Paul Henry in Achill

![lroy6798[1]](https://www.theirishstory.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/lroy67981-300x227.jpg)

Patricia Byrne looks at the links between artist Paul Henry, Achill, John Millington Synge, Jack Yeats and Sean O’Faolain.

‘The Bog Road’, an Achill landscape by Belfast-born artist Paul Henry (1876-1958), was recently sold at auction for €72,000 having been rediscovered earlier in the year at a BBC Antiques Roadshow. The sale happened a full century after Henry and his wife, Grace, travelled to Achill in the summer of 1910 on a Midland Great Western Railway train. They had come for a holiday on the advice of their London friends, Robert Lynd and Sylvia Duhurst, who had earlier honeymooned there. Paul Henry was immediately captivated by Achill and famously tore up his return ticket to London on a rocky point at Gubalennaun. The couple stayed on the island on and off for the next nine years and the experience fed Paul Henry’s art for almost three decades.

On their arrival at Achill Sound the couple travelled ten miles north by low car to the village of Dugort, where The Colony – a proselytizing Achill Mission settlement – had been established in the mid-nineteenth century. The dark stone of St Thomas’ Church opposite The Colony might well have reminded them both of their early religious upbringing: Grace’s father was a Church of Scotland Minister and Paul’s an evangelical preacher in Belfast. Paul’s maternal grandfather, Thomas Berry, had been a preacher in Achill some seventy years before the artist first visited.

The Henrys were not impressed with Dugort, which seemed to them to be teeming with tourists and where every second house was a hostelry. Tourism to Achill had indeed been boosted by the opening of the railway line to Achill Sound in 1895. Dugort was the principal visitor destination with its beaches, mountains and hotel accommodation at The Colony. Paul Henry’s seeming aversion to tourism at this point is interesting given that, in later years, his west-of-Ireland landscapes would be strongly associated with tourism promotion e.g. his 1920s posters for the London Midland & Scottish Railway.

They pair left Dugort and headed by jaunting car for Keel where they boarded with the Barrett family at the Post Office. The island area between Keel and Dooagh, taking in Pollagh and Gubalennaun, became their focal point in Achill. For Grace Henry, also an artist, a notable feature of her paintings in this period is that many are of nocturnal scenes. She could be seen in her white smock on the old bridge at Dooagh in the early evening, working with the assistance of artificial orange lighting.

Henry’s autobiography, An Irish Portrait (1951), is largely about his Achill experiences. In an Introduction to the book, Sean O’Faolain provocatively wrote: ‘Very few painters have written books and few of these are satisfying.’ Henry accompanied the writer around Ireland in the winter of 1939 and provided the illustrations for O’Faolain’s, Irish Journey.

Henry admitted in Irish Portrait to a fascination with writing and trying to find the right words to convey the emotions he felt. The painter was deeply influenced by John Millington Synge whom he had met casually during his stay in Paris (1898-1900) and he read Riders to the Sea over and over. Henry came to Achill the year after Synge’s premature death and there are parallels with Synge’s own journeys to the Aran Islands in the 1890s.

In his autobiography, Henry tells of hearing that Synge had written a great deal of The Playboy of the Western World in Ballycroy, Erris. Synge had visited the north-west corner of Mayo briefly in 1904, and again in the summer of 1905 with Jack Yeats while on a Manchester Guardian commission to complete a series of articles on the Congested Districts. Synge’s manuscripts reveal that during these trips he was making notes and jottings for The Playboy, which he decided to locate in North Mayo. Paul Henry had his own associations with The Congested Districts Board – and indeed would follow Synge into the Mullet Peninsula, North Mayo – when, for a period during 1917-1918, he was employed as paymaster for the Board. This allowed him the opportunity to travel more widely around the Erris district and other parts of North Mayo.

Another area the artist visited soon after coming to Achill was the island of Inishkea South, where he observed blood-spattered men at work in the Norwegian Whale Fishery and where the boat crew had ‘a grand old time with poteen’. His journey back with a drunken crew allied to the stench of rotting whale on his clothes made the trip a memorable one.

Even if Henry was not impressed with Dugort on first arriving in Achill, he did return to the area to visit the Deserted Village on the slopes of Slievemore. At Booley, where the islanders took their cattle for pasture in the summer, the Deserted Village impressed the artist with its stillness: ‘I was excited and entranced with this glimpse into a world hundreds of years old … it was the ancestral home of the tribe.’ Henry’s response to the scene was not unlike that of the German writer, Heinrich Böll, when he came upon the same spot in the 1950s and wrote of ‘the skeleton of a village, cruelly distinct in its structure’.

In August 1919, partly due to Grace’s need for more comfort and society than Achill could provide, the Henrys moved to Dublin. The period in Achill had put a strain on their relationship and the couple separated soon afterwards. Achill was a crucial influence on Paul Henry’s career, which was recently summarised in the Dictionary of Irish Biography: ‘Ireland’s first painter of peasants, and perhaps the most influential landscapist in twentieth-century Ireland, a naturalist and romantic at heart, Paul Henry painted the west of Ireland landscape in every mood and colouring, and captured its essence.’

~~~~~~

About The Author

Patricia Byrne is a Limerick writer and holds an MA in Writing from NUI Galway. She writes poetry, fiction and nonfiction and her poetry collection, Unstable Time, was published in 2009. She was a featured reader at the recent CUISLE Limerick City International Poetry Festival. Patricia’s literary and historical essays have appeared in New Hibernia Review (USA), The Journal (Australia), Verbal Magazine (Northern Ireland), Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society and other publications. Her essay, ‘Rose and Purple Colours on the Sea: John Millington Synge in Mayo (1904-1905)’, is featured in the current issue of Cathair Na Mart – Journal of the Westport Historical Society. Patricia has presented at the Heinrich Böll Seminar in Achill and at the Writer Conference in Bangor, Wales, and has broadcast on RTE Lyric FM, BBC Northern Ireland and BBC Scotland. She is currently writing a book about the 1894 atrocity at the Valley House, Achill, involving the infamous James Lynchehaun who was one of the influences on J M Synge in writing The Playboy of the Western World. She was a prize-winner in the Unbound Press Opening Chapters Competition (UK) earlier this year. Patricia’s blog is at www.patriciabyrnewrites.com .

Patricia Byrne is a Limerick writer and holds an MA in Writing from NUI Galway. She writes poetry, fiction and nonfiction and her poetry collection, Unstable Time, was published in 2009. She was a featured reader at the recent CUISLE Limerick City International Poetry Festival. Patricia’s literary and historical essays have appeared in New Hibernia Review (USA), The Journal (Australia), Verbal Magazine (Northern Ireland), Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society and other publications. Her essay, ‘Rose and Purple Colours on the Sea: John Millington Synge in Mayo (1904-1905)’, is featured in the current issue of Cathair Na Mart – Journal of the Westport Historical Society. Patricia has presented at the Heinrich Böll Seminar in Achill and at the Writer Conference in Bangor, Wales, and has broadcast on RTE Lyric FM, BBC Northern Ireland and BBC Scotland. She is currently writing a book about the 1894 atrocity at the Valley House, Achill, involving the infamous James Lynchehaun who was one of the influences on J M Synge in writing The Playboy of the Western World. She was a prize-winner in the Unbound Press Opening Chapters Competition (UK) earlier this year. Patricia’s blog is at www.patriciabyrnewrites.com .

~~~~~~

Image Credits:

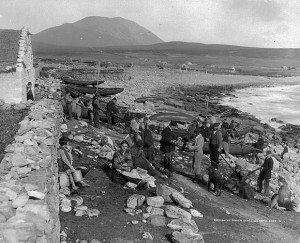

Slievemore Hotel, Achill c 1890. Photo by permission of National Library of Ireland.

Village of Dooagh, Achill c 1890. Photo by permission of National Library of Ireland.