The Battle at South Dublin Union, 1916

The battle at South Dublin Union was some of the most close-quarters and brutal fighting of Easter Week. By John Dorney

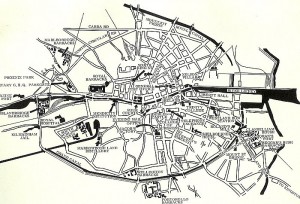

The South Dublin Union was a sprawling 50 acre site, where St James Hospital stands today, in the south west of Dublin city.

In 1916 it was a complex of workhouses and hospitals for the ‘destitute, infirm and insane’ and had over 3,200 inmates. At a time when 90% of Dublin’s working class could expect to end their days destitute, it was a vital public service. [1]

The Irish Volunteers Fourth Battalion occupied the South Dublin Union on the first day of the Rising.

Unknown to any of the inmates or to the staff at the SDU it had been chosen that Easter Monday, as one of the sites the insurgent Irish Volunteers would take over

The occupation

The Irish Volunteer 4th Dublin Battalion had mobilised at Emerald Square in Dolphins Barn. Eamon Ceannt, a gruff, but dynamic man was in command seconded by Cathal Brugha.

Also present were officers William T Cosgrave and Con Colbert. Due to the confusion the previous day over Eoin MacNeill’s countermanding order – which nearly called off the Rising, there were fewer men than they would have liked, about 150 in all.

Their job was to take over the south west of Dublin city and to head off anticipated attacks from the British Army barracks there into the city centre. Men were deposited at Roe’s Distillery, Jameson’s Distillery under Colbert and Watkins Brewery on the southern edge of the SDU complex, while the majority of the battalion, about 65 men, followed Ceannt into the complex itself.

Patrick Smyth was the ward master (a kind of general manager) in the Union. He recalled that at about midday, Volunteers under Ceannt and Cosgrave, both of whom he knew personally, marched into the main gate and began to barricade it.

‘They immediately took over the buildings known as the board room and clerks offices and also a department called the orchard sheds and the Nurses home where Ceannt remained in command. No word was spoken to me’. [2]

Annie Manion was a Matron there. She remembered a terrible panic and sense of bewilderment among staff and patients. A maid Rachel Blundell, ‘a very religious old soul’ told her that a group of Volunteers had come to the house and hammered at the door. ‘She was so frightened she looked out the window and said she could not open the door because there was nobody there but herself, so they ordered her to open the door in the name of the Irish Republic’. She opened the door and a crowd of Volunteers came in and took possession.’

The South Dublin Union was a sprawling complex of hospitals and workhouses.

‘I heard also that on Monday another group of Volunteers came in by the James’s Street gate, went straight over to the Nurses’ Home and occupied it. They were headed, I understand, by Cosgrave. Most of the nurses were in bed because they had been on night duty. They got very little time to get up, gather as many of their belongings as they could, and clear out. On Tuesday we were in a state of panic. We did not really know what we were doing’.[3]

Inside the SDU the Volunteers experienced little difficulty in taking over the buildings but the complex was so vast they could only hold a few of them – principally the Nurses’ Home and initially, the Female Chronic Hospital, the Protestant Hospital, and the Acute Hospital.

Nearby though, at Roe’s Distillery the occupation provoked a near riot with the local civilians. Volunteer Thomas McCarthy recalled ‘During the time we were trying to knock down the gate we were practically attacked by the rabble in Bow Lane, and I will never forget it as long as I live. “Leave down your —- rifles,” they shouted, “and we’ll beat the —- out of you.” They were most menacing to our lads.’[4] Others recalled having to defend themselves with rifle butts from the wives of men serving in the British Army.[5]

British Response

The British troops from close-by Richmond Barracks – in fact largely Irishmen from the Royal Irish Regiment – quickly launched a counter attack. At first, in anticipation of a riot rather than a gun battle, they marched in formation to the James’s Street entrance of the Union with bayonets fixed but rifles unloaded. Three were hit in the first volley from the Volunteers, causing the rest to scramble for cover.[6]

The first British troops to attack the insurgent positions in the SDU were Irishmen of the Royal Irish Regiment.

Confused close quarter fighting ensued, sometimes hand to hand, in and around the hospitals and dormitories. A number of patients as well as Nurse, Margaret Keogh were killed, along with a British officer, who was shot dead as he peeped over a wall.[7]

James Kenny, a Volunteer recalled that more British soldiers had entered from the Rialto gate and soon his position was under intense fire.

‘We fought them and Dan [McCarthy] was badly wounded, in the scrap. I threw myself flat on the ground when I saw Dan fall and faced four soldiers on my own. When they saw me take aim with my rifle from my prone position they cleared off round the corner. The soldiers in question belonged to the Royal Irish Rifles and were just back from France’. [8]

The Volunteers had to abandon most of their positions and retreat to the Nurses’ Home – a strong three storey building. Kenny himself was hit in the firing as was Volunteer Lieutenant Douglas Ffrench Mullen. A Volunteer named Burke was shot dead that night as he tried to light a cigarette from another Volunteer, Fogarty’s pipe. Fogarty, wracked by guilt became ‘mentally deranged’ and had to be disarmed and kept under watch for the rest of the week. [9] At Roe’s Distillerry, Thomas McCarthy, the Volunteer officer, ran out of food and ammunition and ordered his men to go home.[10]

The British initial assault was however called off when orders from General Lowe reached the Royal Irish Regiment that they were to return to barracks. They had lost at least six dead and more wounded. The combat was particularly distressing for soldiers who were supposed to be convalescing from the Western Front. It was intense, short range fighting and for some of them it was too much.

Patrick Smyth the ward master, who was trying to keep the supply of bread to the patients and inmates going came upon a soldier standing over the body of one of his comrades, who was pointing a rifle at him. ‘The rifle man was shaking all over ‘.

Smyth found another soldier badly wounded, lying in the yard and another at the dining hall ‘was talking to some inmates when he was shot’. According to Smyth, one soldier in no mood for heroics, managed to get himself evacuated from the fight in a coffin alongside a dead comrade.[11]

Close Quarter battle at the Nurses’ Home

For most of the Tuesday and Wednesday, however, little happened at the SDU. The British General Lowe instead decided to bypass the position, first clearing out the Mendicity Institute after a bitter fight and then securing a line of communications down the south quays into the city centre.

On the Thursday, British troops launched a determined attack on the Nurses home. They were beaten off after ferocious close quarter fighting inside the building.

The Volunteers at the Nurse’s Home hardly saw a British soldier for two days and busied themselves fortifying the building.

On the Thursday however the British brought up reinforcements, two companies of the Sherwood Forester regiment, some other units from the Curragh and some RIC armed policemen. There was heavy fighting around the Marrowbone Lane Distillery.

Volunteer Robert Holland was put in a top floor room with a Cumann na mBan woman, who loaded his two rifles while he fired. By Thursday evening he, “could see quite a lot of [British soldiers’] bodies all around outside the wall and as far as Dolphins Barn Bridge. I could just see a pit and Red Cross men working at it putting bodies into it”.[12]

The most harrowing combat of all though came when the British troops assaulted the Nurses Homes inside the SDU. They gained access by blowing a hole in the wall, but found the inside of the building barricaded. This was room by room fighting, mostly with hand guns and grenades (the British had Mills bombs and the Volunteers improvised canisters on which a fuse had to be lit before throwing).

Cathal Brugha was badly wounded by a grenade blast and left for dead by his comrades. They came back when they heard him singing deliriously and dragged him into the kitchen where his wounds were treated.

The duel with grenades went on for most of the day. In one instance a Volunteer kicked back a bomb towards the British before it could explode. Eamon Ceannt shot an RIC man at point blank range with his revolver when tried to force his way through a door. Another soldier was shot dead when he poked his head through a hole the other troops had hacked in the wall. At 8 that evening the British called off the assault.[13]

The fighting on the Thursday had been ferocious but as Jim Kenny recalled; ‘Thursday’s hard fighting finished at dark and was not resumed. We remained on guard at our posts until Sunday morning.’ [14]

The Royal Irish Rifles lost three men killed at the SDU on the Thursday and the Sherwood Foresters lost three killed and seven wounded. Along with one RIC constable, that brings the known British casualties at the Union to 13 dead and more wounded. At and around Marrowbone Lane, there were more British casualties from a mixture of units, bring the British forces’ death toll around the South Dublin Union up to more than 20 , with at least twice that number wounded.[15]

The Republican roll of honour lists seven Volunteers killed in action at the SDU, all killed on the first day of fighting, Monday the 24th.[16] At least four civilians died within the walls of the SDU and more were killed in the firing on the streets outside, including, according to the Irish Times, two children at Dolphin’s Barn.

The SDU itself was not badly damaged in the fighting, however due to the fact that artillery was not used.

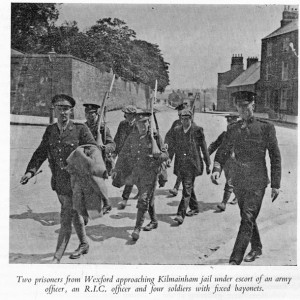

Surrender

All was more or less quiet at the SDU from Thursday evening until Sunday when word of Pearse’s surrender at Moore Street came to reach the rebel garrisons there. Nurse Elizabeth O’Farrell, accompanied by a priest, ‘Father Aloysius’, volunteered to bring the news to the Volunteers around the city.

At about 10 o’clock on Sunday morning Father Aloysius in company with three British officers and Thomas McDonagh from the Volunteer garrison at Jacobs came to deliver the terms. Ceannt was dismayed and did not want to surrender.

Similarly at the Jameson Distillery on Marrowbone lane, full with over 100 Volunteers and Cumann na mBan women, the rebels were convinced they were winning and had organized a victory ceilidhe (Irish dancing) for that night.[17]

The Volunteers in the South Dublin Union were shocked when they received orders to surrender. Many had though they were winning.

Patrick Smyth, the ward master who had remained in the SDU throughout the battle, tells of the surrender.

The British Officer proceeded to inspect the men [who had surrendered]… Cathal Brugha, who was wounded, was sitting on the foot-path. Ceannt remained where he was at the gate and conversed with me . I asked him his terms; he said they were unconditional. I said “that speaks very badly” and the words he used were “shooting for all us fellows and deportation for the Rank and file”. By that time the men were moving out the front gate . I shook hands with Ceannt and that was the last I saw of him.[18]

After the fighting had ceased, the local poor ransacked the buildings in an orgy of looting. The workhouse at the SDU was, within weeks, full of new inmates who had been made homeless by the fighting of Easter Week. [19]

Ceannt was right when he told Smyth he would be shot. He was executed on May 8th 1916, a week after his surrender. William Cosgrave was sentenced to death but reprieved. He went on to serve as the head of the first Free State government from August 1922.

Cathal Brugha escaped execution in 1916 due to his being too badly wounded to be tried. He was later killed in the first week of the Irish Civil War in July 1922.

References

[1] Michael Foy, Brian Barton, The Easter Rising, p131, Padraig Yeates, A City in Wartime p102

[2] Patrick Smyth Ward Master BMH WS 305

[3] Annie Mannion BMH WS 297

[4] Thomas MacCarthy BMH WS

[5] Fearghal MGarry, The Rising, Easter 1916, p143

[6] Neil Richardson, According to their Lights, Irishmen in the British Army, Easter 1916., p28-29

[7] Foy, Barton, Easter Rising p132 The Volunteers claimed he was a major but was more likely to have been one of two RIR captains killed at the South Dublin Union that day. There were;

Capt Alfred Ernest Warmington RIR kia SDU 24/4/16 Capt Alan Livingstone Ramsay RIR kia SDU 24/4/16. Both were natives of Dublin.

[8] James Kenny WS BMH 174

[9] Foy, Barton, p135

[10] Richardson, According to their Lights, p138

[11] Patrick Smyth BMH

[12] Annie Ryan, Witnesses, Inside the Easter Rising p128-133

[13] Foy Barton, Easter Rising p 136-137 Kenny BMH

[14] Kenny BMH

[15] Paul O’Brien, Uncommon Valour the Battle for South Dublin Union 1916, p124, Robert Holland at South Dublin Union noted that British military dead lying around Rialto bridge were from at least ten different regiments, indicating around ten killed there. Charles Townshend, Easter 1916, p.203

[16] The Last Post, p92-93 They were; Vols, John Owens (Combe Dublin), Brendan Donnellan (Fianna of Loughrea, Galway), James Quinn, (Blackpitts Dublin), Richard O’Reilly, William McDowell (Merchants Quay Dublin), John Traynor (Kilmainham Dublin), W.F. Bourke, (James St. Dublin). All killed on 24/4/16 the Last Post also claims Margaret Keogh, but she was in fact a civilian nurse. They probably mistook her for a Cumann na mBan activist who was killed by the British Army in 1921.

[17] Townsend, Easter 1916 p250

[18] Smyth BMH

[19] Foy, Barton, p139, Irish Times, May 11,1916