Today in Irish History – July 26th 1914 – The Howth Gun Running

John Dorney on the Howth gun running, which took place 100 years ago today.

On a sunny Sunday in July 1914, the little fishing port at Howth, north of Dublin city, saw one of the most dramatic events in early 20th century Irish history; the Howth gun running, in which a thousand rifles were openly imported to arm the nationalist militia the Irish Volunteers.

The Home Rule Crisis

In the summer of 1914 Ireland was in turmoil over whether Home Rule or self government would be granted to it. In the north the Ulster unionists had formed their own militia, the Ulster Volunteer Force to resist Irish self government. In April they imported over 25,000 rifles and five million rounds of ammunition at Larne.

In June, 60 officers at the British Army garrison on the Curragh threatened to resign their commissions if they were ordered to occupy strategic positions in Ulster in aid of the civil power.

Many previously moderate nationalists were outraged by how the unionists had been allowed to arm and to block a law that had the clear assent of the majority. Kevin O’Shiel a law student in Dublin recalled, ‘our pristine childlike faith in Liberal promises began to dissolve… it was but the old, old game all over again… the effect of the Curragh mutiny was terrific but it was mild compared with that of the Larne gun-running…it violently shook our faith in constitutionalism’.[1]

In 1912-14 both unionists and nationalist in Ireland formed rival militias during the Home Rule crisis. The unionists importation of arms at Larne necessitated a nationalist response.

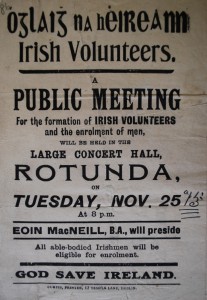

In November 1913 in response to the formation of the UVF, nationalists, openly led by history professor Eoin MacNeill but under the clandestine direction of the Irish Republican Brotherhood or IRB (especially its General Secretary Bulmer Hobson) had formed their own paramilitary force, the Irish Volunteers, to ensure the passage of Home Rule. Against the background of unionist militancy, the Irish Volunteers were popular, attracting 10,000 members by the end of 1913.[2]

According to the IRB organ Irish Freedom, “The young men who stand together…for Gaelic League and Sinn Fein and Republican principles, who are crowding into the Volunteers, can save Ireland and will”.[3] In fact the Volunteers was the perfect mass front for the IRB to infiltrate and control.

In north Dublin, Paul Galligan, a young Cavan man who had joined the IRB three years earlier recalled, “On the formation of the Irish Volunteers in November 1913”, he and his comrades in the IRB, “were instructed to immediately join and take control… Our [IRB] class was distributed over the different units in the city area. I joined at Blackhall Place …Our instructors were ex-British Army men and they were doing the drilling and organisation, but our men of the IRB were really in charge”.[4]

Another IRB man Ernest Blythe in Kerry, similarly got himself made captain of the local Volunteer company, displacing an ex-soldier. [5].

A women’s auxiliary, Cumman na mBan (roughly 1,500 strong) was formed to assist the Volunteers, though some of the most radical women republicans, such as Helen Molony and Constance Marcievicz, elected to join the socialist Citizen Army instead, where they given equal standing with the men.[6] The Volunteers also had a ready made youth wing, the Fianna Eireann, founded by Constance Markievizc in 1903 as a nationalist alternative to the ‘imperialist’ Boy Scouts. The Fianna were in fact to provide many of the most militant Volunteer activists.

Fearing that he would be undermined by the radical nationalists, John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party and the architect of Home Rule, quickly tried to bring the Volunteers under his party’s control and in June 1914, after repeated meetings with Eoin MacNeill and Bulmer Hobson, managed to get himself and his appointees co-opted onto the Council of the Volunteers.

For Tom Clarke and Sean McDermott, the most militant advocates of insurrection among the IRB and the most contemptuous of the Irish Parliamentary Party, this was a despicable betrayal, but in the short term, the endorsement of the Volunteers by the Redmondites merely made the group more popular; its membership soaring to 180,000 by the late summer of 1914.[7]

Without arms though, the Irish Volunteers could be dismissed as a stage army. Irish Freedom editorialised, ‘A dozen rifles are more effective than a thousand resolutions in Parliament’.[8] But as yet the Volunteers had no rifles at all. This all changed in the most dramatic fashion on July 26th, 1914.

Planning to arm the Volunteers

Leading IRB member and later President of Ireland Sean T O’Kelly, in later years recalled that shortly after the organisation had been set up, an armaments sub-committee was formed with a view to procuring weapons. In this they had the co-operation of number of well-heeled Protestant nationalists such as Alice Stopford Greene who donated her house for meetings and Roger Casement the former British diplomat, who, along with longtime separatist Darryll Figgis tried to secure arms in continental Europe. Significantly, O’Kelly recalled that, ‘Probably the Redmond nominees on the National Executive were kept in ignorance of all these military activities’.[9]

The IRB led faction at the heart of the Volunteers was determined to arm the organisation from an early stage, but declined to tell their supposed allies the Irish Parliamentary Party

After futile attempts to buy weapons in France and Belgium, Figgis and Casement finally sourced some 1,500 surplus 1871 vintage Mauser rifles in Germany. They were obsolete single shot weapons but they were real rifles and that was enough for now. It remained however to plan how to get the arms into Ireland and to Volunteer units in Dublin.

The weapons were to be taken from Hamburg by tug boat and then met off the Irish coast by two yachts, one of which the Asgard, manned by among other Erskine Childers and his wife Molly, was to take the weapons into the fishing village of Howth, around 15km north of Dublin city. According to Bulmer Hobson, IRB General Secretary and brains of the Howth operation, the idea was to import the weapons openly to create as big a propaganda sensation as possible and perhaps, to provoke the authorities into counter-productive repression.[10]

O’Kelly recalled frantic meetings in Dublin cellars the week before the landing at Howth. The IRB know the police and possibly the British military too would try to impede the landings and as a result it was decied to issue the Volunteers with oak batons if a riot ensued, and a small number of IRB men with firearms should a confrontation with the Army ensue. Again though, non-IRB Volunteer leaders such as Eoin MacNeill the movement’s founder, let alone the Redmondites, were not informed. [11]

Howth

Bulmer Hobson recalled, ‘About twenty members of the I.R.B. under the command of Cathal Brugha were sent to Howth early on the morning of Sunday, 26th July, with instructions to disport themselves about the harbour, hire boats and generally look as much like tourists as possible. Their business was to receive the yacht, help to moor her, and in the event of any police interference they were sufficiently numerous to deal with it. It was my intention to bring the ammunition away from Howth in taxis and distribute it at several points in the city. [12]

IRB man and Volunteer Paul Galligan’s battalion was mobilised on that day for a route march to the fishing village of Howth, north of Dublin. “Through my IRB contacts, I knew there was something serious on, but did not know exactly what it was”. [13] In fact, they were to march to Howth harbour, to unload from the yacht the Asgard, a cargo of 900 rifles and 30,000 rounds of ammunition.

Paul Galligan watched as the Fianna the nationalist boy-scouts, now acting as the youth wing of the Volunteers, brought up handcarts full of oak batons, which were handed out to selected men. At the quay in Howth, Galligan, “saw a yacht coming into the harbour. She hove-to at a point in the pier and made fast and the crew started handing out rifles to the Volunteers”.[14] A Cumman na mBan activist, remembered that, at the sight of the arms being taken off the Asgard, “we cheered and cheered and cheered and waved anything that we had and cheered again”.[15]

Despite the efforts of the Dublin Metroplotian Police and the Scottish Borderers regiment to prevent it, nearly 1,00 rifles were openly imported at Howth and brought back to Dublin.

Galligan saw the coastguard fire off rockets to warn the authorities, but by that time all the rifles had already been handed out and the battalion was ready to march back to the city. The commissioner of the Dublin Metropolitan Police, Harrell, upon hearing of the arms landing, ordered the police, backed by British troops, to intercept the Volunteers, declaring, “a body of more than 1,000 men armed with rifles marching on Dublin constitutes an unlawful assembly of a most audacious character’, and ordered the police to seize the weapons.[16]

To the rank and file of the DMP, however, most whom were Catholics and probably nationalists of a sort, this seemed like a blatant double standard. The unionists had been allowed to arm but the nationalists were not. Whether because of this, or because they, unarmed, did not want to face down 1,000 armed men, many policemen failed to obey the orders to intercept the return march from Howth.[17]

Those that did often came off the worst in scuffles with the Volunteers. According to Bulmer Hobson, ‘A considerable number of the police did not move and disobeyed the order, while the remainder made a rush for the front Company of the Volunteers and a free fight ensued, in which clubbed rifles and batons were freely used. This fight lasted probably less than a minute, when the police withdrew to the footpath of their own accord and without orders’.[18]

As a result of the police’s unwillingness to act, a battalion of troops – the Scottish Borderers – was called out. Along the Howth Road, on the way back into the city, Galligan’s Volunteer battalion saw that, ‘British soldiers were drawn up across the road with bayonets fixed.’ The soldiers had been ordered to seize the Volunteers’ arms . The two groups of armed men came to a nervous halt close to each other and a Volunteer captain, Judge, went to talk to the British troops. A melee broke out. One Volunteer named Burke who went to Judge’s aid was stabbed with a bayonet in the knee.[19]

Other eyewitnesses recalled that though the Volunteers’ new rifles remained unloaded some shots were exchanged between IRB and Fianna members with revolvers and the troops. One Patrick Egan recalled, that Volunteer officers Eamon Ceannt and Thomas MacDonagh produced Mauser automatic pistols and opened fire on the troops. Also; ‘Lying along the top of a wall bordering the road was a young Fianna lad emptying his revolver over the heads of the men on the roadway into the Scottish Borderers’[20]. The shots must have either been intended as warnings or simply been very inaccurate though, as the soldiers had no casualties.

In the confusion, the Volunteers were ordered to disperse and take their rifles with them. They slipped away across country and through the north Dublin suburbs. Galligan and his club-mates of Kickham’s Gaelic football club made their way to their club house and left the rifles there.[21] Though other companies lost a small number of rifles in similar scuffles, most made their way to various company headquarters.

The day was a triumph for the Volunteers and a humiliation for the authorities. The British had not opposed the landing of Unionist arms at Larne but had now attempted to halt forcibly nationalists doing the same thing. Worse, from the British point of view, they had not succeeded in preventing the importation of the German Mauser rifles. Another batch was brought ashore more secretly the following month at Kilcoole, County Wicklow.

Bachelor’s Walk

And even worse was to come for the British. The Scottish Borderers, who had failed in their mission to disarm the Volunteers, returned to the city to be jeered, (‘go back your own country’ they were told according to newspaper reports) and stoned by a hostile nationalist crowd as they were marching back to Royal Barracks along the Dublin quays. The troops opened fire on the taunting crowd on Bachelor’s Walk, killing three bystanders and injuring 37.[22]

Irish Freedom the IRB newspaper exulted, “The Volunteer Movement has been formally baptised in blood. Proudly and in broad daylight the armed nation has been upheld. The young men are ready to fight for Ireland. Ultimate victory is very close now”.[23]

British troops opened fire on a jeering crowd in Dublin after the Howth gun running killing three people.

They were particularly impressed by the reaction of the policemen of the DMP, a body they had previously excoriated for their role in baton charging both radical nationalists and striking workers. ‘While innumerable acts of brutality can be credited to the DMP, cowardice, individual or collective cannot be alleged’. By their, ‘’manly attitude’ in refusing to disarm the Volunteers, the police, ‘usually instruments of foul anti-Irish work’, ‘may have lit the flame that will paralyse English government in Ireland’.[24]

The crisis over Home Rule really did appear to be growing out of the control of either the British authorities or John Redmond. Two rival militias now existed in the country, both armed, and the forces of the state, both in the Army and the police had, in different ways appeared to show that they could not be relied upon to put them down should the need arise.

Irish separatists thought the events at Howth were the precursor to a popular nationalist uprising but the outbreak of the First World War temporarily defused the crisis.

In fact though, in the short term the dramatic events at Howth and Bachelor’s walk were overshadowed little over a week later by the outbreak of the First World War. The Volunteers split as the Redmondite faction back the British war effort while the militant IRB-influenced minority refused to support it. In the short term it looked as if the Home Rule crisis had been defused by the looming catastrophe unfolding in Europe.

However, within two short years the gun imported at Howth were heard in anger on Dublin streets in the Easter Rising of 1916.

Also listen to the History Show on the Howth Gun Running here.

References

[1] Fearghal McGarry, The Rising, p28, 73

[2] Charles Townshend, Easter 1916, p45.

[3] Irish Freedom, March 1914

[4] Paul Galligan Witness Statement BMH

[5] Ernest Blythe WS BMH

[6] Helena Molony BMH, also Cal McCarthy, Cumann na mBan and the Irish Revolution, p 32-33

[7] Townshend, Easter 1916, p52

[8] Irish Freedom July 1914

[9] Sean T O’Kelly BMH

[10] Bulmer Hobsom BMH

[11] O’Kelly BMH

[12] Bulmer Hobson BMH

[13] Galligan Witness Statement BMH

[14] Ibid.

[15] Townshend, Easter 1916, p56

[1] Ibid. p55

[16] Padraig Yeates, A City in Wartime, p4.

[17] Bulmer Hobson BMH

[18] Galligan BMH

[19] Patrick Egan BMH

[20] Galligan Witness statement

[21] Padraig Yeates, A City in Wartime, p5

[22] Irish Freedom, August 1914

[23] Ibid.