Revisiting the Red Cow Murders, October 7, 1922

New evidence on a disturbing killing during the Irish Civil War. By John Dorney.

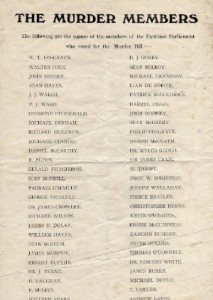

On October 7 1922, in the middle of the Irish Civil War, three young anti Treatyites Edwin (or Eamon) Hughes (17), Brendan Holohan (17) Joe Rogers (16) were arrested by National Army troop under Charlie Dalton in the Dublin suburb of Drumcondra. They were in the act of putting up posters calling for the killing of ‘Free State forces’ … ‘the murder gang also known as military intelligence and so-called CID men’.[1]

The following morning their lifeless bodies were found at the Red Cow townland, south west of Dublin city. Hughes and Holohan had been shot four times each. Rogers, who seems to have tried to get away, was found some distance away from the others, shot sixteen times.[2]

Three young anti-Treatyites were arrested and later found shot dead and dumped at the Red Cow, outside Dublin.

It was one of the most distressing atrocities of a dirty, internecine war in Dublin. The Freeman’s Journal lamented ‘hardly a week goes by without some ghastly incident … proof of the demoralisation of the nation, where is it all to end?’ [3] The Irish Independent called for the killers to be ‘brought to justice’ and urged the public to come forward to aid in ‘putting a stop to this lamentable unchristian state of things.’[4]

I wrote in my recent history of the period, The Civil War in Dublin of the incident, ‘These were particularly callous killings. Aside from the youth of the victims, the boys had been unarmed and had posed no physical threat to the troops who captured them.’[5]

However, a new batch of pension records was released to the public by the Military archives this October has shed some new light on the case.

Eamonn Hughes and Brendan Holohan

Eamonn (born Edwin) Hughes was 17 at the time of his death and lived with his parents at 107 Clonliffe Road in Drumcondra in Dublin’s northern suburbs. The family were members of the city’s respectable lower middle class.

His father was a clerk in the Department of Industry and Commerce and his mother was a music teacher. They, according to Eamon’s bother Gary, ‘always facilitated their son’s aspirations in spite of the danger and home disturbance.’ Eamonn himself was an apprentice dentist.[6]

His parents appear to have been devastated by his death. His mother seems to have suffered from a breakdown, could no longer teach music classes and according to her doctor, no longer felt able to leave her house. His father also developed chronic heart problems within two years of his son’s death. By 1933, when, with Fianna Fail in power, anti-Treatyites could apply for pensions, they were described as ‘practically destitute’.

Eamonn Hughes joined the Republican youth wing the Fianna in December 1920 and in May 1921, just two months before the Truce with the British, transferred to the IRA proper, where he was used as a scout. His direct superior in the Dublin Brigade, IRA 2nd Battalion, Michael Murphy, testified that he was a ‘sergeant’ (a term not usually used in the IRA) despite his young age and was ‘of excellent character.’

Murphy stated to the Pensions Board in 1933 that, ‘while acting under orders he was arrested by Free State troops on Clonliffe Road. He was armed at the time’. [7]

A statement, just made public, by Hughes’ IRA officer to the Pension Board, says he was armed when he was arrested.

Brendan Holohan, one of the other boys killed Red Cow, was ‘Truce’ Volunteer, joining the IRA in April 1922, just as the guerrilla army was splitting apart over the Treaty. His background was very similar to that of his friend Eamonn Hughes, he was of lower middle class stock, from the northern suburbs of Dublin and was employed as County Clerk.

His Battalion Officer Commanding Tom Burke, stated that when he was arrested he was ‘on an intelligence patrol’.

Joe Rogers (the third victim)’s family do not appear to have filed a pension request.

The Pensions Board concluded in the case of both Hughes and Holohan, ‘His body was found riddled with bullets at Red Cow, Clondalkin, Co Dublin… The Board, from confidential inquiries made, are satisfied that his death was a s a result of his activities with Oglaigh na hEireann (IRA)’. [8]

This information then, while in no way lessening the tragedy of the deaths of the three teenagers, or excusing their killers, does complicate the story of three innocent boys shot for putting up posters. Thus, it is worth looking at the case again.

The facts of the case: ‘Murdered and thrown in a ditch’

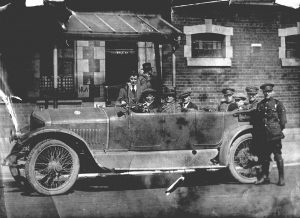

On 7 October 1922, Charlie Dalton (Deputy head of National Army Intelligence, along with Nicholas Tobin (brother of Liam, Army Director of Intelligence) and a driver Feehan, on a routine patrol, picked up Hughes Holohan and Rogers in Drumcondra, close to their homes.

At the inquest, the court was told that three had agreed to take over the job of postering from Jenny O’Toole, a local Republican girl, due to her being abused by the public. ‘She had mud flung at her’ as well as verbal abuse. The boys carried copies of the underground anti-Treaty newspaper, Poblacht na hEireann, and the posters allegedly called for the killing of ‘Free State forces’ … ‘the murder gang also known as military intelligence and so-called CID men’.[9]

It is not clear how this story squares with the testimony to the Pensions Board that one of the young man was armed and that they were on an ‘intelligence patrol’. If both things are true then them taking over postering as well was the height of foolishness.

One can imagine the rage of Dalton and Tobin upon reading the incitements to kill them and their colleagues. This combined with finding Hughe’s revolver might have sealed their fate. However, the youths were not killed on the spot, but formally taken prisoner and, along with a couple of other prisoners picked up on Harcourt Street, were driven back to Wellington Barracks, headquarters of Army Intelligence.

The three boys were taken into custody at Wellington Barracks, where troops stated they were questioned for twenty minutes and let go. They were never seen alive again.

There, Dalton later testified, they were handed over to fellow veterans of pre-Truce IRA Intelligence, Seán O’Connell and James Slattery, now both Military Intelligence officers. A Captain Corrigan testified that the three boys were released after twenty minutes, having been interrogated by an officer named Seán Murphy.[10]

The following day, a National Army patrol from the Tallaght Camp found their bodies in a quarry near Clondalkin.[11] Someone had driven them from Wellington out to the quarry, near the Red Cow townland and shot them dead.[12]

The Naas Road area was where at least four other anti-Treaty prisoners were also assassinated during the Civil War. The suspicion then and ever since, was that Charlie Dalton the arresting officer had ordered their deaths. This, it was never possible to prove.

Among all the anonymous killings taking place at the time, the Red Cow murders were very unusual.

As the victims were first formally taken prisoner and logged at Wellington Barracks, National Army officers were identified by name at the Inquest, where Republican counsel Michael Comyn called on the jury to reach a verdict of wilful murder against Charlie Dalton, who could then be charged with the killings. Dalton was briefly placed under arrest by the Criminal Investigation Department or CID.

The inquest though became something of a farce, with stonewall obstruction by the Army personnel and both Comyn and Tim Healy, the barrister representing Charlie Dalton, using it as a platform for the partisan position of their employers in the Civil War. Michael Comyn, cross examining an un-cooperative National Army officer was told: ‘the Black and Tans didn’t make me answer and you won’t’ – refusing to give a list of prisoners taken at Wellington Barracks that night.

Comyn replied with bluster: ‘you are one of the King’s officers are you not?’ You were in the ‘cease-to-do-evil’? [Wellington Barracks[13]] You do know that Poblacht na hEireann [the anti-Treaty newspaper] is sold in shops don’t you?’

When Comyn pressed the officer as to whether he had told the court everything that had happened in the Barracks that night, Healy instructed the unnamed officer: ‘do not answer.’ Healy argued ‘there was no inquest on Michael Collins’. To which Comyn replied ‘he died like a soldier, he died in battle.’ His colleague Mr Black added: ‘he was not murdered and thrown in a ditch.’[14]

National Army officers refused to answer questions at the inquest which judged that the youths were killed ‘by persons unknown’.

Summing up his own case Healy objected that, ‘you would think the country was not in a state of war and the three were harmless.’ He alleged that Charlie Dalton stood accused only because his brother Emmet was a senior National Army commander. He continued that it was the anti-Treaty side that had started the Civil War and who, he asked could now ‘set a boundary to the march of extermination?’ ‘Was it surprising that three members of the Republican Army were found dead?’ he asked.

Whether Dalton personally gave the order to kill Hughes, Holohan and Rogers, in the absence of witnesses who were willing to talk, it was impossible to prove. The jury at the Inquest ruled that the three Fianna boys were ‘killed by gunshots fired by persons unknown.’ Dalton was back at his duties as head of Eastern Command Intelligence by late November.

Nicholas Tobin, the other arresting officer, was killed shortly afterwards in a raid on an anti-Treaty bomb making factory on Gardiner Street, apparently shot accidentally by his own troops.[15]

Making sense of the killings?

None of this, however, quite explains why the Red Cow killings occurred. Why would anyone gun down three harmless youths for putting up posters?

In light of the new evidence we now have from the anti-Treaty IRA, we now know that Hughes may well have been armed on the night and Holohan was ‘on an intelligence patrol’. A CID officer named Charles Murphy alleged at the inquest one the three boys was carrying a revolver, and we now know that this was possibly true.

It might help to explain the subsequent killings somewhat, along with the bloodthirsty calls for the shooting of Free State officers on the posters they were putting up, but in some ways it raises more questions than answers.

In September 1922 the Provisional Government of the Irish Free State had passed emergency legislation allowing for the execution of anyone founding possessing arms or ammunition ‘without the proper authority’ or ‘aiding and abetting attacks on state forces’. So if Hughes was carrying a revolver and if the other two boys could be shown to be aiding him they were certainly liable for internment if not (due to their age) execution by firing squad.

If Hughes was indeed armed at the time of his arrest, he could have been legally tried and executed by military court.

And yet, puzzlingly, Army officers testified at the inquest that they let the three prisoners go after twenty minutes’ questioning. Nor was the revolver that they allegedly took from Hughes ever produced.

So why illegally shoot three teenagers who could have been quite legally tried by military courts anyway?

One possible reason was that the National Army Intelligence, aware that the anti-Treaty IRA was topping up its depleted manpower by mobilising the Fianna, was intent on terrorising that organisation into quiescence. Fianna leaders Sean Cole and Alfred Colley had been among the first assassinations of anti-Treatyites in Dublin in August 1922.

Frank Sherwin, a Fianna member captured after an attack on Wellington barracks in November 1922, was also brutally beaten there by Intelligence officers Joe Dolan and Frank Bolster and subsequently by Charlie Dalton in Portobello Barracks in an effort to get the name of his OC, Charlie O’Connor.[16]

It could be that the killings were simply the result of loss of temper, or drunken rage by young men who were, by this time, behaving in a very unstable, violent and erratic manner.

There seems to have been a particular personal animus against the Fianna on the part of pro-Treaty troops. In part this might be explained by the resentment against young ‘Trucileers’ who had not fought the British but were now prolonging pointlessly, in the pro-Treaty view, the Civil War.[17]

Dalton and his comrades, or whoever killed the three teenagers, were no doubt were filled with rage at the thought of one of their men dying at the hands of young boys who had never fought ‘the common enemy’. Already, hundreds of National Army soldiers had been killed in the war over the Treaty, some no doubt killed by youths as young as those who died at the Red Cow.

But it could be that the killings were simply the result of loss of temper, or drunken rage by young men who were, by this time, behaving in a very unstable, violent and erratic manner. They might have decided that a formal military court might have let the youths off as a result of their age and decided to dispense with formalities.

Much the same group of officers who were behind the ‘Murder Gang’ was also responsible for the widespread abuse of prisoners, especially at Wellington Barracks.[18] Up to twenty five anti-Treaty prisoners were killed by ‘persons unknown’ in Dublin during the Civil War, and over 100 nationally.

Not long after the Red Cow killings, Richard Mulcahy the Army Chief of Staff removed Charlie Dalton, Liam Tobin and many of the other pre-Truce IRA Intelligence officers from their positions directing Army Intelligence, citing their clannishness, secrecy and unwillingness to take orders from the Army command. The same group were later behind the attempted Army Mutiny of 1924.[19]

In all wars, reasons are found for the most brutal of killings. In Civil War, the sense of personal betrayal heightens such sentiments. The enemy becomes equated to a parasite within the healthy body of the nation that must be cut out. Anti-Treatyite Sean Lemass (whose brother Noel was assassinated, also by unknown gunmen) said of the Civil War much later, and probably wisely, ‘Terrible things were done by both sides’. ‘I’d prefer not to talk about it’.[20]

In writing about the Red Cow murders, this piece has no wish to stir up Civil War era animosities. No side was wholly innocent, not even the three youths murdered at Red Cow.

While today the Irish Civil War appears merely tragic and futile, during its course, both sides felt justified in doing things they previously would never have contemplated and later surely came to regret.

References

[1] Irish Times, 19 October 1922.

[2] Irish Times, 19 October 1922.

[3] Freeman’s Journal, 9 October 1922.

[4] Irish Independent, 10 October 1922.

[5][5] John Dorney the Civil War in Dublin p.187

[6] Eamonn Hughes Pension File DP4559

[7] Hughes Pension File

[8] DP 4496

[9] Irish Times, 19 October 1922.

[10] Irish Independent, 19 October 1922.

[11] Nation Army Eastern Command Operations reports September–December 1922, Military archives, CW/OPS/07/01.

[12] Irish Times, 19 October 1922.

[13] Wellington Barracks from 1813 up to the 1890s was a prison, Richmond Bridewell, and over the gate was written ‘cease to do evil, learn to do well’, hence the popular nickname, the ‘cease-to-do-evil’.

[14] Irish Independent, 19 October 1922.

[15] Irish Times, 28 October 1922. While it might be tempting to search for a conspiracy in Tobin’s death, accidents and ‘friendly fire’ were all too common in the National Army at this time. Six other soldiers died in this way in Dublin in September and October 1922 alone.

[16] Sherwin, Independent and Unrepentant, pp. 18–21.

[17] Gavin Foster, The Irish Civil War and Society, pp. 23–8, Foster argues that the youth and lack of ‘record’ in the war against the British of many young guerrillas provoked intense resentment on the part of pro-Treaty soldiers and politicians. Equally (pp. 28–9) he argues that the anti-Treatyites were held to be simply ‘young hooligans’. Both of these commonly held assumptions might have contributed in some manner to the Red Cow murders.

[18] See John Dorney the Civil War in Dublin, chapter 16, The Prison War.

[19] See John Dorney, The Civil War in Dublin, Chapters 19, The Wars within the War and 21, Monopolies of Force.

[20] https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/diarmaid-ferriter-after-commemoration-comes-the-hard-part-1.2595340