Book Review: The Dublin Docker: Working Lives of Dublin’s Deep-Sea Port

By Aileen O’Carroll and Don Bennett

By Aileen O’Carroll and Don Bennett

Published by Irish Academic Press, 2017.

Reviewer: Jim Dorney

Dockers were a significant part of Dublin’s working class both in terms of numbers and reputation. This book tells the story of their working life, family life, and social life, warts and all. The book was compiled using interviews and reminiscences by dockers themselves and from Port records.

Dock labour was marked by insecurity and uncertainty of employment, and a degrading method of selection for work. The method of selection was known as the “Read”. Each morning a group of men seeking work gathered in the open. Above them stood a foreman who selected those who would work that day, by calling out the names of the fortunate. Those not called were destined for unemployment.

This book tells the story of the Dublin dockers’ working life, family life, and social life, warts and all.

Docker competed with docker at the read, jostling and shoving to get noticed by the foreman. One docker described the “read” as a Me Fein affair. Employment prospects were however improved by leaving a drink for the foreman in the pub ,the evening before the read , or by passing money ,hidden in a match box while drinking.

To combat this harsh system, a Trade Union list of full time dockers was drawn up, those on it to be employed as a priority and before all others. These men were known far and wide as button men. They were identified by wearing the appropriate button on their belt.

The work when it was secured was punishingly hard, working in dust filled holds, shovelling coal and grain with specialised shovels. [Giving inspiration to the song ‘dont forget your shovel if you want if you want to go to work’].

Work on the docks was usually casual and often punishingly hard.

Diverse cargoes; wood ,chemicals, ore, newsprint, tea and fancy goods, all required specialised knowledge to unload. A diverse range of Dockers were employed to do the unloading, Crane men, Pushers off , singers out checkers etc., each with their own expertise. It was dangerous work and accidents did happen.

Michael Donnelly a Docker trade unionist said in 1998 “to my knowledge we had quite a few deaths, around 20. When something goes wrong it is serious”. Despite the harsh conditions, dangers and indignities involved, dockwork became a tradition amongst families with father following son onto the docks. When they did work, the money was good.

To combat the insecurity and poor conditions dockers embraced trade unionism. Most followed Jim Larkin and joined the I.T.G.W.U. they were the backbone of that Union. They again followed Larkin when he split from the Transport Union to form the Workers Union of Ireland in 1924.The port was split from end to end by rivalry between the two Unions. Eventually tired of the bitter inter Union rivalry, a new Union the Irish Seamen and Port workers Union was formed, later renamed the Marine Port and General Workers Union.

Despite all the division, the interest and welfare of dockers was advanced. Following a protracted strike, a 40 hour day week was achieved in 1966 without loss of pay. The button system led to decasualising for many, giving those covered a guaranteed income even when work was not available. In return for decasualisation, dockers agreed to lift their five year opposition to containerisation, this led to the death knell of the docklands and dockers in the traditional sense.

Containerisation led to the death knell of the docklands and dockers in the traditional sense.

Home life was centred mainly in dockside tenements, cramped accommodation, outdoor toilets ,communal taps, heating by open fires. Families were large with wives staying at home to mind the children. Children often worked to supplement family income. Major rehousing took place to the suburbs (Beaumont, Cabra ,Inchicore, Kilmanham) to alleviate the poor living conditions. Despite these improvements many criticised the move for breaking the strong community spirit, sending families outside the canals to “culchie land”

Casual labour led to variable daily cash-into the hand payments for dockers. Very often the dockers hid their true income from their wives. Regular employment led to fixed incomes, known to wives, much to the chagrin of the dockers.

Cash into the hand payment each day led to the temptation to visit pubs on the way home from work. According to one docker, this system led to a situation where ‘every day was Saturday’ on the docks. Dockers saw their role as that of breadwinner, which absolved them from responsibility for running the home. They saw the pub as their refuge. No such refuge was allowed to their wives.

The dockers’ morning tea break was also a temptation with three to four pints being consumed, it was nicknamed ‘the beero’.

Another topic dealt with in the book was pilfering from ships, which was a feature of all docklands, Dublin being no different. Examples given by O’Connell and Bennett include two combine harvesters beng stolen in 1964 and 100 barrels of nickel weighing 254 kilograms in 1970. Most Pilfering was on a much lesser scale. However it was also emphasised that some dockers never took anything. For those caught the penalty was suspension for the first offence, prosecution and sacking for repeated offences.

The book is wide ranging in its scope, seeking to show how dockers lived. It is compiled from interviews and reminiscences from dockers themselves.

Dockers had a culture and moral code of their own. To the outsider dockwork was not a respectable profession. Dockers were denied access to many private venues. Attempts to form their own social club foundered on the failure to agree a venue due to the intense north-south side rivalry. In the view of the authors the only acceptable venue would have been an island in the Liffey!

Solidarity was the sine qua non amongst dockers. The unforgiveable breach of this code was strike breaking, or scabbing. Scabs were shunned, isolated and boycotted, not only themselves, but their families and descendants.

The book is wide ranging in its scope, seeking to show how dockers lived. It is compiled from interviews and reminiscences from dockers themselves. In that context one should be conscious that truth never got in the way of a good story, a fact acknowledged by the authors. This leads to a colourful and basically sound picture of life on the docks, but readers should approach some tales with scepticism.

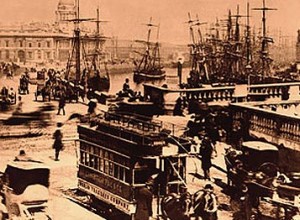

Tribute is paid by the authors to the dock workers preservation society set up in 2011, to preserve the rich history of the dockers and their community. The book has a wealth of photographs, which illustrate graphically the vanished world of the docks. The flavour of the book and of the people profiled in it can be summed up by the quotation in chapter seven, ‘dockers don’t see it as an occupation, they see it as a way of life’.

The decline of employment in the north inner city due to containerisation , has created a vacuum which are tragically evident in many social problems that we see in that area today .

Jim Dorney is the former general secretary of the Teachers Union of Ireland.