A Report of the Athlone Irish Civil War Conference 23 November 2013

John Dorney reports on the Old Athlone Society’s Conference on the Irish Civil War, held in Custume Barracks Athlone, November 23 1923. Thanks to the main organisers, John Keane and Liam Walsh and to the chair Pat McCarthy of the Military History Society of Ireland. For those unfamiliar with the historical background see The Irish Civil War a Brief Overview.

Entering a military barracks as a civilian, especially as one who spends much of their time studying violent conflict, always has a somewhat surreal feeling. In Custume Barracks, Athlone where this Conference was held, in 1922, the Second in Command of the first Irish garrison, George Adamson, was killed by anti-Treaty IRA fighters months before the official start of the Civil War.

Nearly one thousand anti-Treaty prisoners were interned there in 1922-23. One, Patrick Mulrenan, was shot dead by Tony Lawlor, a National Army officer who apparently decided simply to have a pot shot at the prisoners. Lawlor also tried to have 8 of his own men shot by firing squad, only to be countermanded. Five anti-Treaty prisoners were, however, formally executed there in 1923, in reprisal for which the anti-Treatyites blew up the town waterworks. (Details taken from Ian Keneally’s talk in the conference)

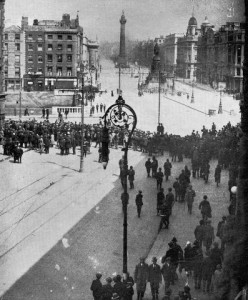

On the cold morning of November 23, 2013, by contrast, all in the barracks was peaceful and orderly as 200 people, including historians, journalists and past and present politicians gathered to learn about and to debate the Irish Civil War, some 90 years after it ended, with a refreshing lack of partisan rancour.

The politics of Civil War history

The Irish Civil War is a classic example of Freud’s ‘Elephant in the corner’, an event that loomed so large in Irish politics and was so upsetting that people preferred for a long time not to speak of it at all.

The Irish Civil War loomed so large in Irish politics and was so upsetting that people preferred for a long time not to speak of it at all. When they did it was generally in acrimonious dispute.

Where the Civil War was debated it often fell into an acrimonious but also predictable debate between partisans of one faction or the other; ‘De Valera sent Michael Collins to London to be a scapegoat’. ‘The Irregulars tried to fight against the will of the People’. ‘The Free Staters executed more Irishmen than the British’. ‘They put the Black and Tans in to green uniforms’, and so on.

Such polemics had an added urgency from the 1970s to the late 1990s as the Irish state was again being challenged by armed republican militants in the Provisional IRA, who in their campaign against Northern Ireland likened the Republic of Ireland to a treacherous pro-British puppet state. For those who disapproved of republican violence, to discredit one challenge to the 26-county state in 1922-23 was also to discredit a current one. For militant republicans, to undermine the legitimacy of the Republic of Ireland (or as they often preferred to call it, ‘the Free State’) as a representative of nationalist Ireland was also to validate the use of ‘armed struggle’ in the present.

History or Propaganda?

John Regan in the keynote address of the conference, illustrated the disturbing extent to which Irish historians let this background influence their interpretations of the Civil War, to the extent that they may even have twisted the facts to suit their argument. He used as an example the much-lamented destruction of the Public Records Office, which housed 1,000 years of Irish historical records, during the battle for the Four Courts in late June and early July 1922.

The Public Records Office had been used as an ammunition dump by the anti-Treaty garrison of the Four Courts and towards the end of the siege, as National Army troops were advancing into the complex, it exploded, badly injuring many soldiers and also destroying documents of state and law in Ireland going back to the Norman conquest in the 12th century. At the time, the pro-Treaty forces alleged that the building had been deliberately destroyed by anti-Treaty timed ‘mines’ which had intended to kill their soldiers. The anti-Treatyites maintained that the explosion had been caused by the Free State forces’ artillery bombardment of the complex.

John Regan showed how later Irish historians such as Tom Garvin, David Fitzpatrick and most recently Dermot Ferriter in his 2009 RTE documentary ‘The Limits of Liberty’ have uncritically accepted the pro-Treaty claim and how some have labelled the act ‘cultural vandalism’ on the part of the anti-Treatyites. The problem, Regan maintained, is that neither they, nor we in 2013, know any better than the people in 1922 who was responsible for the explosion.

John Regan questioned if historians should be so certain in pronouncing on who was responsible for the destruction of the Public Record Office in the Four Courts in 1922.

Certainly the anti-Treaty IRA used mines in the Four Courts complex and used the Public Records Office as store for their ammunition and explosives, but the pro-Treaty troops were shelling the complex and can also be shown to have used incendiary bombs on occasion during the fighting in Dublin (28 June-July 5 1922). Regan’s research also came up with the disconcerting fact that Michael Collins’ government requested poison gas from the British armouries in order to ‘smoke out’ anti-Treaty strongholds (they were, perhaps fortunately, refused).

All of which must lead to the question; why then did historians make such confident assertions about the culpability for the Four Courts explosion and the destruction of the Public Records office? For Regan the answer lies in the partisan disputes over the Northern Ireland conflict. He warned that without proper use of sources history can fall into a type of propaganda.

Green against Green in the midlands

John Burke and Ian Kenneally added contributions on the politics of the Civil War, particularly, in light of the conference’s location, in the midlands region.

At the time and since, the split in Irish republican ranks in 1922 over the Anglo-Irish Treaty has been explained by such motifs as anti-Treaty militarists versus pro-Treaty democrats and conversely unselfish anti-Treaty patriots versus pro-British ‘Free State’ careerists. John Burke’s talk on the Civil War in the midlands brought back into the picture bewildering muddle of events that conspired to cause the Civil War and which tend to make such grand narratives, if not redundant, certainly more awkward to deploy.

The June 1922 election he argued, cannot be regarded as a simple test of support for the Treaty due the Pact between pro and anti-Treaty Sinn Fein candidates. While anti-treaty republicans always maintained this agreement was broken by the Treatyites at the last minute, Burke showed that in some constituencies, such as South Mayo, it was observed and two pro-Treaty and two anti-Treaty candidates were elected unopposed. On top of that 80% of Sinn Fein voters, both pro and anti-Treaty gave their second preference to other Sinn Fein candidates, regardless of where they stood on the Treaty issue. Also complicating the picture is the fact that both the Labour Party and the Farmers’ Party did very well in the election – a Labour candidate topped the poll in Laois/Offaly for instance.

John Burke argued that the ‘Pact’ was not really broken in the midlands in the 1922 election, which makes divining the opinion of the public there on the Treaty more difficult.

Intimidation was certainly present; anti-Treaty IRA leader and TD Dan Breen for instance made personal visits to Farmers Party candidates ‘advising’ them not to run. But pro-Treaty candidates were also, Burke argued, in favour of an uncontested election. Moreover the Provisional government declined to seek the Dail’s approval for commencing military operations against the Four Courts, only recalling the Dáil in September 1922, by which time they had already captured most of the urban centres in the country. Laurence Ginnell TD, the maverick anti-Treatyite TD and the only one to take his seat, was ejected from the Dáil for asking if TDs would be accepted from Northern Ireland.

The August 1923 election that followed the Civil War, Burke showed, saw a substantial increase in support for anti-Treaty candidates – which rose to 27% of the vote in midlands constituencies and higher elsewhere – indicating either that the 1922 election had underestimated their electoral support or that suppression in the Civil War had generated sympathy among voters, a pattern that was seen across the country.

Ian Kenneally detailed the military events in midlands region (as described at the start of this article). As elsewhere it was characterised by initial competition over which side would occupy barracks, followed by the arrival of pro-Treaty forces in strength led by Sean MacEoin, who successfully dominated the region from their base in Athlone. Thereafter the anti-Treaty campaign was reduced to a low level affair with much destruction of property and the occasional assassination. The pro-Treaty forces responded with a few reprisals of their own and seven executions, five in Athlone and two more of apolitical armed robbers in Mullingar.

Keneally also talked about the attitude of the press in Ireland in Ireland, which was he told the conference uniformly pro-Treaty. As a result such newspapers as the Freeman’s Journal and the Irish Independent were the target of repeated attacks by armed anti-Treatyites.

The Military History of the Civil War

The story of the midlands (and many other areas) during the conflict begs the question of why the anti-Treaty IRA, formed from a core of the most battle-hardened guerrillas in the struggle against the British in 1919-21, and initially far more numerous than the pro-Treaty National Army fared so badly in the Civil War. After all despite in July 1922, holding a solid block of territory, complete with the cities of Cork, Limerick and Waterford, by late August 1922 they had been routed out of their fixed positions and some eight months later were brought to complete defeat, with much of their leadership and thousands of fighters imprisoned and the rest reduced to small scale harassing actions.

John Borgonovo attempted to explain why the anti-Treaty IRA could not make the transition from guerrilla units to regular army in the early weeks of the Civil War.

John Borgonovo, whose special interest is County Cork, which was for a brief period the capital of the anti-Treatyites ‘Munster Republic’, attempted to explain their poor military performance.

Borgonovo had a number of compelling explanations for their defeat. Firstly the pro-Treaty side controlled the organs of state and had the means to collect taxes, pay, equip and arm their Army, which, perhaps as little as 4,000 strong at the start of the war, was nearly 60,000 strong by its close –opposing no more than 15,000 anti-Treatyites (in fact Borgonovo argued that there were no more than 1,000 well armed anti-Treaty fighters in its heartland of south Munster in mid 1922).

The Free State was also of course bankrolled and armed by the British government (and occasionally aided by their armed forces as well). A few attempts to tax Cork harbour notwithstanding, the anti-Treaty IRA had no comparable resources of money or weapons.

So far so familiar, but none of this explains the abject failure of the anti-Treaty IRA to wage conventional war in the summer of 1922. However Borgonovo had cogent explanations for this too. Whereas the National Army inherited the IRA GHQ leadership, the anti-Treaty IRA inherited their decentralised guerrilla units in Munster. Operating almost autonomously against the British, this had made them very difficult to eradicate, but in the Civil War made coordination of their units almost impossible.

Ann Mathews talked about women prisoners in the Civil War

Another interesting point Borgonovo touched on was that guerrilla warfare in 1919-21 had made Liam Lynch the IRA chief of Staff, averse to risking heavy losses. This helps to explain the constant stream of retreats he ordered in the summer of 1922, abandoning Cork city, for instance almost without a fight. His logic was that maintaining the IRA’s strength for guerrilla warfare was more important than holding territory; an attitude that would have made sense had the IRA had the popular support and clear political aims necessary to successfully fight a guerrilla campaign against the Free State government.

Borgonovo commented that another shortcoming of the anti-Treaty IRA was their failure to effectively mobilise the women of Cumann na mBan for such tasks as nursing and logistics during the most intense fighting in July and August 1922. In fact though, as the guerrilla campaign went on, republican women did play a central part, as messengers, propagandists and occasionally perhaps even as fighters.

Ann Mathews told the Conference how such women fared after they were imprisoned by the Free State. A total of 645 women were imprisoned – compared to perhaps 14,000 men – and only 375 were held at any one time. Their story is no less fascinating for all that. The women prisoners (who were held at three locations in Dublin Kilmainham Gaol, Mountjoy Gaol and North Dublin Union) included such prominent republican activists as Sheila Humphreys, Mary MacSwiney and Maud Gonne. But not, Mathews told us, Constance Markievicz who fled to Scotland and returned only after the conflict was over.

They also included Dorothy McArdle who later wrote the well-known republican history of the time; ‘The Irish Republic’. However it was interesting to discover that she had not been a republican at all until her arrest during the Civil War. She apparently was merely in the wrong place at the wrong time during a raid on the Cumann na Poblachta party offices on Dublin’s Suffolk Street. Like many others her politics were the fruit of her experiences, not of abstract ideology.

The women prisoners were certainly no less militant than the men, going on hunger strike no less than 24 times. However Mathews argued that they were in fact rather better housed and fed than their male comrades. She also highlighted some interesting class divisions. ‘Political’ women prisoners, often from well educated middle class backgrounds, were given a ‘criminal’ prisoner as an orderly to cook and clean for them. Also, while working class republican women prisoners were simply given a train ticket home on their release, their middle class counterparts were checked into a type of nursing home to recuperate.

‘A Church Militant’

Ann Mathews talked about how collective saying of the rosary was one of the rituals of the anti-Treaty women prisoners and that they even had an ‘OC [officer commanding] prayers’. This highlights the fact the majority of people on both sides of the Irish Civil War were, in the main, practicing Catholics.

The attitude of the Catholic Church was therefore extremely important to the conflict’s result and Patrick Murray told the conference about the stance of the Church during the Civil War.

A commonplace, particularly of republican histories of the period is that the Church had never truly supported the fight for Irish freedom and showed its true colours during the Civil War with its open support for the Free State government.

Murray showed there is some truth in this statement. The Catholic Bishops had urged TDs to vote for the Treaty and formally supported the pro-Treaty side in the Civil War. They denounced and sometimes excommunicated anti-Treatyites and some churches in Kerry even allowed National Army troops to mount machine guns in their steeples (an attitude Murray quipped that that was an extreme example of the ‘Church Militant’).

The Irish Catholic Bishops openly supported the Free State whereas the Vatican urged them to mediate between the warring factions.

On the other hand, he also argued that the attitude of the Catholic Church as a whole was more complex. For one thing, the clergy was divided. According to his research some 60% of priests were vocally pro-Treaty, another 20% vocally anti-Treaty in defiance of the Bishops and 20% more voiced no opinion.

Equally interestingly the Vatican was highly critical of the stance of the Irish Bishops and urged them, instead of supporting one side to the conflict, to mediate a peace deal. The Pope sent an envoy Luzio, to Ireland who reported back to Rome that the republicans were more pious and that government figures in particulars Kevin O’Higgins was, ‘a sinister figure who order executions’. The Irish Bishops did not heed Rome’s instructions but the Vatican did not recognise the Free State until 1929.

The Civil War in perspective

Bill Kissane a political scientist and author of the ground breaking ‘Politics of the Irish Civil War’ attempted to place the Irish internal conflict within a European context.

He argued that, rather than being a uniquely Irish tragedy, the civil war in fact had much in common with events elsewhere in Europe. It was part of range of civil wars and internal conflicts that broke out after the First World War for one thing. Like the contemporaneous conflicts in, for instance, Finland and Ukraine, it was the result of fissuring of an independence struggle into competing factions. And like most civil wars in inter-war Europe (Russia being the one prominent exception) the conservative side won. Todd Andrews also made this connection, comparing, as he saw it, the quashing of the Irish Republic with the suppression of the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

Bill Kissane argued that the 1922-23 conflict was part of a wave of internal wars in Europe that followed the First World War

Ireland in short he argued was not that unique. The only unusual thing about Ireland compared to other conflicts in the wake of the Great War, he argued, was the relatively low death toll (around 1-2,000 compared to 34,000 in Finland for instance). He put this down to the ideological similarity of the two sides, and the absence of straightforward class conflict or ethnic and religious friction that would have raised the stakes involved and opened the way for much more ruthless elimination of enemies than actually occurred.

Finally Kissane argued that the silence that has surrounded the Irish Civil War is also not unique. In Finland it was the 1960s before the 1918-19 civil war could be openly debated.

Gavin Foster (who spoke to the Irish Story about the Civil War here) spoke more about memory and his oral history project which involves speaking to relatives of participants in the Civil War. Unsurprisingly he has found that the overwhelming memory of the Civil War is silence. Children of combatants knew that terrible things had happened that could not be spoken of, but it was a rare family indeed that ever divulged details to their children.

These silences lent the memory of the Civil War something of the air of a neurosis. Richard Mulcahy and Eamon de Valera for instance, surviving leaders of the two rival factions would never speak publicly about the Civil War, but Foster said, their private papers are obsessively full of details of the Treaty split and whose fault it was.

The cliché goes that history is written by the victors, but commemoration is often dominated by the losing side and certainly this is the case with regard to the Irish Civil War. Memorials to the dead, Foster concluded, in a haunting series of photographs of graves, headstones and statues are overwhelmingly for the defeated republican side.

This was an extremely interesting and stimulating Conference. Thanks are due to the Old Athlone Society for organising it. One of the prices of silence on any episode of the past is that it never truly leaves the present. So to conclude, it is only by more open and well researched discussion of the Civil War of 1922-23 that it can finally be consigned to history.