Today in Irish History, 31 July 1922 – Harry Boland is killed

By John Dorney

On July 31, 1922, men in the green uniform of the Irish Free State entered the Grand Hotel, in the seaside town of Skerries, north of Dublin. They were looking for Harry Boland, an anti-Treaty Republican activist, embroiled by now in Ireland’s bitter civil war over the Treaty.

According to one Republican activist, they were out to kill him, ‘as Harry had been very active in trying to bring about a reconciliation between the two sides and had been meeting Mick Collins for that end.’[1]

Harry Boland and Michael Collins had indeed been close friends and colleagues prior to the split over the Treaty. But Collins was now commander in chief of the Free State’s National Army and Boland was now quartermaster of the anti-Treaty IRA Dublin Brigade. With Boland at the hotel in Skerries was Joe Griffin, the IRA’s Director of Intelligence.

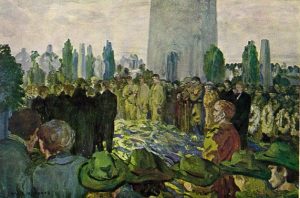

Harry Boland was shot by Free State troops at hotel in Skerries in July 1922

It is not exactly clear what happened when the Free State troops burst into Boland’s and Griffin’s hotel room. According to the Irish Times, Boland was ‘shot while resisting arrest and was hit in the right abdomen.’ [2] Some reports suggested that Boland tried to seize the gun of one of the arresting soldiers and then ran down the corridor of the hotel to get away. The troops, according to this account, fired two shots in the air and then one, the fatal one, to his body.[3]

He died two days later in St Vincent’s hospital Dublin. Joe Griffin was arrested unharmed.

Who Was Harry Boland?

Harry Boland was born, like many nationalist revolutionaries of his generation, into Dublin’s lower middle class, in the northside suburb of Phibsborough. He followed a familiar trajectory through the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Easter Rising of 1916 into gaol at the high security prisons of Dartmoor and Lewes. On his release he threw himself into political activism with Sinn Fein, for whom he was elected TD for south Roscommon in the historic election of 1918.

In 1919 he and Michael Collins only narrowly escaped arrest when the rest of the members of the underground Dail government were imprisoned by the British. The two worked closely together thereafter in Dublin, raising money for the ‘Republican loan’ a system of voluntary taxation that kept the rebel Republican government afloat.

During the struggle for Independence, Boland worked with both Michael Collins and Eamon de Valera, mainly in raising funds for the Irish Republic.

Later in 1919, Boland was nominated by Eamon de Valera the President of the Republic, as special envoy to the United States. While, in the popular film Michael Collins this is depicted as a Machiavellian move by de Valera to weaken Collins’ control over the movement, it can equally plausibly be seen as a logical extension of Boland’s fund raising activities in Ireland.

And while de Valera himself returned from the United States in early 1921, Boland in fact stayed there, coordinating Irish Republican publicity, fund raising and – more secretly – arms purchasing and smuggling until early 1922.

Treaty and peace efforts

By then, all had changed utterly. Collins and his colleagues had signed the Anglo Irish Treaty, de Valera and his followers had refused to accept it. The movement was split from top to bottom

Boland was from the start adamantly against the Treaty which he viewed as surrender of the Irish Republic they had declared in 1919. He was recalled from America to participate in the Treaty debates, where he declared, ‘I rise to speak against this Treaty because, in my opinion, it denies a recognition of the Irish nation…

I object to it on the ground of principle, and my chief objection is because I am asked to surrender the title of Irishman and accept the title of West Briton. I object because this Treaty denies the sovereignty of the Irish nation, and I stand by the principles I have always held— that the Irish people are by right a free people. I object to this Treaty because it is the very negation of all that for which we have fought.’[4]

The Treaty was carried in the Dail but de Valera and his followers, including Harry Boland, walked out in protest. This might not by itself have been fatal to Irish nationalist unity as, after some persuasion de Valera re-entered the Dail.

What was more fatal was that in a convention of March 1922, the majority of the IRA the guerrilla army of the Republic, voted to refuse to accept the Treaty. Harry Boland attended the convention as representative of the Dublin Brigade.

Though adamantly against the Treaty, Boland tried to prevent Civil War.

Despite his friendship with Collins therefore, Boland was a militant anti-Treatyite. However, he also attempted to prevent the outbreak of Civil War.

As early as March, 1922, Boland, proposed a stop to public meetings by either side and to ‘get Dev, Collins, [Arthur] Griffith and [Cathal] Brugha on one platform on the Ulster Situation’ [i.e. to try to unify them on the one matter they agreed upon, Irish unity and the end of Northern Ireland]. They were to campaign together in the first Free State election ‘with a certain percentage of seats allotted to them’ [the anti-Treatyites].

Richard Mulcahy, by that time Free State military Chief of Staff, agreed in principle if Boland ‘could get Dev and Cathal [Brugha] to agree’.[5] In a number of meetings in May, an agreement was patched up along these lines between Collins and de Valera, and it was agreed that the ‘general lines of the constitution’ of the Free State would be agreed upon.

While this helped to ensure a fairly peaceful election in June 1922, the pact did not hold. The pro and anti-Treaty wings of Sinn Fein ultimately fought the election as hostile parties. After the pro-Treaty victory, Collins and his colleagues came under increasing pressure from the British to attack the anti-Treaty IRA garrison in the Four Courts in the centre of Dublin.

After a series of provocation by both sides – the arrest of anti-Treatyite Leo Henderson and Free State general Ginger O’Connell – Collins’s forces did indeed open fire on the Four Courts on June 28 1922 and Civil War did indeed break out throughout the country.

Civil War and death

Whatever Boland’s peaceful intentions may have been before the Civil War broke out –and it appears as if he did all he could to avoid a violent confrontation – he seems to have become a determined participant in the Civil War thereafter.

He participated in the fighting in Dublin city from June 28 to July 5 1922 and thereafter in some skirmishing near Brittas along the Wicklow- Dublin border.

And even after the Republican defeat in that battle he seems to have been determined to wage guerrilla war on the Free State.

He saw, as many anti-Treatyites did, the Provisional Government of the Free State and the temporary ‘war council’ set up by Collins, comprising himself Richard Mulcahy and Eoin O’Duffy, as a military dictatorship. In a letter of July 27 Boland wrote that ‘dictatorships is [sic] now the rule’ and that ‘Mick, Dick and Owney… have attempted to usurp the function of parliament.’ [6]

His enemies, though, were beginning to close in on him.

On July 28 1922, detectives from the Free State’s Criminal Investigation Department (CID) raided the Republican political headquarters on Dublin’s Suffolk Street, where they arrested senior anti-Treaty TD Sean T O’Kelly [later to serve as President of Ireland].[7] He had on him a letter from Harry Boland, now serving as Dublin IRA Quartermaster, asking O’Kelly to go to America and re-establish contact with Clan na Gael, the Irish American affiliate of the IRB and to bring back weapons and ammunition.

At the time of his arrest Boland was trying to import large quantities of weapons and ammunition into Ireland from America.

If Boland was trying to make peace at this point there is certainly no sign of it in this correspondence.

Boland wrote, ‘This fight is likely to be long drawn out and we shall require money and material … Bring back Thompsons [submachine guns] revolvers, .303, .45 [ammunition] etc.’ Come to 31 Richmond to talk, 6 pm. HB’.[8]

Collins refused to allow the closure of the Republican offices on Suffolk Street, despite the arrest there – ‘we are not out to suppress political opinion’, he wrote to WT Cosgrave, but did order the arrest of Boland. [9]

Boland was located two days later in a hotel in Skerries and during his arrest was shot and mortally wounded.

He is often counted as the first of what would be many targeted killings of anti-Treaty fighters in Dublin. [10] However there is reason to believe that his killing was not in fact an assassination but rather a botched arrest.

Republican historian, Dorothy Macardle, later wrote that his shooting was not premeditated. ‘The soldiers who shot him seemed unaccustomed to firearms and distressed by what they had done’.[11]

Michael Collins seems to have regretted his friend’s death very much. He wrote to his fiancée Kitty Kiernan, “I passed Vincent’s Hospital and saw a crowd outside. My mind went in to him, Harry lying there dead and I thought of the times together . . . I had sent a wreath. Nevertheless, I suppose they would return it torn up.”[12]

Meanwhile Ernie O’Malley, head of the IRA Eastern Division reported unemotionally to his Chief of Staff Liam Lynch:

The arrest of senior officers has generally played havoc with this command. Harry Boland who is acting QM [Quartermaster], and the D/I [Director of Intelligence Joe Griffin] have been arrested last night. Harry was shot through the spine and stomach … Michael Carolan Adjutant of 3rd Northern Division [Belfast] … was wounded on Grafton Street. They seem to be concentrating on officers. The result will be that the Brigade here will be without officers.[13]

The thousands of arrests – O’Malley himself was to be caught about three months later – did indeed ultimately cripple the anti-Treaty IRA’s campaign.

Boland’s life and death, at the age of just 38, have been popularised by Neil Jordan’s 1996 film Michael Collins, which used the device of the friendship between Boland and Collins to show the tragedy of the Treaty split and the Civil War.

For all the film’s dramatization and simplification – for instance it has Boland being shot in a sewer in the aftermath of the Four Courts battle – there is a note of genuine pathos in the deaths of Boland and then his former friend Collins just four weeks later in County Cork.

Harry’s brother Gerald later became a senior minister in the governments of Eamon de Valera’s Fianna Fail in the 1930s and 40s. During the Second World War Gerald Boland used emergency legislation to crush the IRA of that era. His son Kevin, a Minister in the 1960s, took a strong republican position on the crisis in Northern Ireland that erupted in 1969-70 and resigned over the Arms Crisis of 1970.

References

[1] Eileen McGrane BMH WS 1752

[2] Irish Times August 25, 1922

[3] Irish Times, August 5, 1997

[4] Dail debates 7 Jan 1922, https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1922-01-07/2/

[5] Mulcahy Papers UCD P7/B/192.

[6] Report on arrest of Seán T O’Kelly, submitted 11/8/22 Mulcahy Papers UCD P7/B/4.

[7] Report on arrest of Seán T O’Kelly, submitted 11/8/22 Mulcahy Papers UCD P7/B/4.

[8] Captured letter Boland to O’Kelly27/7/22 Ibid.

[9] Captured letter, Boland to O’Kelly 27/7/22, ibid.

[10] The Last Post, p. 136.

[11] Macardle, The Irish Republic, p. 709.

[12] Irish Times August 5, 1997

[13] Ernie O’Malley to Liam Lynch, 31 July 1922, in Dolan and O’Malley, No Surrender Here!, p. 80.