long categorised Irish education’ and the infuriation at a system of reformatories which ‘churned out angry, antisocial kids who spent a lifetime in conflict with society’, clearly come from a man who valued, above all, educating young minds.[5] Almost ten years after his own death the words in this particular passage are bursting with life.

His take on the problems within all levels of the Irish education system are noteworthy and display many ideological battles, from cultural to religious and philosophical. His assessment of the thorny issue of the Irish language in Irish education, particularly the counterproductive methods of forcing the language down the throats of school children, especially in the mid decades of the twentieth century are reminiscent of themes explored in Donald Akenson’s A Mirror to Kathleen’s Face: Education in Independent Ireland 1922-60.[6]

A much more interesting, and less discussed aspect of Irish education history arises during his time as a student at UCD, studying the biological sciences. The complete omission of Darwinian Theory from third level education shocked Keating, and showed just how far Ireland lay behind in terms of scientific educational advancement. He credits Darwin and Marx as major figures in his intellectual development.

Throughout the book Keating takes pot shots at Irish sacred cows. The Irish Catholic Church bearing the brunt of his ire. Other targets include political and cultural nationalism, sectarianism, certain politicians, and that once sacred icon in Ireland, Mother Teresa: ‘I think she is a phoney, more concerned with snatching souls than with saving bodies’.[7]

Politics

The later chapters which cover his political career are focused on the home and European fronts. His first major political battle in front line politics, the 1972 European Referendum is interesting given the blanket coverage for the past eighteen months of Brexit. Campaigning for the No side he travelled the country setting out his case. During campaigning he developed a firm friendship with Garret Fitzgerald. Keating’s assessment of Fitzgerald is what we’ve come to expect from political recollections, a man who was well informed, fair, and courteous.

Keating rubbed shoulders with the giants of late twentieth century Irish politics Garret Fitzgerald, Charles Haughey and Conor Cruise O’Brien.

Equally unsurprising is his appraisal of one Charles James Haughey. Wildly ambitious, with an intense hunger for the goodies of the nouveaux rich, it is hardly revelatory. Nevertheless, it is during the passages on Northern Ireland and the Arms Crisis of 1970 that we see what Keating really thought of ‘the Boss’.

Although he didn’t think Haughey was directly involved, he did accuse him of opportunistically sitting on the fence, non-committal to the Blaney/Boland camp, waiting to see if he could use the mess to his own political advantage and unsettle his long-term target, Jack Lynch. Haughey’s dismissal saw him begin the long pilgrimage back into power and into the nation’s affections: ‘ultimately, all was forgiven, leading Fianna Fáil from the Taoiseach’s chair. The Irish people love a rogue’.[8]

His sympathy for the people of the north (dismissing easily applied terminology such as ‘tribal’) and understanding of the complexity of the conflict, shows a empathetic politician who saw the need for give and take on all sides (although he was at times scathing of the British establishment). Reconciliation seemed to be his watchword to the end.

Besides Fitzgerald, a number of other politicians made the list of the admired. Paddy Hillery, Brendan Corish, and Noel Browne were all figures held in high regard. Undoubtedly the most complicated political relationship of his life was with Conor Cruise-O’Brien, who he first encountered in 1939 and would end up in Government with in thirty years later. Keating’s mother had been the secretary of the Cruiser’s aunt, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington. Initially in awe of him, they became quite close family friends, before political differences wedged them apart.

Cruise-O’Brien’s dislike of John Hume was one particular sticking point, while the publication of his book States of Ireland proved to be the point of ideological departure between the two. Keating spoke of the seriousness of Cruise-O’Brien’s viewpoint: ‘I believe that Conor has done great harm to the broad policy of sincere reconciliation of both communities and has, against his own wishes, borne great aid to the IRA’.[9]

The remainder of the book sees Keating wrestle with the familiar subjects of the church, religion, atheism, globalisation, war and the military. No doubt his views are interesting, but they won’t sway anyone’s political leanings. I don’t believe they are meant to.

Throughout the book, from his upbringing, the social circles his parents inhabited to his time as a politician, one gets a real sense of just how small the circles of the political and cultural elite in Ireland have been. One is left with the opinion that they have always been a breed apart. For all of Keating’s genuine concern for his fellow man and woman, he at times seems part of that elite society which replaced the previous elite in 1922. That is not a slight on the memory of the man, but a comment on the society which he was born into.

The evolution of Keating’s political journey is, well, it is the main theme of this book and takes the reader on an interesting voyage. The influence of his parents, particularly his mother, the Spanish Civil War, witnessing shocking acts of violence, education, his brief broadcasting career, political battles and campaigns, Europe, Northern Ireland, the environment, and global concerns, have all contributed to a fairly fluid left of centre political journey.

As Keating himself pointed out at the beginning, there were no revelations to be had. At times it reads like a novel, at other times it is clear his intended audience was himself. Despite the admission that poor documentation had been retained and the apprehension that it will be of little value to the historian, the book is engaging, and the author comes across as genuine. There are valuable passages within, which the historian can find useful. Nevertheless, it is no substitute for proper history.

References

[1] Justin Keating, Nothing is Written in Stone, p.15

[2] Ibid, p. 16.

[3] Keating, Nothing is Set in Stone, p. 52.

[4] For an example of the impact the Spanish Civil War had on Irish daily life see Fearghal McGarry ‘Irish Newspapers and the Spanish Civil War in Irish Historical Studies Volume 33, Issue 129

May 2002 , pp. 68-90

[5] Keating, pp 37-39

[6] Donald Akenson, A Mirror to Kathleen’s Face: Education in Independent Ireland, 1922-60 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1975)

[7] Keating, p. 64.

[8] Keating, p. 139.

[9] Keating, p. 133.