Book Review: Buck Whaley: Ireland’s Greatest Adventurer

Buck Whaley: Ireland’s Greatest Adventurer by David Ryan

Buck Whaley: Ireland’s Greatest Adventurer by David Ryan

Published by Merrion Press, Newbridge, 2019

ISBN: 9781785372292

Reviewer: Gordon O’Sullivan

“Buck Whaley lacking much in cash

And being used to cut a dash

He wagered full ten thousand pound

He’d visit soon the Holy Ground”

Can you admire an 18th century serial spendthrift who managed to burn his way through the modern equivalent of €100 million? David Ryan in his assured new biography, Buck Whaley: Ireland’s Greatest Adventurer, certainly makes a compelling case for Whaley being one of the great characters of a character-packed era.

Drawing on some unpublished and hitherto unused sources as well as Whaley’s celebrated memoirs, Ryan plots the crazy-paving course of a life full of incident and adventure. A life of incredible profligacy, reckless bravery and daring foreign travel in an age where travelling abroad was neither simple nor safe.

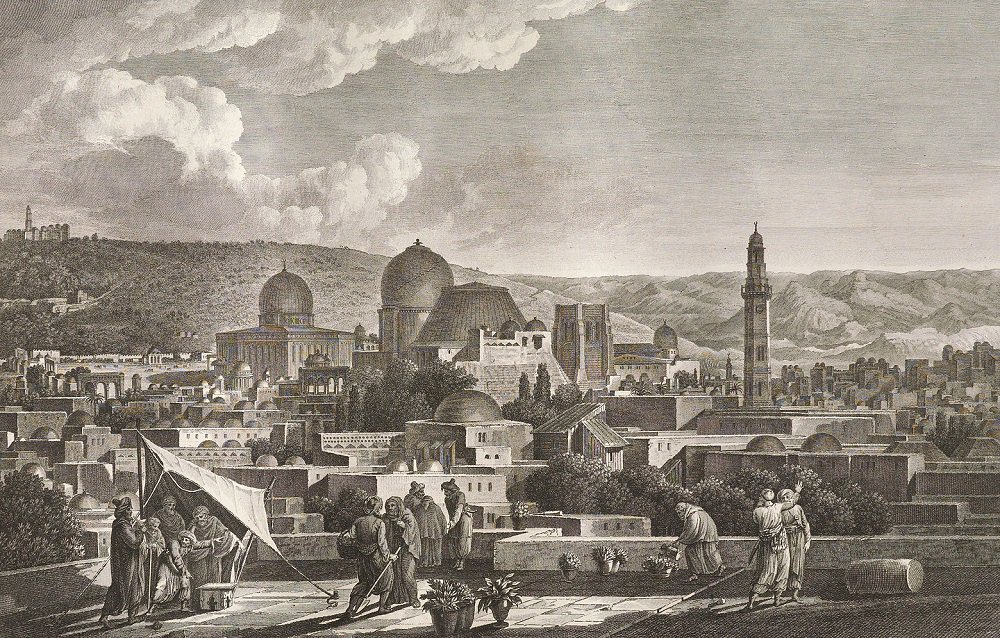

Buck Whaley enjoyed fame in his own time due to an astonishing bet made in 1788 with the Duke of Leinster and his cronies to travel to Jerusalem and back to Dublin within two years.

Buck Whaley enjoyed fame in his own time due to an astonishing bet made in 1788 with the Duke of Leinster and his cronies. As Ryan underlines, gambling was “one of the great obsessions of the eighteenth century” and Whaley was even more addicted than most of his class. Whaley wagered that he could travel to Jerusalem, secure proof of his stay and return to Dublin, all within two years.

The potential winnings were incredible – £15,000, about €5 million in today’s money. To the modern ear, that sounds like a straightforward exercise but for most Europeans in that time, the journey was fraught with dangers and no-one believed Whaley could achieve his goal. In typically flamboyant style, Whaley sailed away on a yacht, serenaded by singers and accompanied both by servants and barrels of Madeira wine.

Whaley started his life in a much more sedate fashion however. A Dubliner born into the wealthiest surroundings imaginable. He would inherit large estates, fine houses and an annual income of £7,000 from his infamously anti-Catholic father, Richard Chapell Whaley.

‘Ill-considered escapades’

Unfortunately for Whaley, but not for his biographer, his father died when he was but two years old. The absence of the father and the doting, forgiving nature of his mother would prove to be a ruinous combination when the sixteen-year-old Whaley went on his first wild adventure, the Grand Tour requisite for 18th century gentlemen.

In this engaging, pacy and persuasive biography Ryan has used many archival sources to keep up with Whaley’s “tendency to set off on ill-considered escapades”, his “obsession with achieving what few or none had accomplished before”, and his “cavalier attitude towards danger.”

As a young gentleman in 1780s Paris, Buck lost £14,000 in one night at cards, fathered an illegitimate child, contracted venereal disease and attempted to abduct an heiress.

Those characteristics make him a fascinating subject for a biographer but made Whaley an inveterate gambler in every element of his life from the gaming tables to the bedroom, “In an age notorious for its gamblers, he was one of the worst”. Living in Paris with a completely outmatched chaperone, Whaley quickly settled into the picaresque pattern that dominated his life and lifestyle.

He would gamble outrageously; he would be taken advantage of by card sharpers and cheats; he would finally be bailed out by his family or friends. His Parisian adventures soon encompassed losing £14,000 in one night, fathering an illegitimate child, contracting venereal disease from repeated visits to a courtesan and ending up mixed up in a lunatic scheme to abduct an heiress. Whaley was finally forced to leave Paris when his bankers refused to honour his colossal debts.

Rescued by his stepfather and returned to Dublin “distressed and disarrayed”, Whaley was “’treated like the prodigal son” and seemed to be “transforming into a responsible and charitable member of society”. For an all too brief moment, it appeared that the now eighteen-year-old Whaley was maturing. He was elected to the Irish House of Commons and lived quietly in rural Ireland. It was, however, a short interlude before he made his famous bet and set out on his Jerusalem adventure.

Voyage to Jerusalem

In one of many rash relationship decisions, Whaley elected to voyage with Captain James Wilson, an undependable and corrupt former Marine.

Wilson was eventually left behind and replaced with a much more “committed member of the expedition” in fellow Irishman Captain Hugh Moore whose unpublished journal on the Jerusalem expedition is used judiciously by the author.

Despite nearly killing himself in St. Michael’s Cave in Gibraltar due to his determination to descend “at least, as far as any other person had ever been”, Whaley and Moore made their way to Smyrna, escaping pirates along the way, and from there journeyed overland to Constantinople.

There Whaley became gravely ill and for a while it “seemed that he and his great adventure would expire on a sickbed in Constantinople”, disease being the one thing that seemed to genuinely scare him. When he recovered though he put his formidable charm to work. His personal charisma must have been extraordinary as he managed to charm men and women of all nations and all religions.

Ahmed al-Jazzar, ‘The Butcher’, facilitated his onward journey from Acre to the prized destination, Jerusalem

His relationship with the British Consul “allowed the Irishmen to mingle freely” among “Constantinople’s European elite” while the Ottoman Vizier Hasan Pasha provided Whaley with the required permits to visit Jerusalem. Even the infamous Ahmed al-Jazzar, ‘The Butcher’, facilitated his onward journey from Acre to the prized destination, Jerusalem. Even on the last leg of his long trip, Whaley was able to negotiate his way through hostile desert before finally arriving in the Holy City.

His charm had, of course, already prepared the way with a letter from the Spanish ambassador in Constantinople providing safe and sanitary accommodation in the Convent of the Terra Sancta. Jerusalem did seem to work its magic on Buck, he was charmed and inspired by the city, visiting all the pilgrimage sites and remaining respectful of the pilgrims. Staying for a month he got the proof he needed to win the bet before his relatively uneventful return journey to Dublin.

Ten months after his bet, Whaley, soon to be known as Jerusalem Whaley or Buck, arrived back in Dublin triumphant. As Ryan underlines, “magazines and newspapers in Britain and Ireland had maintained a keen interest in his affairs” while he was away, and bonfires were lit as he sailed into Dublin. When he had calculated his profits from his Jerusalem adventure, he had £7000 in his pocket, “the only instance in all my life before, in which any of my projects turned out to my advantage”.

Second Act

Only 23 years of age, Whaley now set out to enjoy the benefits of fame and “any sense of piety or perspective he had acquired on his travels was soon discarded” as he “embraced a life of expense and excess.”

The second half of Whaley’s life takes up far less space in Buck Whaley: Ireland’s Greatest Adventurer yet, is, in itself, the stuff of novels. His gambling problems worsened and his debts piled up, reinforcing a natural restlessness eventually leading him back to Paris in the midst of the French Revolution. In typically madcap style he “attired himself ‘like a true Sans culotte’” and tried to rescue Louis XVI from execution.

‘Buck’ dissipated an enormous fortune before dying at the age of just 33.

He set up a faro bank in Paris, one of his infrequent financial successes, before fleeing from the revolutionaries to Switzerland and thence to a debtor’s prison in London. Incredibly this was the one and only time he ended up in jail for his jaw-dropping debts. Even then he his release was secured by his brother-in-law. By now Whaley had no more estates to sell to clear debts, he had “dissipated a fortune of near £400,000” without enjoying “one hour’s true happiness”.

Whaley moved to relatively quiet exile in the Isle of Man where “perhaps to his surprise, he had found peace of a kind”. On the foot of some successful gambling, he bought a parliamentary seat in Enniscorthy whereupon he used his position to solicit bribes to support the Act of Union, then to oppose the Act, and finally to support it.

His end, when it came at thirty-three, was surprisingly free of drama, dying in Knutsford in Cheshire from rheumatic fever. Naturally rumours sprang up at once that he had been murdered.

In David Ryan’s Buck Whaley: Ireland’s Greatest Adventurer, Whaley has got the biographer he merits

This quite remarkable character, said to be the inspiration for both the characters of Barry Lyndon and Phileas Fogg has been very well served by his biographer, David Ryan. The author’s fluent writing style render his research skills easily accessible. The pace of this biography is novelistic and almost unrelenting as the reader is continually astonished by the scale of Whaley’s expenditure, the audacity of his personal conduct and the bravura with which he took on the world.

In Ryan’s view, Whaley “transcended the world of rakes, gamblers, and adventurers. His legacy is greater and more significant than that.” But is it?

Ryan is least convincing on the lasting significance of Buck Whaley. The reader hears Whaley’s own words but remains curiously unsympathetic to someone who had so much and spent even more.

Whaley was admirably brave but had a psychological need to push physical boundaries, compulsively reckless with his own money and with others’, self-destructive but also capable of wreaking pain, debt and in one case, death on those closest to him. A litany of sins offset Ryan argues by his realisation that “his lavish life of privilege was a mere accident of birth” and travelling “did bring him closer to his essential humanity”.

The author is more convincing when he states that despite struggling with his “deep human frailties”, he “hurled himself into one of the greatest adventures of the age”. And it is as one of the great adventurers of his age and a gambler emblematic of the great passion and vice of the 18th century that Whaley deserves to be remembered. In David Ryan’s Buck Whaley: Ireland’s Greatest Adventurer, Whaley has got the biographer he merits.