Dreaming of an “Irish Tet Offensive”: Irish Republican prisoners and the origins of the Peace Process

By Dieter Reinisch

January 30 2018 marked the 50th anniversary of the launch of the “Tet offensive” in 1968 by North Vietnam forces and the National Liberation Front against the South Vietnam Army and the US military presence.

The offensive not only facilitated the changing public opinion in the USA on the Vietnam War and heralded revolutionary unrest throughout the world in 1968, twenty years later, the idea of a Tet-like offensive resurfaced in Ireland.

This piece will argue, however, that rather than a credible scenario, it was a wide-spread myth among the Irish Republican prisoners’ population that facilitated the departure of the IRA from Armalite to the ballot box.

In the 1980s, the Provisional IRA planned for a ‘Tet offensive’ that would radically escalate the conflict in Northern Ireland to force a British withdrawal.

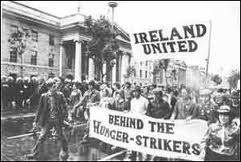

In the 1980s, the Northern Irish conflict was in full swing. The high hopes of experiencing a “year of victory” in the early 1970s had disappeared among Irish Republicans as the conflict turned into what became known as the “Long War.” The hunger strikes in 1981 brought previously unknown public support for Provisional Republicans, one of the two Republican factions that originated from the split of the IRA and Sinn Féin in 1969/70.

By then, the Provisionals were the main Republican faction and had been boosted by electoral victories. Among those was the election of Bobby Sands as MP in the Fermanagh/South Tyrone by-elections while lying on his deathbed in the H-Blocks. Shortly after his election, Sands had died on hunger strike for political status. Tens of thousands packed the streets of Belfast on the day of his funeral.

The Armalite and the Ballot Box

These electoral victories were used to push for a new strategy that Belfast Republican Danny Morrison called “the Armalite and the Ballot box” at the Sinn Féin Ard-Fheis (AGM) in 1981.

In a historic speech, he said: “Who here really believes that we can win the war through the ballot box? But will anyone here object if, with a ballot paper in this hand, and an Armalite in this hand, we take power in Ireland?” These few words were to become the summary of the political program of the Republican movement.

One of the obstacles on the way to parliamentarism was abstentionism. This was a long-standing Irish Republican strategy. It meant that since Republicans did not recognize the parliaments in Dublin, Belfast, or London as legitimate representations of the will of the Irish people, their candidates, even if elected, would abstain from taking their seats in these assemblies. While the strategy worked well in earlier decades of the 20th century, by the 1980s a new generation of Republicans, mainly from the Belfast area, saw it as an obstacle to electoral breakthrough.

“Will anyone here object if, with a ballot paper in this hand, and an Armalite in this hand, we take power in Ireland?” Danny Morrison.

The debate on abstentionism dominated Sinn Féin until the split of the party in 1986. At the 1986 Ard-Fheis, a majority of delegates voted to drop abstentionism to the Dublin parliament. As a result, a much smaller faction, led by former Sinn Féin President Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, walked out and regrouped under the name “Republican Sinn Féin.”

In early 1986, the Provisionals were at a crossroads. The Northern organization, led by a faction of Belfast Republicans, among them Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams, Danny Morrison and others including Martin McGuinness of Derry, were pressing for abandoning abstentionism. This group won the above mentioned factional struggle within the movement later that year – in part because they received the support of the Republican prisoners throughout these years.

Prisoners

Among the IRA prisoners, there were reservations over parliamentary politics. Three factions arose within the H-Blocks of HMP Maze.

HMP Maze, formerly known as Long Kesh, and still referred to by that name by Republicans, was the high-security prison west of Belfast where most of the paramilitary prisoners were held. The first and largest group consisted of mainly Belfast Republicans in favor of dropping abstentionism.

The second group, relatively influential outside the prisons but tiny in the H-Blocks, was supportive of the outside faction headed by older, Southern Republicans.

There were three broad factions among IRA prisoners: those supportive of the leadership, traditionalists who opposed ending abstentionism and left wingers.

This group represented the staunch advocates of abstentionism but was weakened by the departure of Ruairí Ó Brádaigh from the position of President of Sinn Féin in 1983. The third group was a bunch of leftwing prisoners headed by Tommy McKearney. The latter campaigned for a Marxist orientation and the formation of syndicalist Trade Unions. They later formed the short-lived League of Communist Republicans.

In 1985/86, the first position was already the dominant one in the movement, both inside and outside the prisons. Nonetheless, some IRA volunteers leaned towards the second faction because they opposed parliamentarism. Among them were members of the East Tyrone Brigade, in Northern Ireland, and other areas like County Monaghan or North Louth, both in the Republic of Ireland. These areas were important pieces of the IRA’s war effort.

The East Tyrone Brigade was one of the most active and effective units of the Provisionals at that time. One of their members, Jim Lynagh, who was killed in an ambush at Loughall in 1987, had actively campaigned among IRA prisoners against the dropping of abstentionism during his five-year spell in Portlaoise Prison, the Republic of Ireland’s high-security prison.

While these people were also a minority in the Northern IRA, established IRA members like Lynagh could have given the increasingly isolated pro-abstentionist faction in the South a more militant outlook. To be sure, the abstentionist Southern Republicans were portrayed as ageing politicians by the younger anti-abstentionist Northerners. The support of militants for the pro-abstentionist faction would not have changed the outcome of the split in 1986, but it could have made it more damaging for the Provisionals.

In order to weaken the possible damage of the split, the rank-and-file volunteers and the prisoners had to be won for the electoral strategy by taking the bread out of the mouth of the abstentionists. It is at this point that the idea of an “Irish Tet offensive” comes into play.

The Irish Tet

Journalist Ed Moloney writes that “the IRA in 1986 was in the midst of organizing a military venture which, if successful, might have had as much a sickening effect on British public opinion [as a Royal assassination].”

He continues:

“By 1986 the IRA was well advanced in planning and organizing a massive military offensive, nicknamed an IRA ‘Tet’ by some, using Libyan-supplied weapons and explosives as well as cash. Like the effect of the Vietcong’s ‘Tet offensive’ of January 1968 on American public opinion, the IRA’s campaign was intended to weaken British resolve to continue fighting in a war it no longer had belief in winning or ending.”

In the 1980s, the Provisionals re-established close links they previously held in the early 1970s with the Libyan regime of Muammar Gaddafi. Gaddafi provided the IRA with plastic explosives Semtex, Millions of US-Dollars and various kinds of arms such as its first RPG-7 rocket-propelled grenade launchers.

The promise of a major military escalation helped to convince many IRA members to support the Adams leadership and their political project.

In autumn 1987, the biggest cargo on board the Eksund was intercepted and the plans for an “IRA Tet offensive” vanished. Nonetheless, it had a lasting impact on the Republican prisoners. The rumours that the launch of the Tet-like offensive was imminent was taken as evidence by the majority faction that the dropping of abstentionism did not mean a road to parliamentarism. Instead, a large-scale military assault on the British army would be accompanied by election campaigns.

In an interview with me in his flat in West Belfast on 28 July 2015, Gerard Hodgins, a Republican prisoner in the H-Blocks at that time, remembers:

“In 1986, most people followed [Gerry] Adams because there were rumours that we were going to have a ‘Tet offensive’ like the Vietnamese and there were rumours that a lot of gear was coming in. We hadn’t actually got it yet, we hadn’t got the Libyan gear. It was not there for use, but the plan was supposed to be that when the Eksund was coming – the one that was caught – the gear would come North immediately, and have it and we just shoot, attack everything and sustain it for as long as possible.

We accepted we’d have a lot of casualties because it was going to be a different kind of warfare, but we were up for it. That was why Adams could carry the whole movement, he was promising, on the one hand, we were driving them out because we finally had the international connections and the gear and that’s how he carried them. Even I voted for abandoning the abstentionism because I saw it as a political obstacle.”

Over the past decade, journalists and historians discussed the chances for success of an “Irish Tet offensive” if the Eksund would have made it to Ireland. We do not know and discussing it is a fruitless attempt at counterfactual history. Indeed, the biggest impact the “Irish Tet offensive” had, was the myth it created among the prison population.

In the late 1980s, many Republicans naively thought that military victory was on the horizon and with the electoral support that had grown since the hunger strikes, the British army could be driven from Northern Ireland, the island of Ireland finally reunited, and their own Irish Cuba established off the coast of Britain. It was this vision that brought them to support Gerry Adams.

Socialism in the H Blocks

To be sure, it was not only the name used for these plans by the IRA, “Tet offensive,” that resembled admiration for the North Vietnamese Forces.

Irish Republican prisoners were familiar with the Vietnamese struggle since becoming in contact with anti-imperialist literature in the internment camps and prisons during the 1970s and 1980s. Among other literature like Frantz Fanon, Che Guevara, and Antonia Gramsci, prisoners read Ho-Chi Minh and General Giap.

In an interview with me on the 31 March 2014, former IRA prisoner Anthony McIntyre remembers about his time in the Long Kesh internment camp:

“There were all these documentaries about Communism and Chile, Cambodia, Khmer Rouge, Vietnam and they all were reading General Giap, Che Guevara, [and] discussing strategy. I thought they loved it, there was a lot of talks. Some of these people were very committed and they wanted to learn more and Adams held a strong IRA commitment in there. And they held a strong anti-leadership position in there. They thought that the [Southern based] leadership should be overthrown and they were talking left-wing.”

Left wing IRA prisoners were dismayed by the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

In the prisons, the IRA prisoners organized their own classes and reading groups. Influenced by Marxist and anti-imperialist literature they became fascinated by guerilla struggle, the Cuban revolution, and Mao’s long march. In Vietnam, a guerrilla army had fought the militarily much more advanced United States to its knees.

For many Republicans, the situation of the North Vietnamese was similar to their own in the fight against the British Army. Hence, the “Tet offensive” became their beacon. However, the illusion of the Irish Republican prisoners was soon crushed by another international event: the fall of the Berlin wall.

The fall of the Berlin wall was a dramatic event for the Republican prisoners. Over the previous seven to eight years, the prisoners had developed their own interpretation of “Socialism” and the events in Berlin, the fall of the Soviet Union, and, what they considered the defeat of their newly found international allies, made no sense to them. Danny Morrison, in an interview with me in his Andersonstown house on 28 July 2015, says that

“I do think when the [Berlin] wall came down in Germany in 1989, a lot of them got their eyes opened and there was a move away from this purist ideological approach to a more pragmatic form of politics.”

The South African example

The Berlin wall had fallen and removed the illusion of a Socialist future from the Republican prisoners. At the same time, the conflict in Northern Ireland started to wind down and the peace process gained momentum. In this situation, the prisoners were looking for new guidance and new ideology to understand the world.

Once again, as the fall of the Berlin wall, it was an international event that had a lasting impact on the political views of the Republican prisoners. Only months after the collapse of the GDR, on 11 February 1990, ANC leader Nelson Mandela was released from prison.

Nelson Mandela was in many ways a role model for Republican prisoners in Ireland. He was a freedom fighter, he fought injustice and discrimination. To be sure, a similar social, cultural, and political oppression the Catholics felt in Northern Ireland was fought by Mandela on behalf of Black Africans, but, moreover, he had served a long sentence such as most of the Republican prisoners sentenced after 1976. For many prisoners, an end to the conflict and a release from prison was possible by following Mandela’s example.

Following Nelson Mandela’s example meant accepting compromises, and preparing prisoners for compromise by unchaining them from radical thinking and embracing pragmatism and the peace process.

Yet, for most of the Provisional prisoners, following Mandela’s example meant accepting compromises, and preparing prisoners for these compromises following years of waiting for an “Irish Tet offensive” meant unchaining them from radical thinking and embracing pragmatism and the peace process.

The 1970s and 1980s were characterised by a turn to left-wing literature and understanding of the prisoners. While the idea of an “Irish Tet offensive” never materialised, it created a myth that, ultimately, served the purpose of facilitating the departure of the Irish Republican movement from armed struggle to parliamentarism.

Instead of building a united democratic Socialist Republic, they entered the newly created Northern Ireland Executive, a regional government, in a coalition with their Unionist opponents in Stormont – in a still divided island. Despite the hopes for an “Irish Tet offensive” and revolutionary sentiments in the H-Blocks, it was only because of the support of the IRA prisoners that this process was successful and, thus, Gerard Hodgins looks back and asks himself: “It’s only when you look back, you recognise this in hindsight. You look back and you say to yourself: How the fuck did I not notice?”

Dr Dieter Reinisch is a Historian at the European University Institute in Florence and Editorial Board member of the journal “Studi irlandesi: A Journal of Irish Studies” (Florence University Press). He teaches History and Gender Studies at the Universities of Vienna and Salzburg. He tweets on @ReinischDieter and blogs on me.eui.eu/dieter-reinisch.