Frank Moss – A Forgotten Labour Leader of 1913

Christopher Lee on Frank Moss, the leader of the Swords strikers in the Lockout of 1913. See also Christopher’s articles on the strike in Finglas and Swords.

A century after the events of 1913 the names most closely associated with the Dublin Lockout are of course those of James Larkin, James Connolly and William Martin Murphy. The names of those persons killed or injured during the Lockout are also remembered, such as James Nolan, John Byrne, Alice Brady, James Byrne and even Patrick Daly.

However, Frank Moss, a union organiser who played a major role in the County Dublin farm labourers’ dispute, was imprisoned twice, went on hunger strike twice and was force fed on both occasions, and was a founding member of the Irish Citizen Army, has been forgotten.

During the height of the Lockout, Moss was the subject of speeches by Francis Sheehy-Skeffington and James Connolly, who referred to him as a ‘rough diamond’. Moss would appear in public standing beside the most recognisable names of Irish labour history, such as Larkin, Connolly, Countess Makievicz, William Partridge, Patrick T. Daly and Walter Carpenter.

Moss’ story provides an example of the treatment by the authorities of the lower ranked members of the Irish Transport &General Workers Union. Moss was singled out as the ‘ringleader’ of the strikers in Swords and imprisoned on the basis of farcical charges by courts presided over by land owners and farmers. Where others had been released from prison after only a few dayson hunger strike, Moss was brutally force fed and served his entire sentence.

Unlike the well-known names mentioned above, Frank Moss’ life is not well documented and most of what is known of Moss’ life and activities relates to a period from mid-1913 to mid-1914. As a result there are large gaps in Moss’ story.

Early Life

Francis Moss was born 20th August, 1870 at Cushinstown, County Meath, son of George Moss and Julia McKeown[1]. In 1899, Moss was living in Dublin at 24 Constitution Hill. On 23rdApril, 1899,he married Mary Ellen Gleeson, of Prebend Street, at St. Paul’s, Arran Quay.

However, in July,1899, barely two months after his wedding, Moss was sentenced to three months in Kilmainham for the embezzlement of 10s from his employer.[2]The prison register records his address as 54 Lower Wellington Street and he was described as, 29 years old, labourer, 5’ 6” (167cm), 134lb (61kg) dark brown hair, balding on top, blue eyes and a fair complexion.

By the 1901 census, Moss and his wife were living in Howth, but by 1903,Mosswas in trouble again. That year he served two terms in prison, both for smashingwindows.By now Moss’ fortunes seem to have sunk low as the prison registers record him as having no fixed abode and the whereabouts of his wifeis unknown.

Fascinatingly both prison registers for 1903 describe Moss as having no religion. Rather than the entry being blank, ‘nil’ is written, the only such entry on the pages. This may possibly indicate Moss was an atheist at the time. However, in later prison records, Moss’ religion is given as Roman Catholic, suggesting Moss either reconsidered his stance, or the officers chose to record the religion Moss was baptised, rather than his actual belief.

By the 1911 census,Moss is living in Swords but by now his wife is no longer with him.

Union Organiser for Swords

Throughout the farm labourers strike and Dublin Lockout, Swords was a stronghold of the ITGWU in rural County Dublin,described as “…the principal rallying-ground for the Larkinites”[3]. Moss was the union organiser for the Swords district for the duration of the farm labourers’ dispute and Dublin Lockout.

He was responsible for the farm labourers of the Swords district being the most unionised,organised and belligerent of all the strikers outside Dublin City.

Moss was a man drawn from the ranks of the poor, working class, rural labourer. The qualities which marked him out from his peers seem to have been his forceful and impassioned speaking, a strong leadership and, at times, reputation as a ‘hard man’.

Moss’ involvement with the labour movement probably dates from around early to mid-1913when James Larkin and the ITGWU commenced a campaign to improve the pay and conditions of the County Dublin farm workers. Throughout June and July 1913, Larkin held mass meetings in Swords, Clondalkin, Lucan, Howth and Blanchardstown enrolling large numbers of farm labourers and transport workers into the union. The Swords branch of the ITGWU established its headquarters in a house in the main street of the village which the strikers christened “Liberty Hall” in emulation of the ITGWU headquarters in Dublin.

By 1913, Moss was 43 years old and had already lived a fairly rough life, but a life probably little different from many of his peers. He had been in trouble with the law, spent time in prison, had been homeless, had married and been separated and had worked as a labourer for all of his life. He did not have an imposing build and a newspaper covering his trial in October 1913 described him as“…a poor looking man.”[4] However, clearly Moss had some personal characteristics which must have marked him out as the leader of the local strikers.

Moss was a man drawn from the ranks of those he led and represented, a poor, working class, rural labourer. The qualities which marked him out from his peers seem to have been his forceful and impassioned speaking, a strong leadership and, at times, reputation as a ‘hard man’. In the few contemporary newspaper articles which preserve Frank Moss’ words it is clear he could articulate the socialist and syndicalist position of Larkin and Connolly and would use an upstairs window of the Swords “Liberty Hall” to address hundreds of strikers in the street below. [5]

An indication of Moss’ leadership can be seen in his marching at least 200 strikers, at a brisk pace around the Swords district, for six hours straight. [6] Moss was clearly able to motivate, organise and lead his men. On other occasions,Moss could be reserved, quietly spoken and reticent to discuss his experiences, not “…making the slightest fuss about his personal sufferings.”[7]

Following the decision on 12th September 1913 by the County Dublin Farmer’s Association to join William Martin Murphy’s ‘lockout’ of union members, the farm labourers were drawn into the labour conflict. Throughout September and October 1913 the Swords strikers, under the leadership of Moss, were engaged in violent clashes with police and there were a number of acts of violence and intimidation against ‘scabs’.[8][9]

The Swords strikers would frequently attend labour rallies in Dublin where, on one occasion, they were heavily involved in attacking police during the worst rioting since ‘Bloody Sunday’.[10][11]

A substantial police presence in Swords was used to put down an attempt by Moss to conduct a labour demonstration during the Swords monthly fair, a deliberately provocative act on the part of Moss, certain to lead to a violent confrontation with farmers attending the fair.[12]

The Swords Riot

(Image Courtesy of Come Here to Me website)

The increasingly aggressive tactics of Moss and the farm labourers culminated in the Swords riot. On the evening of Wednesday 9th October Frank Moss addressed a crowd of strikers and told them:

“….that they had been “keeping too quiet in Swords” and that he himself had been too quiet during the strike there. If he were sent to jail another man would be sent there to lead the strikers, and instead of two cartloads of food they would get ten.”[13]

The riot began later that evening following the arrest of a striker who had been part of a group trying to scatter a herd of cattle being driven through Swords to the Dublin markets. After a failed attempt to rescue the arrested man, around 100 strikers went on a rampage, stoning the police barracks and smashing the windows of shops that supported the farmers.[14][15] Only after the police had gathered substantial reinforcements were they able to end the riot with several baton charges, leaving many strikers and police seriously injured. [16]

Moss was injured in a riot in Swords in October 1913 and subsequently charged with breaking a shop window.

One of those injured was Frank Moss. At his trial in early 1914, for smashing a shop window during the riot, mention was made of “…the severe injuries sustained by him on the night of the baton charge.”[17] The extent of his injuries is unknown, only that they were severe enough to be considered a mitigating factor in sentencing four months later. Moss may just have been unlucky, injured in the melee, but it is also possible he was deliberately targeted for violence by the police, as the ‘ringleader’ of the local strikers, the key local ‘trouble maker’.

Farcical Charges

In October 1913 Moss was charged with three separate acts of intimidation and smashing a window during the riot in Swords.The charges and the trial demonstrate the farcical and prejudiced nature of the legal system which Moss and many other strikers found themselves facing.

One of the charges filed against Moss was intimidating a union member by spilling his drink.

At the commencement of the trial on 12th October at the Swords Courthouse, Moss’ defence requestedany of the magistrateswho had a personal interest in the progress of the farm labourers’ strike, should stand aside and take no part in the hearing. However, despite many of them being farmers and land owners, none of the magistrates stood aside and the defence could only lodge a formal protest.[18]

The first charge against Moss was the alleged intimidation of the publican of O’Connor’s pub in Swords. Moss had gone to O’Connor’s pub when it became known a ‘scab’ was drinking there. When the publican refused to ask the ‘scab’ to leave Moss said “…did he want a riot raised?” Moss ordered all union members to leave the pub. While thepublican was afraid his windows would be smashed no one actually threatened this.[19]Despite this Moss was found guilty.

The second, and by far the least credible charge of intimidation, was that on the same day as the previous charge he intimidated a union member, James Lawless, by spilling the man’s drink. Lawless had been drinking in Daly’s pub when Moss ordered all union members leave because ‘scabs’ were drinking there. When Lawless told Moss he would leave when he finished his drink, Moss took the pint of porter from him and spilled it, both men leaving together. Despite Lawless telling the court he had no problem with Moss spilling his drink, Moss was found guilty of intimidating him.[20]

On the basis of this flimsy evidence the magistrates described the intimidation as “…gross, palpable and premeditated...” and Moss was sentenced to one month’s imprisonment on each of the charges.[21]At this point Moss’ defence gave notice of appeal against the convictions and elected to have the final charge heard by a jury at the County Commission.[22]

At the County Commission on 23rd October it was alleged Moss had intimidated a union member who had returned to work as he was unable to support his family on strike pay.Moss and about twenty men went to the field in which he was working and demanded his union membership card and badge.

Later that afternoon Moss returned with a parade of about 200 people accompanied by a fife and drum band, the same group of strikers he would keep marching for six hours. As the crowd approached the field they booed and hissed him, Moss calling out “You cur!”.[23]A Sergeant, who had followed the procession from Swords with fifteen constables, cautioned Moss against his conduct and language. Moss replied that:

“If you were a general on the field of battle and some of your men deserted or turned traitors, would they not deserve to be shot? We are not going to shoot anyone, we are doing our work by peaceful picketing.”[24]

A different version of Moss’ speech was recorded by the Irish Independent:

“…they were the local army of the industrial war, and that they meant to obey orders of their general even if they were to get a bullet for it.When a speaker said that a “scab was a traitor and that a traitor in the British Army would be shot down like a dog”, the district inspector cautioned him that his language amounted to an incitement to murder, and was being recorded by the police, whereupon an explanation was given that the words referred to were intended only to show that, although the men engaged in the industrial war were more powerful and more courageous than the British Army, they were more merciful than the later, and did not shoot traitors, but only booed them and enabled them to work with musical accompaniment, which they could avoid if they disliked it by giving up their work.”[25]

Though this passage can provide little more than a brief glimpse of Frank Moss it can give us suggestive hints. It is clear Moss was articulate and was well versed in the language of Larkin, Connolly and The Irish Worker and suggests he could be a commanding and rousing speaker.

Returning to the conclusion of the trial, one of the men who had accompanied Moss to the field told the court it was he who asked Smith for his union card and badge, not Moss. Despite this, Moss was found guilty and sentenced to three months in prison.

It would seem the Swords authorities had decided to rid themselves of someone they likely regarded as the driving force behind the farm labourers’ strike. To that end, Moss was sent to court on ludicrous charges and found guilty in courts administered by land owners and farmers, all to ensure his removal from the area, no doubt in the hopes the strike would soon collapse without his motivating presence. Taken in the context of Moss as a target of police violence during the riot in Swords, the moves by the courts to imprison him give the impression of an orchestrated campaign to incarcerate, intimidate and silence the Swords strike leader.

Imprisonment and Hunger Strikes

Moss was imprisoned in Mountjoy Gaol on 24th October 1913 and immediately began a hunger strike. The hunger strike tactic had, of course, already been used extensively by the suffragist movement both in Britain and Ireland and would later be adopted by the Irish nationalist and Republican movements. At the time of the Lockout the “Prisoner’s Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health Act”, also known as the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’ was in place which allowed for prisoners on hunger strike to be temporarily released if their life was in danger. However, once their health recovered, they were liable to be rearrested to serve the remainder of their sentence.

Moss went on hunger strike to force his release but was force fed by prison authorities

Prior to Moss’ imprisonment in October 1913, hunger strikes had already been used in connection with the Lockout by James Connolly and James Byrne, both being released after several days rather than being force fed.[26](See note below)

There was considerable outrage within the labour movement when it became known Moss was being forcibly fed. The image circulated was of Moss being inhumanly treated, carried to the feeding chair, strapped down, head held by brutal prison guards, a tube forced down his nose, or his jaws pried open, his throat held until blood came from his eyes, of vomiting and coughing up blood.[27]

James Connolly addressing a demonstration at Beresford Place called for the release of:

“…all the men, women and girls who still remain in Mountjoy in connection with the strike.” “One of those prisoners, Frank Moss, a rough diamond, had been hunger striking for ten days. They would especially demand his release. Moss was being subjected to the brutality of forcible feeding.”[28]

Francis Sheehy-Skeffington made an impassioned speech which singled out the plight of Frank Moss and called upon the government to stop:

“…the torture of forcible feeding in prison in the case of Frank Moss. The present government was one that bullied the weak and cringed to the strong. They did not attempt to forcibly feed Mr. Connolly or Mr. Lansbury when these men were in jail, but they thought that Frank Moss was an unknown man with few friends, and, therefore, they selected him out for this treatment. They had it on reliable authority that Frank Moss had been spitting blood and suffering from haemorrhage of the lungs, and they demanded his release before he became a physical wreck and had to be released.”[29]

Connolly and Sheehy-Skeffingtonsaw in Moss’ case a clear demonstration of “….the class administration of the law…”[30]

James Connolly had been on a hunger strike from 7th September to 15th September, when he was ordered to be released.George Lansbury, an English ex-Labour MP, was sentenced to three months prison for sedition and incitement to violence, went on hunger strike and was released after three days. Moss, a working class union organiser, was treated very differently and was force-fed and served his entire sentence.

Moss on Hunger Strike

After two days on hunger strike Moss was moved to the prison hospital and was force fed. This continued until 3rd November, when Moss ceased his hunger strike and resumed eating. He was sent back to his cell on 8th November but recommenced a hunger strike on 10th November. He was re-admitted to the hospital and was again force fed until 27th November, when he again resumed eating. He was allowed to serve the remainder of his sentence in the prison hospital.[31]

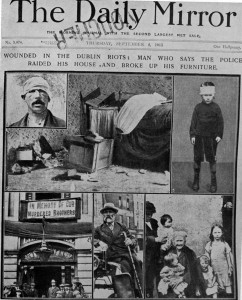

Following his release Moss was interviewed by the Daily Herald:

“Tortured in Prison

Today I heard from the lips of Frank Moss an account of the shocking tortures he endured while in prison. A silent man with an obvious reluctance to speak about himself or his sufferings, Moss told the story in a reserved and quiet fashion, that gave additional force to the horrors he spoke of. Frank Moss is the organiser of the Irish Transport Union for Swords, ten miles from Dublin, and has created an active organisation there among the agricultural labourers. Three charges of intimidation were trumped up against him, two of which are still hanging over his head. He has been told these will be dropped if he gives up his work for the Union, but that otherwise he may expect the full rigour of the law.

Not to be intimidated

Moss disregards this attempt to intimidate him, and since his release, ten days ago, he has been busy at his work in Swords, to which he quickly returned without making the slightest fuss about his personal sufferings. Sentenced on October 24th to three months hard labour, he began his hunger strike immediately on entering the prison. He had said nothing about his intention, and it was not till some time afterwards that his friends outside knew of his courageous action.”[32]

A report was prepared by the Mountjoy Prison Medical Officer to address the allegations raised in the Daily Herald article.[33] The report contested Moss’ claims of brutality and torture while being force fed. It states Moss seated himself on the chair and made no resistance as he was strapped in. When he refused to open his mouth the Medical Officer attempted to insert a feeding tube nasally but Moss moved his head to prevent it. His head was then held by two warders while the tube was inserted. The report went on to say that on all subsequent occasions Moss cooperated, voluntarily opened his mouth to admit the feeding tube and the straps where only used a few more times.[34]

While the report is comprehensive in refuting the allegations of brutality and ‘torture’, an official report would have been unlikely to substantiate them. However, the report also clearly indicates Moss was fed via a nasal tube only once, a fact that will become relevant during Moss’ second hunger strike and cast doubt on the entire report.

It is interesting to speculate upon Moss’ motivations for his ‘on again, off again’ hunger strike. Perhaps, realising early in his hunger strike that he was not going to be released, he decided to extract whatever concessions he could, engaging in his own version of ‘Cat and Mouse’ with the prison authorities. Once Moss was moved to the prison hospital he would have hadbetter conditions and food than in his cell.To that end,wheneverhe was moved back to his cellhe went back on hunger strike, ensuring he could remain in the hospital for the duration of his sentence.

During Moss’ interview with the Daily Herald he mentioned the two remaining charges of intimidation hanging over his head. His appeal against those convictions had been scheduled to take place while he was serving his three months sentence, but this was adjourned until early 1914.

Imprisoned Again and Second Hunger Strike

Moss was released from Mountjoy on 14th January, 1914, but despite already serving three months in prison, it seems the authorities were determined to continue pursuing Moss. He was in courtagain on 14th February 1914, charged with smashing a window during the Swords riot. Again, on the flimsiest of evidence, Moss was found guilty of smashing a window during the riot, and was sentenced to 14 days imprisonment.[35]

Sent back to Mountjoy, Moss immediately went on hunger strike. He remained on hunger strike until 17th February when he was forcibly fed via nasal tube. An article from the Daily Herald states he:

“…was strapped to the torture chair as before and forcibly fed. The process was excruciatingly painful, all the passages being still tender from previous insertions of the tube.”[36]

The report by the Mountjoy Medical Officer had previously stated Moss had been fed nasally only once, nearly three months prior. Judging by the pain Moss apparently experienced this was clearly not the case, undermining the credibility of the entire report.

Presumably due to the pain, no further attempt was made to force feed Moss until 20th February. Clearly Moss was not compliantly opening his mouth:

“This time the doctor had the utmost difficulty in getting the tube up his nose, and finally lost his temper.

Moss, describing his sensations under this torture, said, “he seemed to feel something snap in his head.” When he was brought back to his cell the agony in his head continued, and he felt as if his brain was going. “I did not mind dying” said Moss to me, “but I wanted to die sane.”

“For the rest of his stay in Mountjoy he took bread and tea twice daily, but as he was still manifestly ill he was released unconditionally yesterday”… During his imprisonment Moss was kept in the basement of the prison where, as a rule, prisoners are kept only one night. His cell was cold and draughty, and he contracted deafness in booth ears.

He complained of this repeatedly, but only on the last day was any heed paid to him. Then his ears were syringed and some relief given, but he is still suffering from deafness… Moss declared that the prison service is full of members of the Hibernian Order, and that these are the most brutal type of warder. …

Moss looks very ill, but his spirit is indomitable, and his friends will have the utmost difficulty in inducing him to take any rest. Another sentence of two months hard labour from which he has appealed is still hanging over him. Will the government have the brutality to execute it?”[37]

Three days of Moss’ sentence was commuted and he was released 25th February 1914. Anindication of the toll this hunger strike took can be seen in the fact that, on imprisonment, Moss weighed 141lbs (64kg), and on release he weighed 109lbs (49kg), a loss of 32lbs (15kg) in 11 days.

The long adjourned appeal against Moss’ first two convictions for intimidation took place shortly after his release from his second term in Mountjoy. But, due to an administrative error, the appeal was adjournedagain until June, 1914 when the charges were finally dismissed.[38]

The Irish Citizen Army

In addition to Moss’ role as a union organiser he was involved in the formation of and recruiting for, the Irish Citizen Army(ICA). The ICA was formed on19th November, 1913 as a response to the perceived partisan brutality of the Dublin Metropolitan Police against strikers and picket lines.

At the time of the formation of the ICA Frank Moss was serving his first term of imprisonment in Mountjoy. However, he was present at the event which prompted the reorganisation of the ICA. On 13th March, 1914 a labour demonstration was held at Beresford Place where:

“…addresses were delivered by Messrs J. Connolly, P.T. Daly, W.P. Partridge, T.C., Captain White and Countess Markievicz….Messrs Daly and Partridge, on concluding their speeches left the meeting. Countess Markievicz…remained with the crowd as also did Walter Carpenter and Mr Frank Moss (Transport Union Organiser)”[39]

At the end of the meeting Captain White, the officer in charge of the ICA, led a march upon the Mansion House. Along the way, a scuffle with the police developed into a melee in which Captain White was injured and arrested, despite the efforts of the ICA. Following Captain White’s arrest, Countess Markievicz, Walter Carpenter and quite possibly Frank Moss visited the police station in which he was being held.As a result of this defeat at the hands of the police it was decided the ICA would be reorganised upon more formal lines.[40]

On 22ndMarch, 1914, the army council of the ICA was formed and Frank Moss was elected to the committee.[41] Moss used his popularity and influence with the farm labourers torecruit for the ICA throughout North County Dublin:

“On Friday, April the 24th, an enthusiastic meeting was held in Finglas, over which Frank Moss presided, and the speakers were, M. 0’Maolain, J. Magowan and S. O’Cathasaigh. So in spite of many difficulties the Irish Citizen Army was making steady progress, and companies now had been formed and were actively drilling in Clondalkin, Lucan, Swords, Finglas, Coolock, Kinsealy and Baldoyle.”[42]

A large meeting was held in Swords on 15th March, 1914, attended by over 500 people. A body of the ICA marched from Dublin and the meeting was addressed by James Connolly, Countess Markievicz, P.T. Daly and W.P. Partridge. It would be unlikely that such significant a gathering in Swords would not also have been addressed by Frank Moss.

The Rest of Moss’ Story

One of the last mentions of Frank Moss in the press finds him still in Swords. During the June 1914 election campaigning for the County Council and Rural District Council,James Larkin addressed a gathering in Swords. His speech attacked Mr John Patrick Cuffe, JP DC, the opposing local candidate, who was present.When Cuffe took the platform he mounted such a solid defence that he won the support of the crowd. Following his speech, Cuffe was heckled by Frank Moss, but in the end, with little support in the crowd, Jim Larkin and his speakers left Swords[43]. Moss would have had good reason to hold a grudge against Cuffe as he was a local land owner and farmer who had served on several magistrates’ hearings to dispossess striking farm labourers of their homes.

From mid-1914 onwards there is no significant mention of Frank Moss in the newspapers or official records. He died of TB in 1925.

From mid-1914 onwards there is no significant mention of Frank Moss in the newspapers or official records. He is not listed among those ICA members who took part in the 1916 Easter Uprising, and he was not among those arrested or interned in connection with it.His name does not appear in any records in connection with either the War of Independence or Civil war.[44]

It is possible Moss remained in Swords after the end of the strike working for the ITGWU and ICA. Or perhaps after the defeat of the farm labourers strike and lockout, Moss, by now a high profile figure, was blackballed and prevented working in Swords and the surrounding districts. If that were the case he would likely have sought work in Dublin, probably living in the overcrowded tenements.

The only record I can locate after 1914 regarding Moss is his final record, his death certificate, which presents us with one final mystery. Frank Moss died 9th April, 1925, 55 years of age. The cause of death was tuberculosis, duration six months, at the Alan Ryan Hospital, Pigeon House Road, Ringsend, his profession given as labourer. However, one intriguing question is presented by his last known address – 31 Marlborough Street, Dublin.

In June 1924, ten months before Moss’ death, 31 Marlborough Street was purchased as the new premises of James Larkin’s Worker’s Union of Ireland, the address to be known as ‘Unity Hall’. James Larkin had his offices at ‘Unity Hall’, and, it appears, Frank Moss was living there. It is unknown if Moss was actually working for Larkin’s new union, or if Larkin was letting an old comrade and union foot soldier stay there because he was perhaps too ill to work and had nowhere else to go.

Why remember Moss?

So, in the end, why is Frank Moss’ story worth telling? He was, first and foremost, a man drawn from the ranks of those he represented, a poor man and a manual labourer.He was also a leader and a motivator, someone who made the farm labourers of the Swords district the most unionised and militant in County Dublin.

While Moss certainly was not a ‘great’ man like Larkin or Connolly, he experienced the farm labourers’ strike and Dublin Lockout in a way that many of the other senior union officials did not.

Perhaps a testament to Moss’ effectiveness as a union organiser can be seen in the orchestrated campaign on the part of the authorities to ensure his removal from the Swords district. He was subjected to violence, travesties of justice, repeated imprisonment and forced feeding. He clearly had a fierce belief in his convictions and the strength to endure two terms in prison and two hunger strikes, the last almost breaking his health, without backing down.

Ultimately though, he endured the same fate as the men he led out on strike in 1913, to be unemployed, hounded by the authorities, dispossessed and, for all his efforts, to be forgotten by later generations.

Moss experienced the farm labourers strike and Dublin Lockout in a way that Connolly, Larkin and many of the other senior union officials did not, at the front lines, in the riots, confronting ‘scabs’ in the pubs and police in the streets, watching his men struggling to feed families under a roof they did not own.

While Moss certainly was not a ‘great’ man like Larkin or Connolly, they would not have been able to achieve anything if it were not for the Frank Moss’s and others like him, the tireless foot soldiers of the union movement, the motivators and organisers, the hard men andstreet fighters, and, on occasion, the martyrs and men who gave up their liberty and became symbols of a struggle. Frank Moss was all of those things.

As such, just as he once stood beside them in life, Frank Moss deserves to have his name written on the same page of history as that of Larkin, Connolly, Markievicz, Daly, Partridge and Carpenter, as a simple man who fought on the side of labour in 1913.

Post Script

There are many questions left unanswered in the story of Frank Moss, but perhaps this article will prompt others to search for the remaining answers. As yet I have been unable to locate a photograph of Moss; perhaps one will yet turn up. What became of his wife? His death certificate lists him as a widower but I have been unable to locate a record of when she died. On his 1913 prison records it lists his next of kin as his son, William Moss, Westmeath. It would be wonderful if this article were to generate enough interest to locate a descendant of Frank Moss.

Finally, and most importantly, I have been unable to find the location of Frank Moss’ burial. I hope that his grave is marked, but if not, perhaps this incomplete telling of his story can serve as his epitaph.

References

[1] Place of birth is also give as Garristown, a nearby larger village.

[2] Mary Ellen Gleeson lived at 14 Prebend Street and Moss lived at 24 Constitution Hill.

[3] Irish Independent, 18 September, 1913, Page: 5

[4] Irish Times, 1 November, 1913, Page: 4

[5] Irish Times, 25 October, 1913, Page: 9

[6]Irish Times, 7 October, 1913, Page: 6

[7] Daily Herald, 27 January, 1914

[8] Irish Independent, 29 September, 1913, Page: 7

[9] Irish Independent, 18 September, 1913, Page: 7

[10] Irish Independent, 22 September 1913, Page: 5

[11] Irish Times, 27 September, 1913, Page: 3

[12] Irish Times, 2 October, 1913, Page: 5

[13] Irish Independent, 10 October, 1913, Page: 8

[14]Irish Independent, 10 October, 1913, Page: 5

[15] Irish Independent, 17 October, 1913, Page: 9

[16]Irish Independent, 10 October, 1913, Page: 8

[17] Irish Times, 16 February 1914, Page: 6

[18] Freeman’s Journal, 13 October, 1913, Page: 5

[19]Freeman’s Journal, 13 October, 1913, Page: 5

[20]Freeman’s Journal, 13 October, 1913, Page: 5

[21]Freeman’s Journal, 13 October, 1913, Page: 5

[22]Freeman’s Journal, 13 October, 1913, Page: 5

[23] Freeman’s Journal, 25 October, 1913, Page: 8

[24] Freeman’s Journal, 25 October, 1913, Page: 8

[25]Irish Times, 7 October, 1913, Page: 6

[26]An article from the Irish Times, 1st December 1913, refers to the “…forcible feeding of prisoners in Mountjoy” suggesting more than one prisoner was being forcibly fed during the period of the lockout. While researching Frank Moss’ hunger strike I located a reference to another prisoner, Arthur Fagan, forcibly fed in Mountjoy during the same period. Fagan, of 16 McGuiness Buildings, Church Street, was a labourer imprisoned on a charge of loitering with intent to commit a felony. He commenced a hunger strike 30th September 1913 and was admitted to the prison hospital where force feeding commenced on 6th October. While I have no direct evidence, it is quite possible Fagan was a striking worker arrested and imprisoned during the lockout.

[27] GPB/SFRG/1/24 “General Prisons Board file on Frank Moss [of the Irish Transport Union] during his period in custody, October 1913-February 1914”

[28] Freeman’s Journal, 15 November, 1913, Page: 9

[29] Irish Times, 17 November, 1913, Page: 3

[30] Irish Times, 1 December, 1913, Page: 5

[31] GPB/SFRG/1/24 “General Prisons Board file on Frank Moss [of the Irish Transport Union] during his period in custody, October 1913-February 1914”

[32] Daily Herald, 27 January, 1914

[33] GPB/SFRG/1/24 “General Prisons Board file on Frank Moss [of the Irish Transport Union] during his period in custody, October 1913-February 1914”

[34] GPB/SFRG/1/24 “General Prisons Board file on Frank Moss [of the Irish Transport Union] during his period in custody, October 1913-February 1914”

[35] Irish Times, 16 February 1914, Page: 6

[36] Daily Herald, 26 February 1914

[37] Daily Herald, 26 February 1914

[38] Irish Independent, 22 June, 1914, Page: 6

[39] Irish Independent, 14 March, 1914, Page: 5

[40] “The Irish Citizen Army, 1913-16: White, Larkin and Connolly”, D. R. O’Connor Lysaght, History Ireland, Vol. 14, No. 2, (Mar. – Apr., 2006), pp.16-21

[41] The Story of the Irish Citizen Army, Sean O’Casey, 1919

[42] The Story of the Irish Citizen Army, Sean O’Casey, 1919

[43] Irish Times, 8 June, 1914, Page: 9

[44] WS Ref #: 1766 ,William O’Brien