Book Review: Everyday Violence in the Irish Civil War

By Gemma Clark

By Gemma Clark

Published by Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Reviewer: John Dorney

In this book, the author, Gemma Clark, attempts to quantify and explain ‘everyday violence’ in the Irish Civil War of 1922-1923. By this she means violence primarily against property and sometimes against the persons, of civilians, rather than military clashes between the combatants during the war over the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

This is a subject of much interest, considering that the Civil War, coming at the end of the Irish Revolutionary period of 1916-23, involved fairly small scale military encounters but very widespread destruction of infrastructure and property. The author has also summarised her arguments in a chapter of the recent ‘Atlas of the Irish Revolution’.

Clark argues that the Civil War was ‘the final reckoning of ancient enmities, settling local scores and purging the community of the old enemies, tyrannical landlords, ex-servicemen, southern Unionists and Protestants’

She certainly has a provocative argument. ‘Was the Civil War’ (p.58), she asks, ‘a military and political campaign to destabilise the Free State? Or did the Civil War provide the conditions for the final reckoning of ancient enmities, settling local scores and purging the community of the old enemies, tyrannical landlords, ex-servicemen, southern Unionists and Protestants?’

She reiterates in her conclusion (p.197) that the purpose of anti-Treaty violence was to ‘regulate community relations and purge Munster of unwanted persons’.

In other words, the war between Free State forces and the anti-Treaty IRA was just a cover for a low level campaign to drive out southern Protestants and unionists and other unwanted minorities.

Sources

This book grew out of the author’s PHD, which was a study of three Munster counties, Limerick, Waterford and Tipperary. Specifically it is based on the compensation claims of ‘southern Irish loyalists’ who applied for compensation to the British government for damage or injury inflicted during the Irish revolution, and of compensation appeals to the Irish Free State, for losses incurred by its supporters at the hands of anti-Treaty or Republican forces.

This book is based on study of counties, Limerick, Waterford and Tipperary and of the compensation claims to British and Free State governments, mostly for damage done to property.

Therein lies the first problem. These sources only tell us about the ‘everyday violence’ inflicted on supporters of the British or Free State governments and nothing about that suffered by Republican supporters, either before the Truce of July 1921, or, particularly, those who supported the anti-Treaty side in the Civil War. As a result, this is a very lopsided picture of the violence borne by civilians in the period.

Moreover, those applying for compensation, in order to receive it, had to show that the damage wrought on their property was as a result of their loyalty to either the British or the Free State governments.

The period of the Civil War was a highly anarchic time, in which one state, Britain, departed, with its armed forces and police, and another, the Irish Free State, was born under the most chaotic conditions imaginable. In this vacuum of law and order, thousands of local disputes, mostly agrarian or labour related, as well as settling of scores from the preceding War of Independence, flared.

In the south and west particularly there was an epidemic of land occupations and ‘cattle driving’ and, at the same time, strikes, mostly by agricultural workers and particularly in the south east, often turned to violence.

These sources mean that violence against republicans or their supporters is not discussed.

All of this, in truth, was only very tenuously related to the conflict over Irish independence and yet it was undoubtedly responsible for much of the violence against property in the period.

And yet farmers who had their hay ricks burned or their land occupied by the landless, or their cattle driven off by the small farmers who wanted to work the land, or creamery owners whose property was occupied by striking workers, had to present this as the work of the ‘Irregulars’ or anti-Treaty IRA, if they wanted compensation.

Agrarian, labour and political violence

In some areas of course there was a crossover between disgruntled smallholders or strikers and IRA members, but for the most part these were separate phenomena.

However Clark appears to take at face value the claims in the compensation files that all the violence of 1922-23 that was attributed to anti-Treaty Republicans was in fact carried out by them. This is a very problematic assumption, which colours much of the rest of the book.

Waterford, Tipperary and Limerick saw intensive labour and land conflicts that ran parallel to the political and military conflict over the Treaty.

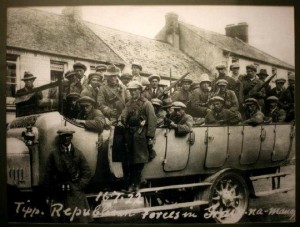

To illustrate this, the counties that Clark chooses, Limerick, Waterford and Tipperary, were in fact the centres of very intense labour struggles. Limerick and Tipperary saw a wave of factory and creamery occupations in early 1922 by workers protesting at wage cuts and lay-offs. The red flag of socialism briefly flew over these ‘Soviets’ before they were eventually seized and handed back to their owners by the Free State’s National Army.

Similarly, rural County Waterford saw what amounted to a general strike by agricultural workers in the summer of 1923 – after, it should be noted, the IRA ceasefire of May 1923. To put the strike down, the Free State declared Waterford a ‘special military area’ and deployed the Special Infantry Corps – a unit raised to put down social disorder, or as Kevin O’Higgins put it, ‘passive irregularism’. As, for instance Gavin Foster has shown, the Special Infantry Corps and a farmers’ strong-arm organisation calling itself the ‘White Guards’ took to burning strikers’ houses as ‘the only way to stop the labour burners’. [1]

Waterford, Tipperary and Limerick saw intensive labour and land conflicts that ran parallel to the political and military conflict over the Treaty.

None of this can be found in Clark’s book. Which is a pity because it leads to confusion on Clark’s own part as she fails to separate violence into categories from which it may be understood – i.e. violence relating directly to the political conflict, local land disputes, agrarian strife and labour conflicts. Nor can any straightforward connection be made between such violence against property and sectarianism.

Clark appears to recognise these arguments at times, writing for instance, that the normally Catholic ‘grazier’ or big cattle farmer was a more common target of land hunger than the stereotypical Protestant landlord: (p.115) ‘it was mostly a campaign for redistribution directed at the grazier and medium sized farmer’.

She writes of the perpetrators of labour related violence (p.93), ‘clearly not all incendiary gangs were the anti-Treaty IRA’ and notes that the IRA, especially in the Truce period before the Civil War, usually condemned violent land agitation and often re-possessed illegally seized land. (p.135)

Despite this, her conclusion is still that violence was used ‘to clear out minorities’ (p.100).

Simply put, the evidence she herself presents does not bear this out. Of the houses and property she found burned in the three counties of her study, only 19% were deemed to be ‘attributable to allegiance the United Kingdom‘.

If much of the low level violence against property in the period was not carried out by the IRA or even by their supporters, and if former unionists (let alone Protestants as whole) were only a minority of victims, does it not disprove the theory that the Civil War was really a concealed ‘ethnic conflict’, under the cover of the war against the Treaty?

Was it not in fact the opposite, that the Civil War, caused by the split in Republican ranks over the Treaty, heralded a period of anarchic violence in the absence of state power, that involved multiple actors – agrarian, labour and others, as well as the Republican guerrillas?

Big House burnings

The burning of the ‘Big Houses’ or mansions of the the Anglo-Irish gentry class, was unquestionably an action carried out by the anti-Treaty IRA during the Civil War.

Clark again attributes this (p.67) to the destruction of ‘strongholds of British agents, that is of loyalists left behind by Britain to sabotage independent Ireland once the war was over’. Again, this is the idea that the Civil War was just a cover for a more fundamental objective.

This brings us to a second and related problem of sourcing. Clark laments (p.159) that there are ‘sparse’ sources available from Republicans dealing with the conduct of the Civil War. In their place she cites several Republican memoirs – some of which, such as Tom Barry’s ‘Guerrilla Days in Ireland’ do not in fact deal with the Civil War period at all.

There is also some very problematic use of fiction, including Colm Toibin and Sebastian Barry’s novels (written since the 1990s) as a source to illustrate IRA thinking.

However, in reality there is no paucity of primary sources from within the anti-Treaty IRA. The Twomey Papers, which are to be found in the archives of University College Dublin, contain all the IRA Chief of Staff correspondence of the Civil War period, including communication with every regional Brigade, IRA Intelligence files and more. In these can be found often painstakingly detailed reports of actions at the most local level conducted by the anti-Treaty guerrillas.

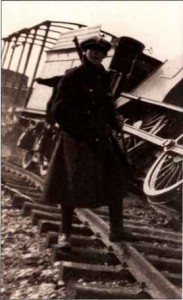

These include most categories of ‘everyday violence’ carried out by the anti-Treatyites, including house burning, road and rail destruction, fines imposed on civilians and seizure of property, as well as the more dramatic ambushes and assaults on Free State positions.

They were simply not consulted for this study. As a result, Clark’s insights into anti-Treaty IRA motivations are, at best, limited.

Nevertheless, Clark’s argument about the Big House campaign is not entirely incorrect. The IRA and in particular, its Chief of Staff, Liam Lynch did see ‘Big House unionists’ as ‘imperialists’ and he sometimes also referred to former unionists in general as ‘the enemy civilian garrison’.[2] Lynch assumed that the owners of Big Houses were automatic supporters of the Free State and what he considered the betrayal of the Irish Republic that the Treaty represented.

However the burning campaign against the Big Houses, as Lynch’s General Orders make clear, was a product of the Civil War, not a part of some grand design to purge Irish society of unwanted elements.

There was one spate of burning in the late summer of 1922, when anti-Treaty forces abandoned their fixed positions and were ordered by Lynch to burn military and police barracks and any other building – including workhouses and country mansions – that could be used as garrisons for Free State forces.

There may have been some symbolic effect attached to this as Clarke suggests, but it was mainly a military decision of a guerrilla army based on denying garrisons to their enemy.

However, those represent a minority of Civil War house burnings. Almost all the Big House burnings occurred after December 1922, when in reprisal for the Free State execution of four senior Republicans in Mountjoy Prison, Lynch issued a general order to all units that ‘all Free State supporters are traitors and deserve the latter’s stark fate, therefore their houses must be destroyed at once.’[3].

On 26 January 1923, the anti-Treaty IRA Adjutant General Con Moloney, issued the following order:

- Houses of members of ‘Free State Senate’ in attached list marked A and B will be destroyed.

- From the above date if any of our Prisoners of War are executed by the enemy one of the Senators in the attached list … will be shot in reprisal.[4]

Many members of the Senate were of the old gentry class. Some others who were targeted were simply presumed to be ‘Imperialists’ because of their background. There was certainly an element of social and sectarian prejudice at work in targeting what the Adjutant General of the IRA described as ‘imperialists and freemasons’[5].

But to ascribe a simple sectarian motive to the house burning campaign is to radically over simplify.

First of all, the house burning campaign was intended not as a campaign of ethnic cleansing but as a reprisal to deter executions (in which it failed). Nor were all of those identified as ‘Imperialists’ Protestants.

Take the case of Senator Bryan Mahon, whose house at Ballymore Eustace was destroyed by the IRA in February 1923. Mahon was identified by the IRA as an ‘imperialist and freemason’. He had been commander of British forces in Ireland from 1916-18 and had commanded the 10th Irish Division at Gallipoli before that. But he was in fact a Catholic, born in Galway.

Secondly, ‘small houses’ were targeted as often as big ones, notably that of TD Sean McGarry, whose seven year old son Emmet died in the blaze, and of government ministers WT Cosgrave and Kevin O’Higgins. And these burnings of ‘Free Stater politicians’ homes were often much more violent than those of the Big Houses. O’Higgins father was shot and killed when his house was burned, as was Cosgrave’s uncle in a raid on his business.

The evidence suggests that those carrying out the Big House burnings were not motivated by hatred or personal animosity for the most part, but rather felt they were simply carrying out orders, however distasteful.

IRA men in Kildare, for instance, charged with setting alight Palmerstown House told Lord and Lady Mayo they were going to burn the house in reprisal for the executions of their men that day at the Curragh but intended them no harm.

‘Are you going to shoot me?’ Lord Mayo asked. “No, my lord: we are not going to shoot you, but we have our orders to burn the building.” “It is only right to say”, Lord Mayo recalled, “that the raiders were excessively polite”. [6]

In Louth, the IRA burned six ‘Big Houses’ in retaliation for six executions at Dundalk in early 1923. One victim of the arsonists, John Russell who was a county sherrif, asked the burners if he was targeted because he was a Protestant. They replied that they ‘cared nothing for religion’ and the burning was in retaliation for the executions and because he was a ‘government official and sympathiser’.

In March 1923 the IRA in Louth burned Knock Abbey, the stately home of William O’Reilly, a Catholic. It was rumoured locally that they had been ordered to burn a Catholic owned home in response to allegation of sectarianism.[7]

In short the house burning campaign was an effort at reprisal at Free State supporters, real and perceived, not a campaign of ethnic cleansing.

And if the anti-Treaty IRA was bent, as its primary aim, on eliminating Protestants in general and the landed upper class in particular, from southern Irish society, it seems odd that so many of the members of this class were involved at senior levels in the Republican movement, including anti-Treaty, post 1922, Republican, movement.

Erskine Childers (executed by the Free State in November 1922) was one. His fellow member of the Treaty negotiating team, Robert Barton was also of this class. Famous republican propagandist and activist Constance Markievicz (nee Gore Booth) the scion of the aristocratic Gore Booth family from Lisadell House, was too. So was David Robinson (Childers’ cousin), who commanded anti-Treaty guerrillas in Kerry until his arrest, and so was Charlotte Despard (the sister of Sir John French the Commander in Chief of the British Army in 1914 and last Lord Lieutenant of Ireland), who organised the Republican prisoners’ benefit campaign.

All of which is not to suggest that there was no sectarianism or class prejudice in anti-Treaty Republican ranks; there was. Nor is it to suggest that the campaign against the Big Houses in particular was not in part motivated by prejudice.

But it is to suggest that sectarianism in no way comprised the main thrust of the Republican political or military efforts either in the independence struggle or in the subsequent Civil War and that even in the campaign against the Big Houses, reprisal, not ‘purging’ was the goal.

Violence against people

Of course, the most significant violence in the Irish Civil War, or in any conflict, was violence against people.

Here, Clark’s book is informed by the work of Stathis Kalyvas, whose ‘The Logic of Violence in Civil War’, based on a study of the Greek Civil War of the 1940s, argues that civil wars degenerate into local feuds, that essentially become cyclical and divorced from politics or ideology.

Clark, correctly, in my view, disagrees with this thesis in respect of the Irish Civil War, writing, (p.179) ‘The IRA did not use the breakdown of law and order caused by the Civil War to perpetrate unfettered violence on civil society’ and (p.186) ‘there is little evidence that serious violence against and between civilians or friends and neighbours became commonplace’.

Summing up, she writes:

(P.194) ‘The anti-Treaty IRA in Munster certainly waged a costly war and succeeded for a time in undermining the authority of the new government. The insurgents did not, by contrast, regularly use lethal force against persons to control or coerce the population’.

Clark appear to make a contradictory argument, that serious violence against civilians was not common but that the Civil War was really an attempt to drive out ‘the local enemy’ or Protestants and unionists.

However, perhaps hemmed in by her original thesis of the Civil War as an ethnic or sectarian conflict, she also writes (p.186) that the IRA wanted ‘to drive from Ireland the local enemy (Protestants, landlords, graziers and Fee Staters)’.

But surely both things cannot be true. If the IRA did not commit widespread lethal violence on civilians but rather focussed most of its attacks, shootings and bombings on the Free State’s National Army (who lost about 900 killed and thousands more injured in the war), then surely that, the military campaign against the pro-Treaty government, was the main focus of the Civil War? Violence against civilians was a by-product, not a driving force of events.

There are a number of other issues I wish the book had explored further. The first is that in the Civil War there was far less targeting of civilians by all sides than in the preceding War of Independence (1919-21). In the war against the British, the pre-split IRA systematically shot informers and alleged informers: around 200 being killed, mostly in the first six months of 1921.

It was here that in some areas, most notably Cork, the thesis of sectarianism has some weight. Protestants were overrepresented in the IRA’s killings of informers in Cork in 1921, according to Thomas Earls Fitzgerald’s figures, which state that eight out of ten informers shot by Tom Barry’s Third Cork Brigade in January and February 1921 alone were Protestants – well out of line with their share of the population (about 16 per cent) in West Cork.[8]. Whether this was due to their activities as informers or whether the IRA wrongly suspected them based on their religion remains a topic for debate.

The salient factor about the Civil War however, was that the anti-Treaty IRA shot very few civilians of any religion as informers: around 6 in County Cork for example compared to about 70 before the Truce.

In fact there were general orders from Liam Lynch, issued in September 1922 that civilians could only be shot if IRA GHQ gave explicit permission and that would only be given if their actions had resulted in the death of a Republican Volunteer.[9] In this respect Lynch was much more discriminate than his predecessor as IRA Chief of Staff, Richard Mulcahy had been.

These orders were eventually rescinded after the Free State began executing prisoners. But such killings of informers never came remotely close to the level of executions of informers in the ‘Tan War’. The Tipperary units, whose IRA commander Dan Breen was exceptionally ruthless, in this regard, killed five civilians as spies in the Civil War compared to 16 such killings there before the Truce.[10]

Similarly while British forces before the Truce of July 11 1921 systematically destroyed property in reprisals for IRA attacks and frequently killed civilians too, there was no such policy by Free State forces in the war of 1922-23.

Which is not say that Free State forces were innocent of any wrongdoing. In Tipperary, one of the counties chosen for study here, by my count the National Army killed seven civilians and nine anti-Treaty prisoners as well as executing four judicially. In counties like Dublin and Kerry their record was considerably worse. But as the focus here is on Republican violence only, state violence is not discussed in ‘Everyday Violence in the Irish Civil War’.

The Phoney war

And a third distinction that I felt should have been made was singling out of the period between the Dail’s ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in January 1922 and the start of the Civil War on June 28 1922. In this six month period, British forces departed but squabbling Irish forces only partially took their place as upholders of law and order.

This was the time when violence in newly created Northern Ireland was at its height, where Catholic civilians were being killed and expelled in relatively large numbers and when, south of the new border, some voices blamed southern Protestants for the ‘pogrom’ on Northern Catholics.

For instance, notices threatening ‘For every Catholic murdered in Belfast two Orangemen will be killed in Monaghan’ were posted in Clones.[11] Brian Hanley has shown that in one locality in Tipperary at least, it was pro-Treaty IRA Volunteers who were guilty of harassment and intimidation of Protestant farmers in this period.[12]

It was during this ‘phoney war’ while pro and anti-Treaty factions shaped up to each other and violence raged in the North, that most of those instances of serious violence against southern Protestants that Clark catalogues, such as the gruesome gang rape of Harriet Biggs near Nenagh in June 1922 by anti-Treaty IRA members, took place. (Incidentally, one of the perpetrators of this crime, Michael Hogan, was later killed himself during the Civil War, abducted and killed by Free State forces in Dublin in March 1923).

It was the six months before the Civil War, not the war itself, that sectarianism in the south of Ireland was at its height.

The infamous shooting dead of thirteen Protestant in West Cork in April 1922 also took place in this time frame of heightened sectarianism, indiscipline among all the armed forces on the ground and a power vacuum.

It was also this period that saw most of the attacks on former RIC policemen, which Clark also sees as an attempt to drive out the reminders of British rule. Though as John Regan noted in his review of ‘Everyday Violence’ it would be more correct to say that killing of ex RIC men in early 1922 was motivated more by revenge for actions they had committed during the War of Independence than as part of some wider plan to purge Irish society of unwanted elements.[13]

The point is though, that these type of attacks were in fact much more common before the Civil War than during hostilities themselves and were often condemned, however ineffectually, by both sides of the Treaty divide. A fact which does nothing to excuse the perpetrators but does rather complicate the argument that they were the main focus of, let alone the reason for, the Civil War.

Conclusion

Clark suggests that the violence catalogued in the compensation files, taken together with the decline in the southern Irish Protestant population after 1922, shows that victimising the minority was ‘unavoidably’ part of the Irish Civil War. She compares this at one point with the mass expulsion of Palestinians from what became Israel in the Arab-Israeli war of 1948.

Though sectarianism was present in various ways among Irish Republicans in the 1920s, it was by no means their central organising principle.

I would argue that this argument is profoundly mistaken and misleading. Though sectarianism was present in various ways among Irish Republicans in the 1920s, it was by no means their central organising principle. In fact they repudiated it publicly and regularly.

During the Civil War itself of 1922-23, civilians were targeted much less frequently by both sides than in the preceding War of Independence and the large majority of deaths in the war over the Treaty were combatants.

The main goal of the anti-Treaty IRA campaign was indeed to bring down the Free State government and the Treaty and not to purge Irish society of unwanted elements. Nor was there a concerted campaign by them to kill or expel southern Protestants.

The ‘everyday violence’ of the Civil War came from numerous sources – including State forces, the land hungry and labour militants as well as anti-Treaty guerrillas.

Clark’s book is important and challenging if, in the opinion of this reviewer, ultimately problematic.

References

[1] Gavin Foster, The Irish Civil War and Society, (Palgrave. 2015) p.140-141. For the ‘White Guard phenomenon, see Conor Kostick, Revolution in Ireland (Cork University Press, 2009), p. 206-207.

[2] De Valera-Lynch Correspondence 15–16 January 1923 in De Valera Papers , UCD P150/1749

[3] Liam Lynch IRA General Orders 9/12/22 in Twomey Papers, UCD P67/2.

[4] O’Malley and Dolan, No Surrender Here!, p. 533.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Dooley, Terence, The Decline of the Big House in Ireland p 174, Leinster Leader, February 3, 1923 and 12 December 1925

[7] Jean Young The Big House in County Louth, 1912-1923, in County Louth and the Irish Revolution, edited by Donal Hall and Martin McGuire. P.158-163

[8] Fitzgerald, Thomas Earls, ‘The Execution of Spies and Informers’, in Fitzpatrick (ed), Terror in Ireland, pp.184-185

[9] IRA General Order No 6, issued 4 September 1922, in No Surrender Here the Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley, Edited by Anne Dolan and Cormac O’Malley, (Lilliput 2007) p.505

[10] See Casualties of the Civil War in Tipperary: https://www.theirishstory.com/2017/04/28/civil-war-casualties-in-county-tipperary/#.W5RJ9PknbIU

[11] Anglo Celt, 6 May 1922.

[12] One of the victims, Richard Pennefather, was a substantial farmer who had ‘got a lot of trouble in the years 1922 and 1923’ when a number of Pro-Treaty IRA men from nearby Turraheen had fired shots into his home, broken his windows and commandeered his car on several occasions, apparently trying to make him abandon and then seize his farm. Brian Hanley, ‘July 1935: Remember Belfast – Boycott the Orangemen!’, The Irish Story, 2013. https://www.theirishstory.com/2013/01/07/july-1935-remember-belfast-boycott-the-orangemen/#.V5TlrqLwruZ. Accessed 31/03/17.

[13] Regan’s review in Irish Historical Studies is available here. https://www.academia.edu/26751115/John_M._Regans_review_of_Gemma_Clarks_Everyday_Violence_in_the_Irish_Civil_War_Cambridge_2015_in_Irish_Historical_Studies

See also Gavin Foster’s review in Dublin Review of Books, http://www.drb.ie/essays/ordinary-brutalities