Arthur MacMurrough Kavanagh -The Limbless Landlord

Brian Igoe looks at the career of an extraordinary 19th century landlord and his times.

Brian Igoe looks at the career of an extraordinary 19th century landlord and his times.

This is a summary of the little known story of Arthur MacMurrough Kavanagh, a 19th century Landlord who was born with no legs or arms, and yet was an expert horseman, a first class shot, a noted yachtsman, an active local Justice of the Peace and administrator, as well as a Member of Parliament. And all this before modern medicine had developed the prosthetic limb. I shall call him Arthur, although in his own day such familiarity from a stranger would have been unthinkable.

Everything published to date on this remarkable man has concentrated on his youth, between the ages of 13 and 22, when he spent his time travelling in the Mediterranean and Egypt, and on a huge tour of Russia, Persia and India. His impact on Ireland though, peripheral as it was, came later, from his 22nd birthday onwards. His life was lived against the background of the Great Famine and the lesser one thirty years later, the Railway boom, the Fenian and Irish Republican Brotherhood activities, and the increasingly vicious confrontation between Landlord and Tenant which followed.

In modern parlance I suppose you would call him “mixed up”. Deeply religious, he nevertheless abhorred the developing strife between Protestant and Catholic; a convinced conservative, he abhorred the changes which would result in the end of “landlordism”; and a genuinely good man, he was born fifty years too late to be appreciated. And he was born with no legs and no arms.

Background.

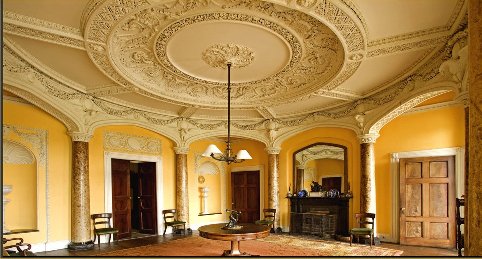

Arthur was born in Borris House, Borris, in County Carlow, on the 25th of March, 1831. In the wider world outside the family home, the Roman Catholic Relief Act three years ago finally allowed Catholics to become Members of Parliament. Most of the other restrictions had already been brought to an end, and now there remained only the Tithe Act, itself due to go in six more years.

Arthur was born in Borris House, Borris, in County Carlow, on the 25th of March, 1831. In the wider world outside the family home, the Roman Catholic Relief Act three years ago finally allowed Catholics to become Members of Parliament. Most of the other restrictions had already been brought to an end, and now there remained only the Tithe Act, itself due to go in six more years.

In spite of his name and his heritage as the heir to the Kings of Leinster making him one of the Five Bloods, the remains of the ancient Irish nobility, he was a Protestant because his father had converted to Protestantism to enable him to be an MP, long before the Relief Act. In fact the distinctions between Protestant and Catholic were far less important in his father’s day than they would become in Arthur’s. There were families like the Butlers, for example, the Earls of Ormonde, who seem to have changed sides, so to speak, on several occasions.

Childhood.

Arthur’s mother, Lady Harriet, was his father’s second wife, married in middle age after the death of his first wife. Lady Harriet was a Protestant and was to have four children, a girl and three boys. Arthur, the baby born on Friday March 1831, was the youngest one. All of them were brought up in the knowledge that they were aristocrats and landlords, and as such had a duty to look after those who were less fortunate. That was the way in which the world was ordered, by God.

Arthur was born with no arms or legs but his mother was determined that he would lead a full life

Arthur was born with no arms, and no legs. Or more precisely, no arms below the lower third of his upper arm, nor legs below mid thigh. And in consequence, no hands and no feet. Had he been born into a small farmer’s family, or a labourer’s, or boot maker’s, he would probably have spent his life perched on the doorstep gazing up and down the street and chatting with sympathetic passersby. But he wasn’t. This baby, so unfortunate in his misshapen body, had had the good fortune to be born into one of the wealthiest families in Ireland.

His mother Lady Harriet, seems to have been a lady of formidable character, although not really tested until Arthur was born. She was no simpering maiden and devoted herself totally to this limbless child. Her elderly husband was uninterested in the little cripple, disinterested even, but she had employed a special nurse to look after Arthur, and to her must go much of the credit for his dogged spirit. Her name was Anne Fleming, and she had a remarkable talent, an insight into the little boy’s mind in all sorts of ways. She would place toys just beyond his reach so that he had to wriggle towards them, ignoring his screams of frustration. She showed him the potential of his short arm stumps, and encouraged him to try to get them to meet across his front.

He could often be seen, even as a baby, lying on his back and trying to get them to meet. He would be given a toy to hold, a big one at first, and as the toys became progressively smaller, so his reach became longer. It made him rather round shouldered, but that was a small price to pay. The tips of his arm stumps became so supple that they could be used almost as fingers, and perform all sorts of tasks. Over the years he was to keep up his painful practice until he could get a tight grip on a cane, a pistol, even the hilt of a fencing foil.

As he grew older and reached the age when a normal child would have walked, Anne arranged for pads for his leg stumps and taught him to balance on them, then hop. Later he would hop from the floor up the stairs, to a sofa or to a chair. When he was two years old, instead of taking him for walks as she would a normal child (and did with the older children), she arranged for a small pony with a built up saddle, rather like a small bucket, into which he was strapped. Anne was to stay for years, and Arthur became very attached to her.

When he was about four years old, a new influence came into his life, and a most important one it was too – Doctor Francis Boxwell. A recently qualified young gentleman, he came from a landed family at Butlerstown in County Wexford, and was very much at home with the Kavanaghs at Borris. He was an old family friend, and in 1835 when he arrived, his qualification papers from Glasgow University were only weeks old.

He developed an instant rapport with young Arthur, and indeed with his mother. He visited almost daily, and with keen intelligence realised how important it was to be consistently friendly, but firm. He lectured Lady Harriet on the vital necessity that Arthur should be instinctively self-sufficient if he was to have any hope in life, and how he must be proud of his family heritage – how he must be, limbs or no, a man.

Horse-riding developed in him a sense of independence

Riding a horse came as naturally to Doctor Boxwell as breathing, and one of his first actions was to replace the leading reins on Arthur’s pony with real ones. This he managed by having a harness made for Arthur’s torso with straps and buckles, and the reins were attached to these. He also redesigned the bucket in which he sat, turning it more into a sort of saddle chair, and indeed one of them can still be seen in Borris House today. So equipped, by turning his shoulders or pressing down on one or both reins with a stump or stumps as required, he could turn a horse or stop him as well as anyone.

It was a brainwave, and combined with the new saddle into which Arthur was firmly strapped, it gave him immense and hitherto undreamed of mobility. Arthur had a natural affinity for horses, perhaps increased by his dependence on them. He would talk to them, and they with a soft whinny would sometimes talk to him, too. And this applied not just to his own stable. Often abroad, forced to ride half trained animals over often precipitous passes he would encourage them just by talking to them in his deep, mellow tones, sympathising with their difficulties and sometimes even with their terrors.

Schooldays at home were quite common for youngsters in Arthur’s place in the world at that time. Grand houses often contained a schoolroom where the children of the family were taught by a resident tutor or Governess, and where they dined – formally – with that same august individual presiding at the head of the table. In Arthur’s case there were obvious difficulties. Holding his book, for example. After various experiments they found that the best solution was for his book to be hung round his neck, he turning the pages with his lips. To write, he sometimes held the end of the pen in his mouth, and guided the nib with the tips of his arm-stumps.

The Adult.

By 25th March 1853, his 22nd birthday, his father and two elder brothers had died, and so quite unexpectedly he was Squire of Borris. However it was a Borris beset by creditors. And debtors, but they were mostly penniless tenants. The Great Famine had been hard on them, though nowhere near as hard as in the west of Ireland, but all the same rents had fallen sadly behind.

In the aftermath of the Great Famine in the 1850s Arthur took over his father’s estate at Borris

Many landlords were simply evicting defaulting tenants, and as often as not ploughing up their smallholdings and planting grain. Before the famine there had been nearly eight million people in Ireland. Many of the lucky but now landless tenants, some two million of them, had emigrated to England or America. The unlucky, at least one and a half million, just died by the roadside. But to evict starving tenants had never been an option for the Kavanaghs. Instead they had fed them.

Arthur realised that work was needed urgently. Money was short, but much could be done without money. In India he had learned draftsmanship, and there was timber a-plenty at Borris. What was needed was a sawmill and the other necessaries of building – bricks, mortar, slates. So he designed the houses himself (and won a prize from the Royal Dublin Society for the best designed houses at the lowest cost) and he erected a sawmill. He must have charmed the funds for the building materials and perhaps the mill itself from friends, for within a short time a transformation was taking place, and the village of Borris much as we see it today was being born.

Marriage.

Next, he married. At 21, his bride, Frances (whom he always called Fuz) was three years younger than himself, and their union seemed to be that rare thing in upper class society in Ireland in the 19th century, a love match, happily coinciding with the wishes of both sets of parents! Frances must have had some reservations, however, about the possibility that their offspring might suffer from Arthur’s problems. There is a story that, before his marriage, he drove his fiancée around the neighbourhood of Borris and pointed out several fine children of his own as a proof that their offspring were not likely to be deformed!

Arthur lived a full life, and knew he must give, as well as take. At Christmas he gave more than advice, he gave presents, usually a parcel of meat and another of clothes, blankets and the like, and for those who lived in a distant part of the estate or in the hills, he would often tie the parcels to his saddle bow and deliver them. In very harsh winters he didn’t wait for Christmas. He enjoyed giving to those in need, and he once wrote that he was “sending portions to them for whom nothing was prepared.”

The allusion presumably was the Lord’s table which for him had been prepared so abundantly. It seems to have been old fashioned altruism mixed with religion, for he was a deeply and genuinely religious man even if he cared little for the distinctions of Catholic and Protestant. Much of the overriding preoccupation with religious distinctions which so characterised Ireland was a novelty for Arthur, a legacy of the Great Famine, and it clearly irritated him. A nationalist named Thomas Davis had written a piece of doggerel at in the 1840’s which might well have come to mind.

What matters that at different shrines

We pray unto one God?

What matters that at different times

Our fathers won this sod?

In fortune and in name we’re bound

By stronger links than steel;

And neither can be safe nor sound

But in each other’s weal.

The thinking behind the verse was very much to his taste, but that one God, he knew, had preordained every man his place in Society, and had done since time began. Landlords were just as much part of the fabric of the country as were the peasants. Without the Landlords, the peasants would still live in mud hovels and scratch a living from the earth. And by an accident of history when the King had wanted a divorce three hundred years before, the vast majority of Landlords were now Protestant.

Local matters.

He was already fully occupied on his own lands, in his saw mill, sitting on the Bench as a JP, and now he spread his wings and got involved in Railways. The first railway had come to Ireland when Arthur was three years old, so they were nothing new. Over the last ten years, railways were spreading to Carlow and Kilkenny with the building of The Great Southern and Western Railway. The first line was from Dublin to Cashel and then on to Cork, which it had reached seven years earlier when Arthur was in Russia. But it had grown since then. Carlow station was now connected to both Waterford and Dublin, while the nearest point of railway line to Borris was at Bagnalstown, on the way to Carlow.

McMurrough Kavanagh donated land to the railway company if the railway ran through Borris

So Arthur donated land to the railway company if the railway ran through Borris. The idea was for the railway to go from Bagenalstown, more or less due south (through Borris of course) towards New Ross until it was past the Leinster hills. A spur would go to New Ross, while the main line turned eastwards to Wexford. The railway was designed by William le Fanu, a noted Dublin engineer who was working on the main Cork line, and was grandly named the B&WR for “Bagenalstown and Wexford Railway”.

And increasingly his interest in local government seems to have developed. He had been appointed High Sherriff of Kilkenny a year earlier, but had regarded it as more of an honour due to his position than as any sort of obligation. High Sheriffs were only appointed for one year, so when Arthur’s year at Kilkenny expired he accepted the appointment of High Sheriff of Carlow, and now took it more seriously.

The High Sheriff was the representative of the Queen, and wholly independent of the Government. Moreover, it was fast becoming part of a sort of modern day cursus honorum, the target being a seat in the House of Commons and perhaps higher honours. The next step in the cursus was the Poorhouse – it’s management, that is. In the same year as the Carlow appointment he accepted a seat on the Board of Guardians of the New Ross Poorhouse, or Workhouse as it was sometimes called. So passed Arthur’s twenties. And he was aware of it. In his diary on March 24th 1861. he wrote,

“This is my last of the twenties; to-morrow (D.V.) the thirties begin. What a ten years to review! When I began them, a homeless wanderer in India; what mercies I have had showered upon me! Have I tried to use and not abuse them? Have I cared for the people committed to my charge? Have I tried to make myself useful, and duly to fill the position in which I have been placed? Hard questions to answer. I have tried: but have I looked to God to help me, to give me patience, to encourage me when I have been weary and disgusted, to make me thankful for what I had, and not longing for things I had not?”

Politics

By 1866 Confrontation between Landlord and Tenant, between Protestant and Catholic, now seemed no longer merely possible, but probable. So when, in November, the Member for Wexford, a well known and much respected Dublin barrister named John George, had to resign having been appointed a Judge of the Irish Court of the Queen’s Bench, Arthur contested for, and won the seat, with a majority 759.

The election was noted as far away as Australia, where the Brisbane Courier of January 18th 1867 noted “On Monday, Mr. Arthur Kavanagh was elected member for Wexford county, beating Mr. Pope Hennessy, the young Tory Catholic barrister, who used to be the link between the Conservatives and the Pope’s brass band, by a large majority.

Mr. Kavanagh is descended from an ancient Irish family, and has a good patrimony, but it was his misfortune to be born without feet or hands-indeed he has but very short stumps in the place of either of his four limbs. He has a handsome face and robust body, with what is still more to the purpose, he has a quick and powerful mind, which has enabled him in a most wonderful manner to triumph over his sad physical disadvantages. He writes beautifully with his pen in his mouth, he is a good shot, a fair draftsman, and a dashing huntsman. He sits on horseback in a kind of saddle basket, and rides with great fearlessness. He lately wrote and published a lively and smart book called “The Cruise of the Eva.” He has married a lady of beauty, and has a large family of handsome children. He is about forty years of age, exceedingly popular in all the country round, and has now been elected a member of Parliament by the acclaim of his neighbours. He will make a sensation in the House of Commons; but how much better this than the doings of the Irish over the water. In New York they have just returned one John Morissey to Congress, a ruffianly gambler and blackleg, who has been in prison repeatedly – a convict, punished for all manner of offences.”

Getting to and from Parliament was a great deal of trouble for most Irish MP’s, and one would have thought that for Arthur it would be even more so, his railway line notwithstanding. The usual way would have been to take a train to Cork, and from there take the steamer to Bristol, whence it was 5 hours by train to London, although increasingly as the railways developed people were going by Kingstown (Dun Laoghaire) and Holyhead.

As a Conservative MP, Arthur travelled to London in his own private yacht which he moored under the Houses of Parliament

Arthur however usually combined his love of sailing with the business of Parliament by sailing there in his own yacht, which (exercising a long disused privilege) he then moored under the Houses of Parliament for as long as he remained. He would be rowed to the Speaker’s Steps, whence he went in his wheel chair to the Members’ Lobby, then was carried by his servant into the Chamber by a side entrance behind the Speaker’s Chair and not easily seen. He would be placed in his chair, where, covered with his fashionable and voluminous cloak and wearing his top hat there was little visible to distinguish him from other members, while by special dispensation his servant remained beside him. Only when it came to a vote was there a problem, and then the tellers would come to him.

Arthur’s initial exposure to Parliament came at a time of flux. When he arrived at the beginning of 1867, rebellion was in the air in Ireland. The Fenians or Irish Republican Brotherhood were becoming active but at this stage rather inefficient. “The Manchester Martyrs” were martyred. An American arms shipment to the rebels went back to America because nobody met the ship. An attempted gaol break using explosives, in Clerkenwell London, did so much damage and killed so many local residents that it merely achieved a huge increase in the strain between the Irish in London and the locals. And finally the Fenians found themselves opposed by the Church, the Roman Catholic Church, which was a major setback. Terminal, in the short term anyhow.

Dublin’s Archbishop Paul Cullen was passionately devoted to the concept of freedom for Ireland, but equally passionately, he was a man of peace. He felt, and strongly asserted, that the aims and ambitions of all the Irish could best be achieved by negotiation. He had long since condemned the activities of the Young Irelanders, and he was now highly alarmed at the activities of the Fenians and the IRB, which were overtly violent. So much so, in fact, that he was moved to recommend to the Pope their excommunication, and in due course that deed was done.

Land Reform and Disestablishment.

Typical of most of Arthur’s speeches in the House was that he never talked about things he knew nothing of. When he spoke, it tended to be on local, Irish, issues, on Landlords good and bad, their rights and their duties, or on things to do with the sea. Then in 1868 a General Election resulted in a Liberal victory, and so the very Conservative Arthur found himself in opposition for the first time. Ireland, which returned a majority of Liberal members, 65 seats to the Conservatives 40, because the Irish vote was strongly influenced by the twin issues of land and disestablishment, on both of which the liberal Gladstone had promised reform if elected.

Arthur believed passionately, as had his ancestors before him back to King Dermot MacMurrough and beyond, in the right, the Divine Right he might have said, of Landlords to their position in Society. But equally he believed in the obligation of Landlords to look after their Tenants, the Tenantry in the phrase of the day, in sickness and in health. It was a very paternalistic outlook, but it had worked well.

Arthur believed in the rights of landlords but also in their obligations to their tenants – a paternalistic attitude that came uder attack in the Land War of the 1870s and 80s

And Arthur did his level best to emphasise, again and again and again, the obligations of the Landlords. Immediately after the ‒ lost ‒ election, he had voted with the Conservatives against the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland ‒ he had been elected as a Conservative and had always deplored the religious strife in Ireland so cared too little to make a stand of any sort. But here was something he did care about, the Poor Laws in Ireland, and he knew about them. So now for the first time he felt moved to make his view known. The paper reported it thus:

“ When the House had been for some two hours listening rather lazily to the familiar and combative utterances of some three or four representatives from Ireland, one of the latter sat down, after delivering himself upon Union chargeability, and half a dozen other Irish members started to their legs, straining their necks to catch the eye of Mr. Speaker. But the right hon. gentleman in the chair, quietly nodding towards the Opposition benches said,

‘Mr. Kavanagh.’

“ The effect of the words was electrical, and in an instant every eye in the House was turned towards the back seat, almost under the gallery, where the hon. member for Carlow sat, cool and collected, his papers arranged before him on his hat, and his face turned towards the chair.

Opening his views in clear, well-chosen language, the hon. gentleman dived into his subject, and, in the course of a speech of some twelve minutes’ duration, exhibited an intimate knowledge of the question under discussion which, as an extensive Irish landowner, he would naturally possess, placing before the House his own experiences of the working of the Poor Law electoral system, and taking this comprehensive view of the Bill before the House : that it was only a fractional part of that larger and more important question which the Government should deal with, viz. national taxation.

To his remarks the Speaker and the Premier [Mr. Gladstone], especially the latter, paid great attention, and as the hon. member took off the upper sheet of his notes of reference from his hat and applied himself to the next slip, encouraging cheers came from every part of the House.

At the conclusion of his speech Mr. Kavanagh was loudly cheered. Judging by the matter of his first address, and the manner in which it was received, it may reasonably be predicted that Mr. Kavanagh, who belongs constitutionally to that type of men which wins in public life, the men with the large heads, deep chests, and faces full of force, will be often heard with advantage in the House of Commons.“

Shortly after, a teller delivered to him a note from the Speaker:

DEAR SIR

I offer you my compliments on the excellent manner and tone of your speech, which, as you will see, has made a very favourable impression on the House.

Yours sincerely,

J. E. DENISON.

But he also spoke for legislation protecting tenants. Again and again. For example speaking on the Irish Land Bill the following year, he took up the cudgels against Disraeli. To quote from Hansard:

MR.KAVANAGH said, he could not support the Amendment of the right hon. Member for Buckinghamshire (Mr. Disraeli), for he considered that having not only voted for the second reading of this Bill, but having openly accepted the principle that a deterrent penalty should be imposed upon capricious evictions, by giving a tenant a right with certain provisoes to claim compensation for disturbance, he could not now stultify himself by supporting an Amendment which directly negatived that principle.

But he was bound to say that Her Majesty’s Government had sorely tested his consistency. As the clause now stood un-amended it was unjustly harsh, the scale of compensation unwarrantably high; but when he looked at the Amendments placed upon the Table by the Chief Secretary for Ireland, he found that he proposed to make it harsher still. The simple plea of protection to the tenant would seem to be abandoned, and that of hostility and injustice to the landlord openly avowed. If this was the sort of spirit in which the Government were going to deal with this Land Bill in Committee, he would, he thought, not only be warranted in supporting the Amendment now before them, but of using every means in his power directly, and indirectly, to defeat the measure.

However, dim as it might seem, he would still cling to the hope that the Government wished to do justice between man and man; that they, and the great party opposite by whom they were supported, would still apply to the details of this measure the tests of equity and reason.

The next years saw the pressure for change in Ireland growing, and before long it would become irresistible. An Irish barrister named Isaac Butt. MP for Youghal, had founded the Irish Home Government Association. Before long this Home Rule League as it had been renamed took 59 seats and became overnight a force to be reckoned with. Parnell now appeared on the scene, and a horrified Arthur had to watch him take over the Home Rulers where Isaac Butt had left off. For Parnell was an Irish Landlord.

Confrontation and defeat.

By 1877 all that was some years in the past when the potato crop in the west failed again. For three years in succession. So the associated evil of evictions began again, too. There were 1,238 evictions in 1879 and 2,110 in 1880, and these had resulted in 863 and 2,950 ‘incidents’ in the same periods. The damage had been done, and throughout Ireland Landlord and Tenant were firmly established on the road to confrontation. And Arthur, well meaning though he was, was like all of us a child of his background. In a sad speech about his own record Arthur commented; “For twenty-two years I have occupied the position of an Irish landlord and for ten years out of that period I have been my own agent over the largest part of my property. I have spent considerably over £20,000 in helping tenants to improve their holdings, to roof their dwelling houses and offices, for which I charge no interest.

During that time I have not had more than six cases of ejectment on title—that is, for other causes than non-payment of rent—and in those cases for non-payment of rent, there has seldom been less than three years’ rent, with no prospect of the tenant ever being able to pay anything, had I left him in his holding. This statement applies to a rental comprising over 1,200 holdings, with a small average rent of not £14 per holding.”

But they were very much the minority, these good landlords, and anyhow it didn’t really matter now, because landlords were being attacked not because of their individual failings, but because they represented Landlordism. The people were restless, starving and restless, and starvation made them desperate.

This was the beginning of what history would call “the Land War”, and it was to last, on and off, for twenty years. It was fuelled by the fact that now everyone could read, thanks to the National Schools, and to do it in English. Charles Bianconi’s car network supplementing the new trains meant that newspapers reached every corner of Ireland, every day, and radical new newspapers like the Freeman’s Journal were among them. Confrontation was no longer a possibility, it was a fact, and an increasingly bloody one.

In 1880, Arthur, now the leader of the Irish Tories, lost his seat in Parliament.

The next General Election was called for April 1880. By now Arthur was being described as the Leader of the Irish Tories. But not for long. The result in Ireland was a predictable walkover for the Liberals. For Arthur, it was a disaster, for he lost his seat. More than a disaster, he saw it as a personal disgrace, for as he put it “the majority of my own men broke their promises to me…. the sting that rankles is the treachery and deceit of my own men, my own familiar friends in whom I trusted but that feeling must be choked.”

The election was lost and won, and, in recognition of his extraordinary personal courage perhaps as much as anything else, Arthur was appointed Lord Lieutenant of County Carlow, and was invited to sit on the Bessborough Commission. Gladstone paid him a remarkable compliment in the House, saying “He is one of the ablest, if not the ablest, gentlemen coming from Ireland among the party opposite. Besides his ability he is a man of independent mind, and I do not scruple to call him – making allowances for his starting point – a man of liberal and enlightened feelings”. Arthur, surprised, wrote to Gladstone thanking him for the compliment, one “which I never expected and it is on that account more valued”. Gladstone, in sending his thanks for the note, said his opinion was ”not of recent formation.”

The Bessborough Commission had been appointed to inquire into the working of the Landlord and Tenant Acts with a view to improving the relations between landlord and tenant. There were five members altogether, including the Chairman Frederick Ponsonby, Earl of Bessborough, hence the name. The members of the Commission travelled all over Ireland collecting their evidence, and finally sat to consider it in 1881 in a hotel in Galway. Whatever the motives of the others, the Commission concluded that tenant farmers were exploited, and it supported the Land League’s demands for “the three Fs” – Fair rent, Free sale and Fixity of tenure. It was a majority decision, with one unsurprising dissenting vote, Arthur’s.

“I cannot agree in the draft report submitted by the Chairman, as I dissent from some of its propositions and the manner in which they are presented. I have therefore endeavoured to draw out a short statement of my views upon the evidence we have heard, as a more satisfactory mode of proceeding than by attempting to move amendments to those portions of their report with which I do not agree” he wrote, and then proceeded to write another 7,600 or so words. All, it must not be forgotten, written by himself, in longhand. Without hands.

His thrust was to propose an extension of the so called “Bright Clauses” of the 1870 Act which allowed tenants to borrow from the government two-thirds of the cost of buying their holding, at 5% interest repayable over 35 years, provided the landlord was willing to sell. It didn’t work, the resulting Land Act, and it’s objective was not achieved until after Gladstone’s fall from power and his opponent Lord Salisbury’s surprising The Purchase of Land (Ireland) Act 1885, also known as the Ashbourne Act was passed. That set up a five million pound sterling fund, worth about $830 million today, and any tenant who wanted to buy land, had access to these funds. They took a loan from the government and could pay it back in monthly instalments at 4% per annum over 48 years. Anyone could now buy land, if the owner wished to sell it.

The End.

Arthur was no longer in Parliament of course, so merely followed events. The Catholic tenants were now forming a new prosperous rural population which Arthur seems to have neither recognised nor understood, and Irish politics had become polarised between Protestant Unionism and Catholic Nationalism. No longer did that mantra “What matters that at different shrines We pray unto one God?”apply. It now seemed to matter very much. His fears expressed in that diary entry so long ago, “worse than all, the curse of this wretched country — Bigotry — displaying itself at every turn, and from every side; everyone convinced that everyone else wants to convert the whole community to his plan of going to heaven or — elsewhere” were being bloodily realised. He was asked to join the Privy Council of Ireland by Salisbury’s new Government in 1886, which must have pleased him. It was a great honour and entitled him to be called “the Right Honourable”. Although it had little remaining power, he would have thought it an indication of approval for his ideas from quarters he valued.

But then he developed diabetes and became seriously ill. And as autumn faded into winter Arthur developed pneumonia and his health began to deteriorate further. He stayed mostly in his London house at this time, now in the new Tedworth Square in Chelsea, perhaps because of the better medical attention there, but it was a losing battle. He kept his diary up, though. He had a good night notwithstanding the Liquorice powder. Then Felt much better on being told by his doctor that his chest pains were indigestion. On November 12th he went to his Club (and was weighed, 6 stone and a few ounces, down from 7 stone 5 lbs in March. Then a last entry, on December 4th, simply Lord de Vesci called.

On Christmas morning that year Arthur asked that Christmas music be sung round his bed where he could hear it better. There, quietly, listening to the singing, Arthur MacMurrough Kavanagh slipped away, exactly three months short of his 58th birthday. It was December 25th, 1889.

Principal Sources:

(In alphabetical order).

- Born without Limbs: A biography of achievement, by Kenneth Kavanagh.

- Familia 1999, The Incredible Mr. Kavanagh. Peter Froggatt & Norman Nevin.

- Hansard (hansard.millbanksystems.com).

- Ireland Under Coercion (2nd ed.) (2 of 2) (1888) / Hurlbert, William Henry, 1827-1895.

- Newspapers, including the Cork Examiner (1856), The New Zealand Tablet (1882), New York Times (1891).

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Seventy Years of Irish Life by W R Le Fanu.

- Stories and sketches by Grace Greenwood.

- The cruise of the R.Y.S. Eva by Arthur Kavanagh.

- The House of Commons, 1790-1820 By R. G. Thorne.

- The Incredible Mr Kavanagh: A Triumph of the Human Spirit, by Donald McCormick.

- The Parnell Commission, Sir Charles Russell, QC.

- The Peerage.com.

- The Right Honourable Arthur MacMurrough Kavanagh by Sarah L. Steele.

- Various articles by the historian and author Turtle Bunberry.