‘Up us!’ – The launch of the Kilmainham Gaol graffiti website.

John Dorney reports on the launch of a new initiative to document the graffiti left by political prisoners at Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin.

During the Irish revolutionary period from 1916 to 1923, as many as 20,000 people were imprisoned at one time or another.

Hundreds of these, including (briefly) the executed leaders of the insurrection of Easter 1916 passed through Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin – the latter on their way to the firing squad in the stone-breakers’ yard. During the War of Independence hundreds more men and women ended up there, along with 22 British Army military prisoners. During the Civil War of 1922-23, it is thought that about 600 prisoners passed through here, the majority of whom were women.

On September 25th 2014, a new website was launched to display the work of a project cateloguing graffiti left by political prisoners in Kilmainham in 1916-24

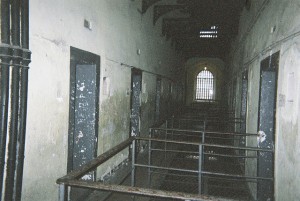

The Gaol which closed in 1924, now stands as public monument both to their experiences and to the history of imprisonment in Ireland. On September 24th 2014, inside the bowels of Kilmainham, a new website was launched, which aims to catalogue the material reminders left by republican prisoners in Kilmainham, in the form of graffiti in the cells, autograph books and other etchings.

You can see the results here http://kilmainhamgaolgraffiti.com/

Etched on the walls of cells in Kilmaniham Gaol are thousands of messages from former prisoners, visible despite as many as 17 layers of whitewash which tried to obscure them.

More than 584 names (393 rendered in English and 154 in Irish) have been recovered from the walls, along with messages ranging from calls for Irish freedom, to celebrations of the IRA or Cumman na mBan fighters on the outside, to feminist demands to simple demands for better food.

Some of the messages are political or militaristic, others are personal and many are complaints about food.

Some messages are religious; such as depiction of the Sacred Heart, but others are critical of the Catholic Church’s failure to support the republicans, especially in the civil war. Other etchings are remarkably carefully drawn portraits of other prisoners. One poem expresses the hope that God will ‘cut the throats of the Free Staters’. One simply says; ‘Up us!’

Pat Cooke of the University College Dublin School of Art History, speaking at the launch of the website, noted that graffiti was almost always written on the wall of the cell door, so that warders could not see it – a subtle attempt to regain some personal autonomy by the prisoners.

At the head of the project is Laura McAtackney who previously conducted a similar project at the Maze prison in Northern Ireland.

Laura McAtackney, a contemporary archaeologist who works at University College Dublin, has conducted a close and systematic survey of the graffiti in Kilmainham. Fresh from a similar project to document the material remains of the Maze/Long Kesh prison in Northern Ireland, where paramilitary prisoners were held during the Northern conflict (1968-1998), she has spent the last six years working on the Kilmainham project. (Check out her blog here).

While there are autographs and graffiti left by such famous figures as Patrick Pearse, Eamon de Valera and Constance Markievicz, her focus, she says, has not been on the ‘big names’ but on the experiences of ‘ordinary prisoners’.

Kilmainham fell into some disrepair after its closure in 1924 but was restored with the aid of volunteers in the 1960s as a monument to the struggle for Irish independence. In latter years the museum and guided tour has also focused on the hundred year history of the Gaol as a punishment for ‘ordinary’ criminals.

Laura McAtackney made the argument that the civil war in particular, in a manner similar to the social history of the Gaol, ran the risk of being forgotten in popular memory. The project to document the Gaol’s graffiti is an admirable way to correct this.