‘Glorious Madness’ – The Life and Death of Michael O’Rahilly

By John Dorney

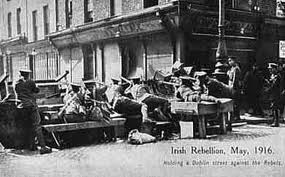

Friday April, 29 1916. The General Post Office in Dublin, occupied on the Monday as the headquarters of republican insurrection, was burning fiercely. The insurgents inside had decided they had to make their escape across Henry Street to the network of small houses and shops on Moore Street.

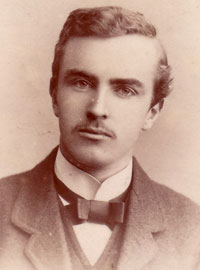

A small party of twenty armed men dashed across the open street to establish a toehold there and to clear out a British barricade. At their head was a distinguished looking gentleman in green uniform, complete with Victorian moustache and sword.

The charging party was hit by volleys of British bullets from the barricades on both sides. Four Volunteers were killed outright. Their leader, the moustached gentleman, fell wounded in the face. He managed to drag himself out of the line of fire to Sackville Lane, where he lay, bleeding, grievously injured. His name was Michael O’Rahilly, better known as ‘The O’Rahilly’.

Michael O’Rahilly was fatally wounded charging British barricades on the Friday of Easter Week, 1916.

It was not until after the insurgents, who had escaped from the GPO to Moore Street, surrendered, over 24 hours later, that O’Rahilly’s comrades, or any help, could reach him. According to Bulmer Hobson, an ambulance driver named Albert Mitchel was the first to come upon him. He had since died of blood loss. Mitchel took his personal belongings including his watch to his sister.[1]

A Prosperous background

Michael Joseph Rahilly, later O’Rahilly and later still (self-styled) The O’Rahilly was born in 1875 making him 41 in 1916, at the time of his death. In many ways he was an odd example of what Patrick Pearse later called ‘the Risen People’.

Michael Joseph Rahilly, later O’Rahilly and later still (self-styled) The O’Rahilly was born in 1875 making him 41 in 1916, at the time of his death. In many ways he was an odd example of what Patrick Pearse later called ‘the Risen People’.

He was the son of a merchant family in Ballylongford, County Kerry. Having also invested in property they left Michael, by adulthood, with an income (very substantial in those days) of £900 per year. [2]

He was educated at Clongowes Wood, the elite Catholic boarding school in County Kildare and subsequently studied medicine in New York. In short Michael Rahilly, as he then was, was the product of the up and coming Catholic upper middle class.

Michael O’Rahilly was the product of the up and coming Catholic upper middle class.

Rahilly married an American woman, Nancy Browne from Philadelphia, in 1900 and the couple had three sons. They lived in New York and then in Paris for a time until they returned to Ireland in 1909. Moving to Dublin, they bought a large house on Northumberland Road, Ballsbridge – then as now one of Dublin’s most desirable addresses – a sure sign that money was not an obstacle for them.

Like many distinguished gentlemen of his generation, the poet W.B. Yeats would be one example, Rahilly was attracted to the ideas of cultural nationalism. According to his sister it was in America that he first developed an interest in the Irish language and immediately on his return to Ireland he joined the Gaelic League. He also bought a house in Ventry on the Dingle Penninsula (in the Kerry Gaeltacht) and employed an Irish-speaking nanny to look after his sons.[3]

First he added an ‘O’ to his surname then he adopted the pseudo-clan chieftain title of ‘The O’Rahilly’.

An indication of his shifting cultural allegiances came in his changing titles. First he added an ‘O’ to his surname bringing it somewhat closer to the original Irish O Rathalaigh, then he adopted the pseudo-clan chieftain title of ‘The O’Rahilly’. The connection to Gaelic clan society was entirely in his own mind (no such title had ever existed before in any case), but he nevertheless appears to have succeeded in getting those in ‘advanced nationalist’ circles to call him by this title.

He was a prominent nationalist in the pre-war years, manager of the Gaelic League newspaper An Claidheamh Solais and a personal friend of Arthur Griffith, the founder of the separatist party Sinn Fein. Among his activities were protesting the visit to Dublin in 1911 of King George V and researching Irish place names at the Ordinance Survey in order to one day change them back from their anglicised forms to Irish. He was involved with Griffith’s party Sinn Fein though never the secret, illegal Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) -he was apparently put off by the Church’s ban on oath-bound secret societies. He did though pen a number of bellicose articles for the Brotherhood’s newspaper Irish Freedom.

Advanced nationalist

In 1912-1914 Ireland was pitched into crisis when Home Rule, or autonomy for Ireland, was blocked by the armed mobilisation of the unionist Ulster Volunteers. In response, nationalists formed their own militia the Irish Volunteers.

Michael O’Rahilly was to forefront of the Volunteers, publishing an article by historian Eoin MacNeill in An Claidheamh Solais calling for their formation and throwing himself into the organisation. He became Treasurer and later Director of Arms. ‘The O’Rahilly’ was not unusual in the generation of 1914 in glorifying militarism. According to his sister Aine; ‘Michael was very keen on having his uniform correct and well finished’.

O’Rahilly was militant enough to reject John Redmond – leader of the mainstream Irish Parliamentary Party but he was not militant enough to be included in the plans of the IRB hardliners

Though his lack of contacts in the IRB must have impeded his access to the inner workings of the Volunteers, he was nevertheless an important figure in the militia. As Director of Arms, he was involved in buying guns for the Volunteers and involved in the celebrated Howth gun running, in which the Volunteers publicly imported nearly 1,000 rifles into Dublin. By 1914 he was routinely followed by ‘G-men’ or Dublin Metropolitan Police detectives, who sometimes also raided his house for arms.

O’Rahilly was militant enough to reject John Redmond – leader of the mainstream Irish Parliamentary Party –and his support for Britain in World War I, and to support Redmond’s ejection and that of his movement from the Volunteers. But he was not militant enough to be included in the plans of the IRB hardliners, Tom Clarke, Sean MacDermott and laterally Patrick Pearse and others (together the Military Council) for an insurrection before the war’s end.

Like his fellow gentleman scholar and Volunteer Chief of Staff Eoin MacNeill, he opposed any armed action by the Volunteers unless it was defensive – a reaction to the British suppression of the movement or the introduction of conscription into Ireland.

So when the secret plan of the Military Council was revealed to the formal leadership of the Volunteers at the last minute on Good Friday 1916, O’Rahilly opposed it and supported MacNeill in trying to call it off.

We see something of his headstrong character in his opposition to the insurrectionists. On Good Friday after hearing that Clarke and MacDermott had had Bulmer Hobson, an ally of MacNeill’s, arrested at gunpoint, O’Rahilly drove to Pearse’s school at St Endas and threatened him with a revolver. Supposedly he told Pearse, ‘whoever tries to kidnap me had better be quicker on the draw’. [4]

MacNeill meanwhile had issued a countermanding order calling off the planned Rising and sent messengers around the country to deliver his orders. Over the next 24 hours O’Rahilly drove (in fact he had a heavy cold and hired a taxi, which must have been expensive) through Cork, Kerry, Limerick and Tipperary on Saturday night to Sunday morning, telling the Volunteer units there not to mobilise and that MacNeill had been deceived. There at least, in his native Munster, he seems to have been effective, as the Volunteers did not stir.[5]

‘Glorious Madness’

Arriving back in Dublin, exhausted and ‘covered in grime’ O’Rahilly assumed the rebellion had indeed been averted. But it had only been put off for a day. On Easter Monday, he was greeted, unexpectedly with the sounds of battle. In the capital the insurrection had gone ahead despite his and MacNeill’s efforts.

In a quixotic gesture, worthy perhaps of his class and generation, he joined the fighting anyway at the rebel headquarters at the GPO. He turned up ‘immaculately uniformed’ and driving his top of the range De Dion automobile.[6] Two famous quotes are attributed to him. “Well, I’ve helped to wind up the clock” he is said to have declared – “I might as well hear it strike!” And just as telling, “it is madness but it is glorious madness”. [7]

O’Rahilly did his best to stop the Rising but joined in the fighting once it broke out and died trying to break out from the GPO.

By the end of the Rising he commanded the top floor of the GPO, having been welcomed back into the fold by the Military Council. He volunteered to lead a desperate charge from the burning GPO to carve out an escape route onto Moore Street. Like officers killed on the Western Front in 1914, he was shot down leading a charge, sword in hand. According to one Volunteer, ‘he had covered only a few yards when he was shot from the barricades and he fell forward, his sword clattering in front of him’.

There is no doubting the bravery of his actions in leading the charge from the GPO to Moore Street, but O’ Rahilly’s death was more agonising than glorious. After being shot he lay for hours overnight alone dying slowly of blood loss. He managed to scribble off a farewell note to his wife and that night was heard crying for water. [8]

According to the ambulance man Albert Mitchel, it was Saturday afternoon before they came upon his body –‘a man in a green uniform on Moore Lane’, and he was still alive. ‘An English Officer’ told them not to load the man onto a stretcher but to leave him where he was. A Sergeant in the Ambulance surmised, ‘he must be someone of importance. The bastards [officers] are leaving him there to die of his wounds, it’s the easiest way to get rid of him.’ At 9 o’clock that evening, Mitchel returned and found the body, now dead, still guarded by officers, he was later told it was The O’Rahilly.[9]

Michael O’Rahilly was buried in Glasnevin cemetery. His two sisters and their friend Austin O’Donoghue were the only people at the funeral.[10]

References

[1] For the action where O’Rahilly was killed see Micheal MacDonnacha, An Phoblacht, http://www.anphoblacht.com/contents/21534 for Bulmer Hobson’s statement, http://www.bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie/reels/bmh/BMH.WS0083.pdf#page=2

[2] http://www.1916rising.com/bioORahilly.html

[3] See Aine O’Rahilly BMH http://www.bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie/reels/bmh/BMH.WS0333.pdf#page=1 and Humphreys Family Tree http://humphrysfamilytree.com/ORahilly/the.orahilly.html

[4] Michael Foy, Brian Barton, the Easter Rising p 61Irish Volunteers website articles on O’Rahilly http://irishvolunteers.org/tag/the-orahilly/

[5] Foy, Barton, Easter Rising pp 61-63, 69

[6] Charles Townshend Easter 1916, p158

[7] http://irishvolunteers.org/tag/the-orahilly/

[8] Foy Barton The Easter Rising, p 197

[9] Albert Mitchel BMH http://www.bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie/reels/bmh/BMH.WS0196.pdf

[10] Aine O’Rahilly BMH http://www.bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie/reels/bmh/BMH.WS0333.pdf#page=1