‘Waterford Parted from the Sea’ – The Irish in Newfoundland

Shay Dunphy explores the historical and cultural links between south-east Ireland and Newfoundland in Canada.

The first Europeans arrived on Newfoundland’s shores as early as the 16th century. Basque, Portuguese, French and English fishermen were attracted by the rich supplies of cod to be found off its coast. By the seventeenth century English fishing vessels began to introduce an Irish dimension to the cod fisheries, in the form of servants for the fish trade. Although the Irish influence on the island was limited at first, they would before long leave a cultural stamp on Newfoundland life. One so distinct in fact that historian Tim Pat Coogan in his book on the Irish diaspora “wherever green is worn” opined ‘nowhere in the world outside of Ireland itself, is the Irish presence so strongly felt as in Newfoundland.

One is aware there of Irish resonances on all sides, resonances of music, personality, physiognomy and history”. This is quite a heady claim considering the mantle of most Irish place outside of Ireland has traditionally gone to perhaps Liverpool or Boston. However, the unique history of Newfoundland through its fisheries has meant that ones impression of it, such as its capital St. John’s and the Avalon Peninsula in the south-east of the island is of an overwhelming Irishness. Irish immigration to Newfoundland had been reduced to but a trickle by the time of the great famine exodus to Britain, the United States, mainland Canada, Australia and Argentina. So why then does Newfoundland still retain that peculiarly Irish character it has? The answer lies undoubtedly in the fact that the emigration from Ireland to Newfoundland was very specific.

From Ireland’s south-east to the New World

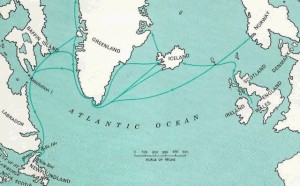

The areas from which these Irish immigrants had come from have recently been mapped with the discovery that they predominantly came from a small region in Ireland. In fact it has been pointed by John Mannion a Galway man and professor of geography in Memorial University, Newfoundland that ‘no other province in Canada or state in the USA drew such an overwhelming proportion of immigrants from so geographically compact an area in Ireland for so prolonged a period of time’.

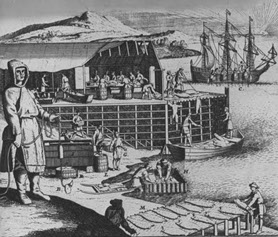

The vast majority of Newfoundland’s immigrants came from specific areas within four bordering counties of south-east Ireland namely south Wexford, south Kilkenny, south-east Tipperary and all of Co. Waterford. From this area of Ireland nearly all of Newfoundland’s Irish descended population traces its roots from. Why then you may ask was Newfoundland the “choice of destination” for emigrants from the south-east corner of Ireland. The answer lies simply in the fact that Waterford city by the late sixteen hundreds became a bustling port, heavily engaged in the provisions trade supplying English ships that called to port for food items such as salt pork and beef.

Waterford port’s success in attracting the provisions trade was aided to a great extent by the rich fertile soils of the region that enveloped it and where local merchants could gain easy access to quality agricultural produce and in turn sell it to the English ship companies bound for the American colonies. However, by the mid-eighteenth century, other ships began to call at Waterford, this time not looking for provisions but instead for local Irishmen keen to work in the Newfoundland fisheries. There were many takers with most of them coming from within walking distance of the city.

Most of the Irish fishermen in Newfoundland were farmers’ sons from the inland areas through which the Suir, Nore and Barrow rivers flowed

The majority of them were farmers’ sons from the inland areas through which the Suir, Nore and Barrow rivers flowed. The ironic aspect of this workforce from Ireland is that many of them had absolutely no experience whatsoever of the sea and that would be a source of constant complaint of British government officials in the Newfoundland fisheries. However, this seemingly insurmountable difficulty still did not deter the droves who crossed the Atlantic to work the summer fishing season. Remarkably this migration was seasonal and many would in fact return in the winter to Waterford with wages from the fish companies or indeed fish itself that could be traded for money in the port.

Such were the trading links then between Waterford and Newfoundland that it was perceived to be close in mind but certainly not geographically. For potential migrants there was no American wake here, not at first anyway as fish workers migrated seasonally in almost the same fashion as the potato pickers or “tatie hokers” of Achill, Erris and west Donegal did to Scotland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The first permanent settlements

After 1780 things began to change however, migrants that once returned to Waterford in the winter after the fishing season ended in Newfoundland became immigrants. Permanent Irish settlements began to spring up on the island and their influence would soon be felt. These settlements expanded greatly in the south-east of Newfoundland, most notably in the Avalon Peninsula region in the late seventeen nineties. This deserted wilderness once traversed by small numbers of native Beothuck Indians who had sadly long since disappeared from the island would by the turn of the nineteenth century have four Catholic parishes complete with resident priests.

Initially the Irishmen came seasonally to Canada but by the 1780s they began to set up permanent settlements.

Despite the fact that Newfoundland’s population at this time was dwarfed by Ireland’s, those Irish who established settlements on the Avalon peninsula had began to shape the island’s character. Many of these settlements were often isolated locations called ‘outports’ which were little fishing coves or harbours with relatively poor access. Essentially they became quasi-Irish colonies completely detached from the influence of British settlers who tended to settle in the northern half of the island.

It is from these areas and the capital city St. John’s that today’s Irish Newfoundlanders are descended from. The aforementioned Professor Mannion has asserted that between 1800 and 1830, over thirty-five thousand people from a region of Ireland with a radius of about fifty miles settled in sparsely populated Newfoundland. In other words what occurred was a sort of south-east of Ireland population transplant across the ocean. A British government official in the capital St. John’s as much as admitted this fact in 1842 when he wrote ‘Newfoundland is merely Waterford parted from the sea’. The south-east Irish brought with them their traditions and customs but perhaps most important that unique strand of Catholicism known as “Irish Catholicism”.

In 1838, construction began on what would be in 1859 the largest church building in north America. The magnificent St. John’s basilica overlooks the capital city and in a sense reflects the dominating influence the Irish continue to exert in Newfoundland. Significantly it was constructed by craftsmen from Ireland’s south-east using materials from Ireland’s south-east. Church architecture has left an indelible Irish mark on the Newfoundland landscape. Religious orders such as the Christian brothers arrived on the island in the early nineteenth century and their buildings are exact replicas of the congregation houses in Ireland. It is perhaps no coincidence that the order’s founder Edmund Rice had been a provisions merchant in Waterford involved in the Newfoundland trade.

Culture and Music

Irish Catholic culture and its specific devotional practices still remains vibrant in Newfoundland but perhaps the most interesting replication of old Irish customs from the homeland can be found in the ‘outports’ of the Avalon peninsula mentioned earlier. To this very day an Irish custom endures in Newfoundland where in the homeland it appears to have largely disappeared. The “Cúairt”, where neighbours traditionally visited each others houses at night to tell stories and play traditional music incredibly still survives there. It has been kept alive by the descendents of the early Irish pioneers whom many of them are as much as six or seven generations removed from Ireland.

A British government official in the capital St. John’s recorded in 1842 that ‘Newfoundland is merely Waterford parted from the sea’.

These rural areas along the Avalon Peninsula remain exclusively Irish and Catholic retaining Irish traditions which have been passed down from generation to generation. Any visitor to Newfoundland however will perhaps be most struck by the island’s accent particularly around the south of the island. It bears such an uncanny resemblance to the Waterford/south-east accent you might be forgiven for thinking you were speaking to someone who’d just got off the passage East to Ballyhack ferry.

Moreover, a quick flick through the telephone directory will perhaps explain why. You’ll find page after page of Brennans, Walshes, Powers, Doyles, Hallahans, Dunphys, Nolans, Murphys and Phelans, surnames you’ll have no difficulty finding in Ireland’s south-east. Despite the fact that the island had been inhabited by native Indians and fishermen from European colonial powers it was the sheer homogeneity of the Irish settlers in that they all came from in and around Waterford that gave the island its Irish sounding accent.

Music is another important cultural aspect of Ireland transplanted to Newfoundland. In rural Irish Newfoundland particularly, life mirrors rural life in the homeland to a great extent. It is centred on the parish where it is not uncommon still to witness so-called “garden parties” which are almost a replica of the ceilí style gatherings found at home. In addition Sean-nós, that distinctive Irish style of singing is particular striking as a cultural transplant from Ireland. The great Irish folklorist from Co. Limerick, Kevin Danaher once noted that “Nowhere in the world is there an area more closely related in its folk tradition to Ireland than Newfoundland”. Intriguingly the Irish influence on Newfoundland music has not entirely come directly from Ireland itself. In the mid to late nineteenth century.

Migration within North America

Newfoundlanders of Irish descent often migrated to the New England coastline of the United States for seasonal work. They were subject to the same discrimination by Americans that the hordes fleeing Ireland’s famine had to face. To contemporary American social commentators – not knowing the fact they had formerly been an ocean apart – the two groups appeared identical which is evidence of how completely intact Irish identity was in Newfoundland. Many of the Newfoundland Irish would settle permanently in New England but many returned north and brought back with them aspects of Irish-American culture through their contact with Irish immigrants. Irish-American ballads are a good example of this and it remains part of the repertoire of Newfoundland folk music to this day.

Irish people are only now really discovering their own immigrant story and with that an increasing awareness of Newfoundland’s historical and still thriving Irish dimension.

Then Irish President McAleese officially recognised the ties of kinship between the two islands when she formally opened a permanent exhibit on the subject at Waterford’s Museum of Treasures. The city’s twinning with St. John also cements the historical and cultural links they share. As the historian Aidan O’Hara has pointed out ‘todays Newfoundlanders take their politics from Canada but spiritually and culturally they remain Irish’.